I’ve been obsessed lately with the following question:

Why is it so “hard” for some teams to learn and try relatively basic patterns? Am I biased? Am I missing something? What is difficult?

We’re all a little biased (I certainly am), but…

First Example: Work In Progress/Process Limits and Pull Systems

Limiting work in progress is “easy”. You just do it. Only work on N things at once. Start the next thing only after finishing something (a pull system).

Describing why WIP constraints “work” is also easy. It takes less than 60 minutes to explain, and there are plenty of group exercises (and math, and books, and case studies) that prove the point. What makes limiting WIP “hard” is that doing so will trigger lots difficult conversations — both before you try it, and once you hit the limit and have to figure out how to respond. To understand WIP limits and pull systems, you may also have to challenge your own ingrained instincts:

- What will we do if people are idle? Shouldn’t we keep them busy

- What will we do about our “blocked” items? What if swarming is uncomfortable?

- What if we can get more work done at once? Shouldn’t we try?

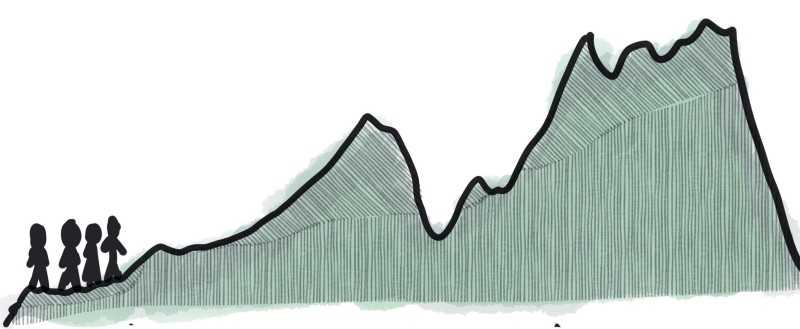

- How can we plan unless teams/individuals commit to doing a batch of work ahead of time? To top things off, the benefits of WIP constraints and pull don’t show themselves immediately. Initially, things will get harder. Whereas before you generally worked around impediments and constraints and eked out work (or tried valiantly to have “successful” sprints)…now, you’ll have to deal with the elephants. And while you do, the peanut gallery — those outside the team — will wonder what the hell is going on. Very tough.

The Challenge

OK. Hopefully you get the idea. I’d argue that many of the things we tackle in software product development aren’t inherently difficult to learn, understand, and “try out”. The challenges are 1) opportunities to practice, 2) our own “legacy” perspective and experiences, 3) temporary discomfort (the “dip”), and 4) a needing a safe and supportive environment. Companies that tackle those things win.

Second Example: User Stories and Thin Slices

Here’s another example. As a relatively experienced “product person”, I have an easy time with writing user stories and decomposing user goals into thin, releasable increments. To me…It isn’t “hard”. I argue that technical practices are “hard”, and that the product stuff is easy. But I frequently hear from developer-types (and the folks that coach them) that writing user stories, and splitting/dividing/shrinking those stories into small releasable increments, is “hard”. And the challenge doesn’t stop with developers…it is hard for less experienced PMs as well.

Of course I’m biased, so I asked experienced coach Allen Holub (check out his site and Twitter) for his take:

I think it’s hard for two reasons. First, the devs aren’t used to thinking that way. They’re thinking in terms of tasks, things they have to build. Second, most devs have little or no contact with actual end users. Some companies don’t have that problem (most of the Spotify programmers use Spotify), but I’ve witnessed situations where one of the devs actually used a company’s product, and nobody would pay any attention to her experiences at all. Everything was delegated to the “product” group, and they were not interested in input from inside the org. More to the point, the company as a whole didn’t really get the notion of user input (and this is, unfortunately, commonplace). People convinced themselves that they knew more about what the users wanted than the actual users, so they never bothered to ask.So that makes sense to me, and also explains my bias…

First, I’ve had a lot of practice taking the user’s perspective…even for product’s that I haven’t (or can’t) “use”. Second, I have a lot of practice (and experience) running and observing usability testing. So I have a sense of where things tend to go wrong, and how users respond to limited functionality. Third, I know my limits! I’m not the user, so it is important to invite the users into the conversation. Fourth, it is easy for me to not get bogged down thinking about implementation…the “things [I] have to build”. So I don’t have to carry that baggage. Finally…I have faith in the “big picture”. I know in my heart that a tiny release moves us forward. We’ll learn something, often backtrack, but keep improving. I do not get stressed like many less experienced PMs.

Yes, experience matters. I have practice (and lots of major screw-ups). But consider all the things that orgs do that inadvertently prevent teams from getting the practice…

Keep busy! No you can’t call the customer directly. No time to attend usability tests! Don’t interact with customers…that is somebody else’s job! UX figures things out in a vacuum! “Product Owner” … fill up that backlog! We need “better requirements” from Product. Maximize velocity! Build exactly this to help close this deal. Hit those estimates. Crank out those features…no time for research. Don’t go slower…or we will not release this sprint! We just need to execute! “Product Owner” … give status updates to fifteen stakeholders before you call that customer! Oh that feature? Who knows if it worked. Well, you know developers can’t empathize…Um, no, I don’t know know that. I vehemently disagree with that.

But you hear this kind of stuff often. It’s no wonder that “story splitting” is hard. No one gets to practice. And I dare say “beginner” teams are kid-gloved and bogged down doing Scrum-by-the-book without really focusing on the basics.

Now contrast that with a team getting full access to a customer, maybe some temporary coaching, and the full permission of the organization to learn and occasionally fail. What if they didn’t need to worry about “business as usual”? What if they could aggressively limit scope — to the point of people having a lot of slack — until they could get in the flow of things?

I’ll tell you one thing…because of the practice and repetition they would learn a good deal faster than I did. I stumbled through a number of work situations without those things.

In short order there would be enough positive reinforcement (happy customers and progress) to validate the approach. I’ve seen this with multiple teams whereby developers (and Product Managers) weren’t thrown into “business as usual” and the organization put a premium on learning. Some number of months later…you had autonomous, self-organizing, and effective teams. Years later you had absolute powerhouses that could deliver complete business outcomes.

In other settings … 5 years, 125 sprints later. Nothing different.

Conclusion

I’m not denying that skills matter, and that some skills have prerequisites. Rather I am arguing that what we call “hard” is often indicative of fear, lack of safety, lack of support, and limited ability to practice. I hear certain coaches frequently talk about things being “good training wheels for low maturity teams” and “newbs”…and then I ask about time spent with customers, slack, letting teams back off of business as usual, and…crickets. Digging in I’ll hear about gnarly org blockers, general org dysfunction, and a lot of unreasonable pressures on the team.

So what is being modeled to the team looks NOTHING LIKE a high-performing team. It isn’t a scaled down version of what works, a safe version, a push-bike. It is an example of what not to do. And then you’ll hear highly saddening things like “our team isn’t smart enough to work in that way” or “the teams aren’t mature enough to get that.”

We are awash in helpful patterns, patterns to learn patterns, patterns to pick patterns, and patterns to make it safe for, and support, patterns. So access to the “right way” or a “better way” is not really the problem (for the majority of us not living at the absolute bleeding edge of a domain, and especially considering that we work with skilled problem solvers). The trick is:

- Create opportunities for frequent practice (not always business as usual). Practice “it”…not a watered down, process filled version of “it”.

- Safety to fail and learn.

- A supportive environment to get us through the temporary discomfort. It may not be as hard as we think. Or put another way … it is always hard, but we should do ourselves every favor possible.