AKA: Seduced By Economies of Scale…

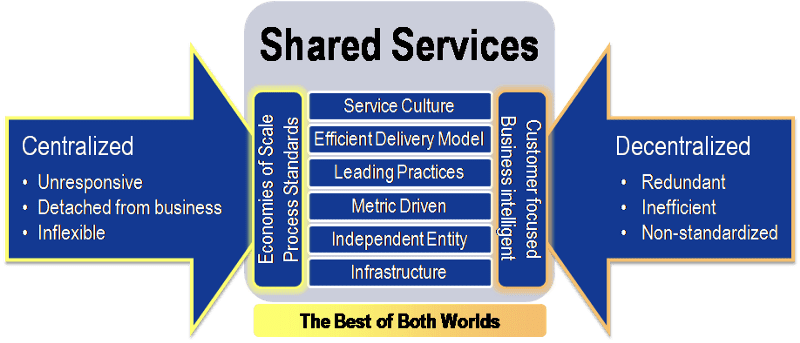

What’s not to like? It’s the BEST OF BOTH WORLDS!

Insert random sell-piece here …First a definition:

A shared service is a capability that is centralized within an organization or group. The capability is wrapped in a service with a well defined service contract with the expectation that all teams use the service unless they can justify a reason to go their own way. Shared services are a common operational strategy designed to reduce costs by eliminating repetition of effort. By providing a service in one place, there is an opportunity to optimize and standardize it at scale. (source)Some pondering and tips (with a bias towards software oriented shared services and product managers):

- Why shared service? Is the working model delivering the expected value to the business, internal customers, and end-customers? The decision to move something to a shared service is based on many assumptions. It’s important to regularly re-validate those assumptions. You can get ten stakeholders in a room who “agree” the shared service is a valuable idea, but disagree about why it is valuable, and disagree about whether it is living up to that promise. We often assume it’s the only way, and that’s rarely the case. The interesting thing is that shared services are a Nested How. We assume we’ll deliver more end-customer value by leveraging:

— Consistency and control, centralized business logic

— Interoperability and standards

— Safety and risk prevention

— Distributed specialization

— Requires cross-concern visibility/access

— Cost savings. Economies of scale

— Accelerate growth. Jump-start or kick-start initiatives

So … what outcomes are you expecting? Where’s the data? Is the shared service working? Is that end-customer value and business value materializing? - What’s working? How do we amplify that? Too often, shared services are based on some vague forecast of economies of scale, some Excel voodoo, a team making a power grab, or a resourcing constraint amid rapid growth. What’s missing are clear and focused wins to amplify. Start with something that works before trying to solve a problem with the org-chart. Stick to the simple question: “is it working right now?” Can we amplify what’s working? Validate something works BEFORE shifting the org-chart.

- Product Traps! Shared services can fall victim to all of the traps that plague external products: the platform trap, premature optimization, going too broad, unvalidated complexity, accumulating technical debt too quickly, faulty business models, etc. We tend to forget this because the market is “internal”, but the rules all still apply. Something can be great for end-customers, but terrible for the provider. Or vice versa. Validate product / market fit early and often. Beware the Franken-Service that wouldn’t last a day in the “real world” as a product. It probably won’t be viable in the long term internally either.

- Seductive Assumptions. When you find yourself confidently saying “we should only solve IT once”, remember that you need to understand that ITs are rarely as simple as they seem. Five different types of customers using IT represent five potential paths for the shared service. The IT needs to eventually deliver end-customer value.

- Divergent solutions are a way to avoid premature optimization, and to keep your options open. The divergent solution approach may be preferable, as long as you can converge when you need to. Oftentimes, you see a bias for shared services because the organization lacks the ability to converge when it needs to.

- Internal Medicine. While susceptible to all of the standard product traps, shared services have some unique gotchas. It can be hard to say “No” to internal customers. You can’t fire internal customers. There are pressures to be responsive and pragmatic in the face of unrealistic demands. You often don’t get to pick your “ideal customer”, or shape your roadmap for long term viability over short-term gains. Lastly, even if your work can be directly linked to revenue, it can be hard to break out of the “less is more” / operating cost bucket. Startups are hard. Startups inside of companies — with internal teams as customers — are harder.

- Consulting-to-product is a viable startup model. But it is a hard thing to pull off. You have to be super disciplined and incorporate the learnings from each consulting “job” into a viable product. Consulting-to-product is very common for shared services, which is funny because it is literally one of the hardest things to get right in the “real world”. This would be fine if the assumptions surrounding a shared service didn’t rely on some massive economy of scale (likely unachievable in a consulting model). When someone talks about a “consultative” focus … step wisely.

- Cash on Delivery. Do your internal customers leave with the work-product in hand? Or do you maintain the product for them? Internal teams have a nasty habit of doing things that would absolutely destroy a startup. If each successive project adds complexity to “the product”, then you’ll need enough person-power to keep that added complexity at bay. Which means you’ll need a funding model built on the continuous delivery of capabilities instead of the completion of individual projects.

- Take A Ticket. Watch out for working agreements that bias you to premature convergence around solutions. This is a hallmark of the “take a ticket” or auctioneer approach. Instead of focusing on the value side — the outcomes we’d like to create — there’s a tendency to slip into a prescriptive feature assembly line. Startups have the same challenge when they attempt to auction off their roadmaps to new customers. The end result is feature-soup and a nonlinear (non-economically-viable) increase in complexity.

- Refactor. As a shared service, are you doing custom and/or experimental work? Are the requirements 100% known from now until eternity? Here’s the trouble … as a shared service you absorb all of the risks for doing custom/experimental work and delivering incremental value, and none of the reward. When stuff goes wrong, and you need to do a big refactor, where are the resources? Worse yet, you get blamed for not being clairvoyant. Be very diligent about communicating risks and forging time for refactoring.

- Autonomy Hit. Shared services make so much sense. Economies of scale FTW. But we rarely take into account the hit on autonomy for all involved. Dedicated resources leveraging a narrow shared service with smaller scope can outperform a “take a ticket” / heavy-dependency shared service 5:1. Once someone / somewhere feels there’s a chance in hell of getting away with fewer resources, it can be hard to change their mind … even when it’s obvious that something isn’t working. Be ruthless about exposing the hit on autonomy. Always ask “can you deliver the desired consistency without centralized control?” Resist the temptation to install rigid control structures when the same outcome can be achieved with a less heavy hand.

- The “generic platform trap” is as real for shared services as it is for startups. Customers will do magical things with your extensible set of tools! As with startups, this is a big, big assumption. Startups end up having to prop up professional services teams to “teach” people how to use the platform, and to develop case studies and white-papers that demonstrate validated solutions to real-world business problems. Or, they get stuck trying to serve too many personas. My advice: solve actual problems. Resist the platform trap. Worry about platform-izing later.

- Don’t be the boiled frog. Lead time starts to slip. Maintenance overhead increases. Internal customers stop having confidence in your work. Things aren’t terrible, but they aren’t at their best. This drift into failure can go on for a long time before you hit a wall. Don’t let this happen. Pivot early. Like any business there is a chance that the shared service simply isn’t viable. Don’t beat a dead horse. It is tempting to see failure in shared services as an individual failure, or a planning failure. But sometimes the business model for the shared service is simply not viable.

- Real Value (Not Proxies). Link your shared service to capabilities and core business metrics … not proxy metrics. Otherwise you will be forever viewed as an operating expense, with all the headcount gymnastics that entails. Capabilities always require care, attention, and iteration. If you assume a project factory approach (aka “take a ticket and wait” or “the auctioneer”), you run the risk of letting the capabilities falter. Get funded based on value delivered. You must tie in your work to end-customer / end-user value. All too often, shared services trigger forms of local optimization. Up go the defenses and the rigid boundaries. Again, the challenge becomes making the org chart work, instead of delivering value. Flip the script … value, value, value.

- Learn the responsible “No”. Sure the customer may be someone you interact with frequently. They might even be your friend. But for the health of the overall product, sometimes you need to say “No”.

Where does your shared service fit on the following ?

There’s no right or wrong here, but this list might be helpful for further teasing out assumptions …

- Emergent vs. mandated

- Pushed to customers vs. pulled by customers

- Reduces local variability vs. facilitates local variability

- Transactional vs. integrated

- Shared service and customer retain autonomy vs. teams are highly dependent

- Scale with minimal cost increases vs. scale with linear cost increases

- Distributed ownership vs. centralized ownership

- Custom product vs. commodity product

- Broad service offering vs. narrow service offering

- Touches end-users vs. far from end-users

- Linked to revenue vs. viewed as operating expense