Today I found myself writing a list to a friend caught in a difficult transition at their company. I like lists, so of course I took it way too far.

None of these are terribly groundbreaking or profound, but I find myself needing an occasional reminder. As a recovering professional canary-in-a-coal mine, I’ve made every mistake in the book.

- All organizations have problems. Healthy organizations have fewer chronic issues, and heal injuries more quickly. Issues seem to work themselves out…eventually.

- Continuous improvement is hard work, even in healthy organizations. Fixing chronic issues is extremely hard work.

- Adding skilled people to an unhealthy situation does not automatically fix the situation. It frequently makes it worse. The skillsets that let people thrive in dysfunctional situations may not translate to health situations. And vice versa.

- Healthy organizations are better equipped to level up promising (but less experienced) people. A common refrain in organizations is that “we can’t find any experienced people”. What they are really saying is that they don’t have the bandwidth to nurture potential.

- Paradoxically, an organization that can respond nimbly (and decisively) to threats is able to spend less time “future proofing” and optimizing for future threats. That said, healthy companies do take proactive steps to foster long-term resilience, even when it doesn’t “make sense” in the short term (e.g. keeping technical debt under control, or rotating teams to areas of unfamiliar code).

- It is tempting to blame the people who were “on watch” as a problem intensified. Keep in mind that many of those people tried to raise the flag. Still others did their best, but unknowingly contributed to the problem due to lack of information/feedback.

- We invest more energy in things when we have some ownership over the proposed solution. The perfect solution foisted from “on high” will underperform the homegrown solution that people feel invested in.

- When talking amongst themselves, consultants will say that your organization’s problems are not unique. They’ll also admit that this perspective isn’t the best narrative for securing work. Then they’ll explain why they stopped working full-time. Keep this in mind when hiring consultants.

- Short term results are not necessarily a good indicator of long-term viability and health. Results in one problem domain, are not necessarily a good predictor of success in another problem domain. Extremely successful companies can be poorly equipped to tackle new challenges.

- Successful (in the long-term sense) companies are able to make risky side bets without fear of damaging their meat-and-potatoes business. Most of these efforts will fail.

- When it comes to understanding our successes, we underestimate the impact of luck. When it comes to grappling with our failures, we overestimate the impact of luck.

- There are always trade offs. High autonomy and flexibility on the local level, tends to come with coordination challenges on the global level. Similarly, an organization optimized to handle large cross-functional projects will likely be less capable of handling small local projects. High performing leadership teams exhibit skill, thoughtfulness, flexibility, discipline, and transparency when it comes to dealing with those trade offs. Cultural manifestos are hollow without action.

- Some % of the organization is buying time until a convenient (and economically advantageous) exit. How this manifests will vary by individual. Individual contributors, for example, may benefit from a quick exit. Executives may benefit from a longer tenure to preserve a positive narrative.

- You are not the only person who “sees the problem”. It is tempting to stereotype people as either 1) “change adverse, and OK with the status quo”, or 2) like you…open and willing to change (obviously!). Things aren’t that black and white. Some people are extremely strategic about when and where they make their bets. Others try the shotgun blast approach. When in doubt, talk to someone with a long tenure to understand the big picture.

- We all want to do our best work. When outside factors make that difficult, our natural response is to fight. It is easy, therefore, to equate our personal needs with that of the organization (e.g. “why aren’t we being more innovative” instead of “I desire more innovative and challenging work, and I don’t want to quit this job yet.”) Try focusing on your needs instead of making everything about the “whole organization”.

- Be on the lookout for widespread recurring back-channel conversations (aka gripe sessions) that don’t seem to lead anywhere. If these persist for more than a couple months, you can be reasonably confident that there’s a stubborn, systemic issue afoot, and that “common sense” alone will not fix the issue. Proceed with caution to safeguard your emotional investment.

- You can boil many issues back to the relationships between key executives. Trust and safety issues trickle down to the rest of the company. The tempting solution is to remove those executives (or add buffers and go-betweens). More interesting is ask how to make the system more resilient against small pockets of toxicity, so that the issue does not happen again.

- Much of the fate of an organization is sealed by a handful of key early decisions (e.g. market positioning, funding strategy, early product decisions, etc.) These decisions are so deeply baked into the context, that they can be easy to underestimate, and difficult to identify.

- Similarly, much of the fate of an organization is linked to key promises: to investors, to senior leaders, to the board, etc. These promises are rarely documented, and rarely shared with the whole organization.

- Organizations are frequently structured around the strengths and weaknesses of key executives/leaders (e.g. a layer of VPs hired with explicit task of “managing” the CEO). The obvious problem here is that when the context changes, and people leave, you’re left with a structure that is not fit-for-purpose.

- New ways of working involve a new vocabulary. It can take months/years (and a great deal of repetition) to develop a functional level of shared understanding. This requires hard work. The temptation is to either 1) try to build before you get going (hard), or 2) just start, and hope things will work out. Neither seems to work all that well. Plan for regular inspection and adaptation.

- Situational awareness and the skills necessary to respond to changes in the environment are not always linked. It is also possible to be extremely skilled at something, but neither situationally aware or capable of change. Balanced teams have craft, sensemaking abilities, the ability to respond, and leverage/support.

- Front-liners are rightfully skeptical of change initiatives. They (often correctly) assume the these initiatives will 1) fail to account for realities “on the ground”, 2) leave them cleaning up the mess, and 3) fail to address systemic issues — especially those related to leadership and middle management. To make change stick, you’ll need to fight that justified skepticism.

- Leaders routinely underestimate the “ripple effect” when initiating change. A small adjustment can have wide-reaching impacts. The front-line routinely underestimates the complexity of global change. A seemingly small, common-sense adjustment, can be very complex to implement across the breadth of an organization.

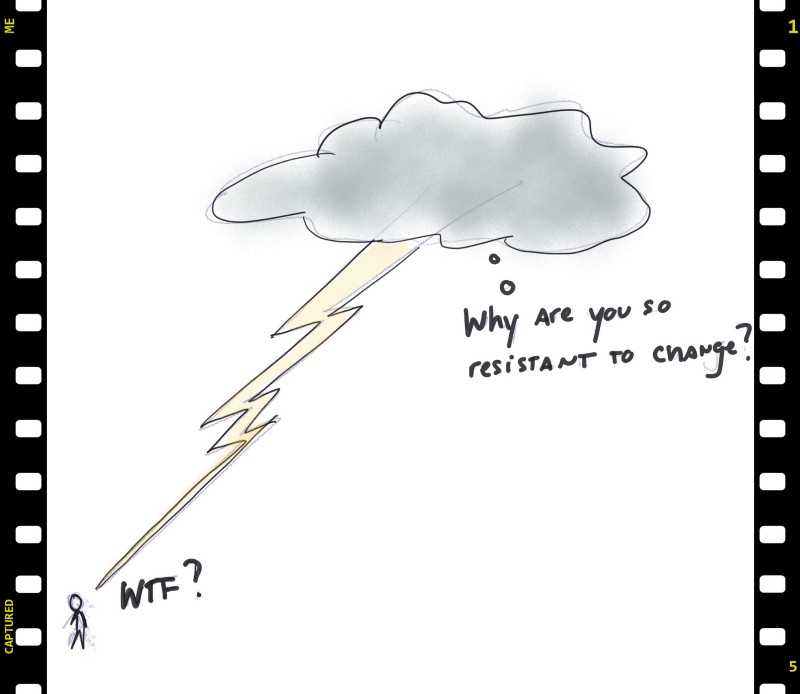

- Many change efforts will fail, especially if they are ambitious and address important problems. Punishing those failures triggers fear, and a resistance to change.

- Fixing the root cause may not fix “the problem”, as the symptoms (and the relationships between those symptoms) may have become a far more deleterious problem than the original cause.

- We are wired to find something/someone to blame. More difficult is accepting that 1) we ourselves are partially (or wholly) to blame, and 2) it may be impossible to single out one factor to blame.

- “Business as usual” has an incredible amount of inertia — enough to crush any well-meaning effort that contradicts business as usual, or is run in parallel to (and not part of) business as usual.

- What appears to be stagnation from the outside, is likely a stalemate of multiple leader-championed change initiatives.

- Insulating teams from dysfunction and distraction (aka “shit umbrella”) may render those team highly effective. But it does not erase the dysfunction. If that layer fails (the dam breaches), or you forced to add another layer of hierarchy, the teams (or new managers) will be swamped.