Here are fifty short product lessons.

I put these together by transcribing brief talks, so the tone is conversational. Apologize in advance for my ability to run on.

I hope you find them helpful.

Table of Contents

- Bets

- Opportunities vs. Interventions

- Danger of premature convergence

- Mission vs. Projects

- Starting Together

- Coherence and the messy middle

- Multiple operating models at once

- Data as a trust proxy

- Chronic vs. Acute Issues

- The pull of short-term thinking (chronic vs. acute)

- The time it takes to get good

- Less Tetris Playing

- Moving fast and slow

- Storytelling, repeated stories

- Strategy as it relates to beliefs

- Prioritizing Opportunities

- Learning Cadence

- Learned helplessness

- Data snacking vs. integrated approach

- Functional feature factories

- Left to right factory lines

- Modeling the business

- Teams closer to customers

- Weird Practices

- One Pagers

- Not dividing out customer facing and non customer facing

- Leaving time to iterate (next)

- PMs creating an environment … good decisions / quickly

- Two priority levels …

- Bring me solutions (not problems) and My Idea-ism

- Safe places to workshop ideas/bets

- The critical moment of realizing intuition needs testing

- Credibility by not manufacturing certainty with your team

- Artificial deadlines

- Forcing functions are valuable

- Not hiding dependencies (and dependency wrangling)

- Products and features are temporary

- Shifts that necessitate this all

- Expertise as a service (vs. ticket takers)

- Perspectives on roadmapping

- Measurement to inform decisions

- The reflection is what counts

- Shared understanding / vocabulary is super hard

- Prioritization spreadsheets

- A longer term view of customers…LTV, a behavioral cohorts

- Product strategy part 2 - don’t outsource it

- Connected / Embedded design

Bets

One interesting thing about bets is that they come in all different sizes. You can have big bets, small bets, safe bets, or risky bets. There is also an element of time: bets can have different durations. You can have really, really short bets that might be short, but still very large. And you can have really long-evolving bets that might take a very long time to mature. At any given time, a company will have a portfolio of bets developing in parallel that are all interlinked and related in some way.

You might ask, “Why is it important to think in terms of bets?” The simplistic answer is, “We’re making an investment, and we want a really good return on that investment.” That is true, but the usefulness of thinking in terms of bets is that the different types of bets, the shape of bets, and the relatedness of bets are very pertinent to product development. There are helpful mental models for what we’re doing.

Some bets take a long time to mature. A startup might be based on one, two or three core fundamental ideas. Although you want to update your beliefs as you start to accumulate data, some things just take a while to mature. It takes you time to understand what’s actually going on. That’s a really good example of how thinking about those fundamental aspects of your company and making those very clear to the people you’re working with can both inspire them to help you update your prior understanding—what information you have relating to those bets—but also help you to communicate the real direction. A classic problem when someone joins a startup is that they come in and appraise what’s going on and say, “Why do we believe that? It seems a little risky. Should we challenge that idea? Should we challenged that other idea?” Often, what they don’t realize is that people have gone through that particular thought process and have decided where to make operating assumptions and have decided if these are bets that they want to play. They’ve decided what they know to be risky and what they know to be safe for this case.

When you can communicate those bets and beliefs to someone who is just joining the company, you save them the hassle of not understanding the thought process of the people who founded the company. The other important thing when you think in terms of bets—as anyone who plays games of skill that involve betting knows—is that there are better ways to place your bets. There are often better ways to play those games. If we have an opportunity to create a game where we can bet more incrementally instead of a big batch bet, of course we’re going to try to create an environment where that is possible.

Some things don’t work like that. Sometimes we don’t have that opportunity, but if we at least understand the game and the bets we’re making, it challenges us to think about the potential for changing how we play that particular game. Another key benefit is that it’s tempting to try to take a one-size-fits-all approach to all the work we’re doing. And just when we try to think about the various bets that we make in our lives or in other areas, we realize that there’s an almost infinite number of variations of these styles of bets.

Yes, they can be sorted into a few categories. and there are some models that encourage you to think about certain categories of bets for your company. But it really makes you aware that you need an adaptive approach to working on these things, otherwise you’re going to try to treat everything in the exact same way. Underscoring this idea of the interrelatedness of your bets and their circumstances is that you can have core beliefs that then filter all the way up into the work that’s happening right now. You can have bets across one to three decades, or a series of bets and beliefs that impact the work that you’re doing right now. That interrelatedness is extremely important to consider.

Opportunities vs. Interventions

One challenge with dividing things into problems versus solutions is something that anyone who has worked in product development understands: almost every problem is a nested solution to a higher-level problem. For example, when I have issues with how we’re going to generate revenue for the company, that’s a problem. But it’s also a solution to some other higher-level mission for the company about why you exist, the change that you hope to engender, or how you want to create long-term growth and value for your company. Similarly, a low-level issue could involve improving the performance of a particular page. That’s also a problem, and it’s a perfectly compelling and interesting problem, but it’s actually a solution for some higher level goal that you’re pursuing.

The challenge is that organizations often struggle to define who owns problems and who owns solutions. The debate will never be resolved completely because at its heart, it’s a debate over how things are decomposed. It’s a debate over who decides how those things are all linked together. One test I use to tease out a problem’s full connection to what’s going on within the company is to imagine some really smart person in the back of the room continually asking, “Why,” or “What are we hoping to achieve with this?”

Now, opportunities and interventions are a little different, because the word intervention implies that we’re somehow doing something that may change behavior for our benefit or that may actually change behavior in a way that we didn’t expect—or which might not even be beneficial for the company.

And it implies a temporary nature to our efforts. It implies that we might decide not to continue intervening that way. It’s a useful framing for how people think about delivering features. They imagine a level of permanence to what they’re doing, that it’s going to stick around forever and that they need to perfect what they’re putting out there in the world. That kind of pressure on what you’re doing causes a lot of problems.

Similarly, with any product, there is guaranteed to be a steady stream of problems to solve, but just because a problem exists (or just because customers are complaining about something), this doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s value in solving that problem.

You also expose this by framing things as opportunities. For example, we have an opportunity to make customers more successful at something, or we have an opportunity to unlock this part of the market. Yes, you could also frame that as a “problem.” However, this lens reveals that there’s not really one underlying binary problem that is either solved or isn’t solved.

Perhaps you’ve have or haven’t successfully realized opportunities or explored a certain area. We learn more about the opportunity as we dig into it. You can incrementally capture value from a particular opportunity. Those are characteristics of problems that are hard to talk about. And things will also pop up that don’t strike anyone as a genuine problem.

Let’s take a not uncommon example: a status quo exists, and people are generally happy with how things are. You could look at this and think there’s not really much you can do there. Now, opportunities imply that there may be ways shift the paradigm from how you’re currently working.

Thinking about prioritizing problems to solve, it actually feels a little different to when you’re prioritizing opportunities to capture additional value. This perspective tends to inspire people to think a little bit more broadly about what they’re doing and can actually inspire people to be a little bit more strategic about what they’re doing. Framing situations in terms of opportunities and interventions can go a really long way in terms of getting your team to be more impact-focused.

Danger of premature convergence

So what is premature convergence? Premature convergence is trying to zero in on a solution (or decision) earlier rather than later, potentially too early. Now, this can obviously be a little tough to judge. There’s an ideal spot that that’s probably a range for most of your efforts. But the really important thing is that our intuition often drives us to converge on a solution earlier than would be optimal. This happens because we don’t like uncertainty. We want plans, we want to be able to say exactly what we’re going to do.

Uncertainty is often not highly regarded in a company environment. People are rewarded for having a very specific plan and being able to say specifically what they’re going to do. The other temptation is that people want to keep a team really busy, or they want to make sure that there’s something teed up ready for the team to jump into next. There’s pressure on them to formulate those plans and lock down what those plans are earlier rather than later.

All the reasons why you want to converge earlier are very clear, but all the costs of doing that are often not very visible. So unless you’ve actually experienced it and experienced the benefits of waiting to converge—or of allowing a period of messy reality—it’s unlikely that you’re going to really see the net benefit.

Often, when you converge later, you realize you’re solving the wrong problem. You have an opportunity to gather diverse perspectives, you get more people seeing the problem for the first time and experiencing the problem for the first time. This is difficult when you just drop things on a team out of the blue. They don’t have that experience of grappling with the problem for the first time. They might not think about creative ways of solving that particular issue. And the people who have the idea are often subject to a lot of confirmation bias and sunk cost bias. They’ve invested a lot of time in coming up with that particular solution or converging on that particular problem. Now, even though we know this, it comes up again and again and again, and it’s tough to even call it an antipattern because there’s so many near-term reasons why we think it’s right to do that, that it’s almost an intuition trap.

So when is the right time to converge? It’s easy for me to say, but I think the answer is “a little later than is comfortable.” This idea is borne out as you look at a cross-section of teams. When you’re converging at the right time, there is a period of messiness, there is a period that includes a little bit of discomfort. This is how you know you’re on the right track. When you’ve converged a little too early, what you’ll typically observe is near-term speed and efficiency by jumping into the problem, a kind of near-term momentum. But often just a very short amount of time into the effort, it really becomes clear. Maybe you started off on the wrong track, or it’s very hard for people to communicate all the requisite contexts that they have because they converged early. You’ll experience a big hiccup. That’s one way of recognizing that you’ve converged a little too early: look for that initial sense of certainty. It’s usually a pretty good sign of what’s happening.

One additional thing to be on the lookout for is that when things are moving slowly, there’s often a heavy, heavy urge to figure out all of this stuff upstream. This is particularly strong when people are twiddling their thumbs because there’s not a lot of flow in the system. People tend to converge more and more on plans. You should resist these impulses; the whole idea is to plan at the last responsible moment instead of planning instinctively because you’re so nervous that things aren’t happening right now.

Mission vs. Projects

There have been a couple really amazing talks recently about product thinking versus project thinking, and I think that those discussions are extremely valuable. It’s very important to understand the difference between what a project is and what a product is. But I don’t actually think the comparison is apples to apples. It’s a challenge in the sense that when you are iterating on or offering a product, there tend to be initiatives or missions baked into doing that. You could make a reasonable argument that a product is the byproduct of a series of projects that have been brought to completion. That is a reasonable argument to make, although there are some important differences between project thinking and product-oriented thinking.

I like to think about missions or initiatives, and how those differ from projects. They do differ significantly from projects in the sense that they can be open ended. They don’t necessarily end with delivery. Which isn’t to say that all projects are like that, but that is a common framing of a project. The longer that you spend on a mission, the greater the suggestion that that particular mission is valuable, that you’re having success improving a particular metric or improving outcomes for your users, or accomplishing any number of things.

And that’s a huge difference to how most people think. Most people think that the quicker you get things done, the better. In mission-oriented thinking, yes, you want to learn quickly, and you want to quickly figure out how to offer more and more value. But you’re not constrained by this idea and to the factory metaphor of delivery— just dropping things off the end of the assembly line. Instead, frame things as bets as I discussed in the bet section.

Missions are also often nested. There are really small missions that might take a couple of days, and those that in some way feed into or are linked to larger missions that might take a couple of months, a couple of quarters or even a couple of years. The whole company is based on a series of missions, just like it’s based on a series of bets and beliefs.

The important framing is that a mission might also have a stopping function. The team might have an agreement about when they will decide that pursuing this mission any further might not be beneficial. That is very, very different than a predetermined definition of done, a delivery or state you achieve that clearly determines the endpoint. An example of a stopping function might be when the rate that we’re able to improve what we’re working on drops below a certain threshold. At that point, we might decide to reconsider. We might want to consider stopping, pivoting, or embarking upon a different approach.

An argument could be made that this is just semantics, that you can obviously just mold the project idea to encompass a definition of done for some kind of outcome. But I think that philosophically, what you’re talking about is shaping an approach that people enjoy. I think that humans do enjoy this idea of the initiative for the mission, and products risk devolvíng into a feeling of endless iteration. Having a container for an initiative does make sense on a human level. Reframing the idea of a predetermined outcome for the effort into improving someone’s life or improving a particular metric or entering your particular market can be extremely powerful.

Starting Together

Starting together is something that I’ve spoken and written about a great deal. The whole idea of starting together is that there is a tendency to send people upstream or to have smaller groups of people initiate work. And the fascinating thing is, if you ask a team what work that they have in progress, they’ll often show you some set of work. But when you ask what the people are actually working on—and I mean everyone, what is everyone working on—you’ll hear about lead architects being in meetings for something that’s supposed to happen in eight months. There will be PMs and user experience meeting for things that have potential. You often find that the amount of work that’s theoretically in progress is actually dwarfed by all of this planning and decomposing and pitching and discussing. The whole idea of starting together is trying to limit that planning inventory, trying to really kick off an effort with all of the people involved, and striving to minimize premature convergence.

This doesn’t preclude people trying to build context around something or understand the size of an opportunity or to set context. What it does mean is that instead of a small number of people dropping it on the team, you try to get the whole team experiencing the problem for the first time. I like to use an analogy from movies when the group of friends opens the door of a haunted house together and you see all of their eyes go really, really wide. That’s the sign that they’re experiencing the problem for the first time. You see a lot of movies where there’s a small group of people involved in the first 10 to 20 minutes of the movie. Gradually, they assemble the whole team after they’ve endured some trials and tribulations in the beginning. That’s the point where you get the team preparation montage, the tension builds a little bit, and they get all of these unique ideas and ways to solve the problem because the team has been assembled. That’s the kind of starting together that I’m talking about, because what you find in those movies is that a lot of that initial battling doesn’t necessarily equate to the power of the team once the team has actually assembled.

The whole idea of starting together is to figure out how you can plan a sequence, how you can arrange and construct your teams in a way that they can truly start working on something and clear their calendars. This is not, “Oh we do one meeting in the morning and then we continue to do business as usual,” it’s really just clearing their calendars so that they can all jump into this problem together.

And what might this look like? There might be customer interviews or joint research activities. You might have various people presenting bits of data that might be known about the particular problem. You might do customer visits. You might try to start doing some rapid prototyping. There are many different paths a team might take, and it’s difficult. You don’t want to adopt a one-size-fits-all approach to starting together—that’s not really recommended for anything. But the whole idea is getting everyone in the room, clearing out the time, and doing some kind of kickoff that really aligns people on the opportunity. Then you experience that initial exploration together, as a team.

When I see a lot of team struggles, especially in terms of getting things done, you can often trace it back to the kickoff. You can often trace it back to there being a lack of alignment. That might not even be the word you’re looking for, because poor alignment at the beginning is quite common, but if everyone is experiencing that at the same time, then when you actually do get to the point of a deeper level of alignment, the result is all the more powerful. Generally, the idea is to create an environment in which the team can experience the problem for the first time together and connect with the customer.

Coherence and the messy middle

One thing that you find when you talk to teams is that it is often very difficult for the people working on the front lines to connect their low-level work all the way up to the larger bets of the company. You find that the near-term work in the one to three-week, or even the one to three-month range, is usually pretty known because that’s what’s dictating people’s lives.

The larger company bets, the one to three-year bets are also known, but they’re almost by definition somewhat vague. They’re very directional. They don’t feel real at that moment. They’re hard for people to wrap their heads around. And then there’s a middle layer, which I like to call the “messy middle,” which is neither short-term work nor really long-term work. It’s those bets, the things at that level that teams often have the hardest time wrapping their heads around. They have difficulty conceptualizing how their work fits into that messy middle work, and how that work fits into larger long-term missions.

One of the reasons that this happens is simple: we spend a lot of time talking about short-term work and the large, long-term things. But once the bets have been made, often, that one to three-quarters of the work is not really discussed all that much. It’s only mentioned if you’re being very intentional about it. The key to building this kind of coherence is that you need to keep reiterating the thought behind the bets in that middle range: what you know about them, your progress towards resolving those particular bets. Have your beliefs changed? How and what are the teams doing? And even how those bets are related to the high-level goals of the company.

The important reason that you have to keep repeating those things is that when people talk about being more outcome-focused or impact-focused, almost by definition near-term work isn’t very outcome-focused. One exception is if you’re in an environment where you’re making these tiny little changes and a million people are viewing it that day, and you’re busy tweaking things day in and day out.

And if it’s a highly specific customer outcome and it’s not linked to these kind of powerful customer outcomes, it can take a little longer for you to understand whether you’re moving the needle on those things. For example, you could make something new possible for a customer. Yes, you’ve achieved an outcome, you’ve solved that particular problem, but it’s still unclear. It can often be unclear whether doing that thing had a more fundamental impact for customers. And that fundamental impact is typically captured in these larger increments, a bit like pebbles, rocks and larger rocks—boulders. These aren’t the mountains of the company, but they are the boulders of the company. If you’re not reflecting back on those things, it’s difficult. But back to this idea of coherence: one of the things that’s misunderstood is that people believe that you need certainty to have coherence. That’s not what you need.

Coherence is the ability to be able to navigate and link together the work that you’re doing in all of it’s messiness and all of its uncertainty and just tell a coherent or persuasive or connected story about how this relates to the larger things that you’re doing as a company.[a]

People often chase certainty, and the problem is is that when you manufacture a certainty, you actually limit coherence. The smart person in the room will look at that and say, ”Well, that’s not very coherent. We don’t really know that yet,” or, “We’re still trying to discover that, and we still haven’t gotten that thing going.”

Manufacturing certainty is not coherence. Coherence is taking the reality that’s in the room and visualizing it or presenting it in a way that people can understand it and navigate it. Coherence also doesn’t mean that everyone needs to think the same way; that would be building a false consensus. If you have three different perspectives, the coherent way to describe them would be to describe those three different perspectives and how they interrelate.

Multiple operating models at once

One thing that becomes abundantly clear when you talk to teams is that there are often many different types of bets in progress at once. In fact, you want a balanced portfolio of bets, which means that you’re going to have teams tackling very different types of work simultaneously. An antipattern you observe is that some form of process is expected to apply to all the types of bets in your portfolio, and that somehow you’ll find some one-size-fits-all approach that will work for that. You see this a lot in program or portfolio management. In essence, portfolio management should include a portfolio of bets, but everything ends up passing through the same gates, and teams are all expected to do the same types of things.

One thing you observe with higher-performing teams is that they tend to have a relatively stable set of patterns for how they approach all of the things they do, while also being able to absorb the unique nature of the different types of work that they’re doing.

One great example would be where some companies get a lot of small customer feature requests which, if they could just knock them out, would have a relatively low blast radius. They’re pretty easy. They make sense. How the team approaches working through those is very different from how we’ll approach more exploratory efforts. This requires an approach that will accommodate both. Now, what’s also really, really interesting is that when companies realize that they need different operating models and and the ability to run those in parallel, one temptation is to completely factor out those teams so they don’t interact at all. Now, that does have some benefits, but it can also be demoralizing. For example, if you’re working on one effort in the company and the company’s constantly starting these very interesting innovation efforts and they’re not letting anyone participate or giving people an option. Running concurrent operating models or things in parallel is actually very nuanced and difficult. It is not a silver bullet that is going to solve all your problems. It actually takes a lot of work to get right.

Another big area where this manifests is that a lot of teams approach things in an approximately agile way. There’s this idea that all things are somehow emergent: architectures are emergent and all these things are emergent.

But there are certain classes of problems that are riskier from an architectural standpoint and need to be thought through more carefully. You need the right people in the room, and they need time and space. That’s another example of how trying to treat all things as “Let’s just get started and see what happens” doesn’t necessarily apply in every case. The relevance of this for product is that often, product managers with different skills might be really adept at tackling different types of bets. Some people might be extremely good at things involving a large number of partners, for example, or understanding the business landscape or the partner landscape. Another person might be really amazing at extremely disciplined, tiny incremental improvements.

Layering one on top of another, someone else might be great with new ideas, an enthusiastic idea person who likes to be involved really early in validation. This relates to how you staff, and it relates to what you’re doing. An interesting model I heard about recently is that someone talked about areas where they were playing offense, areas where they were playing defense, and areas where they were diversifying that specific model. This is something to keep in mind.

Data as a trust proxy

One thing that you observe as teams grapple with using data, measurement, insights, or any number of things, is that there’s often this idea that data will serve as some kind of trust proxy. That somehow a piece of data will settle all the ties in opinion, that the highest paid person will suddenly stop enforcing their opinion with other people, that suddenly you’ll have all this certainty about what you’re doing.

What this misses is that when you see teams making effective use of data in their environments, there’s often a lot more uncertainty. There are a lot more questions about why what you’re doing isn’t working. There are wide spectrums of confidence. When you initially embark on some effort, you only have rough assumptions that you’ve baked into the metrics that you’re tracking or the analysis that you’re doing. Over time, your confidence increases, but it is an ongoing effort. You have to renounce the idea that the data will pass/fail your teams or will once and for all tell you if you’re moving in the right direction. Instead, it’s important to adopt a learning stance, one that acknowledges measurement as a catalyst for learning. You’re peeling away the layers, and measurement doesn’t instantly give you some hard kernel of truth. It may, however, help you peel away one layer of the onion and better understand more of what’s going on.

You see this as well in situations where people imagine that there won’t be any more need to do qualitative research or to connect with users or customers. An erroneous belief can develop that everything will be like a science experiment. But what I’ve observed in talking to these really high-performing teams is that it really is an art. There’s a lot of luck involved in what we do, and a lot of fortuitous timing.

The idea that you’re going to structure these perfect experiments and collect this perfect data and shut everyone up and make your bulletproof case to management must be tempered by the reality that it often doesn’t look like that. There’s a quote that goes,“If we have data, let’s look at data. If all we have are opinions, let’s go with mine.” What I think is kind of funny about that is that there are so many ways to warp data. There are so many ways to twist it, that people often use it to simply back up their opinion. There’s a lot baked into that statement in the sense that people’s priors, the stuff that they’ve observed, their instincts and other things, are pretty valid.

They are valid things to consider, in a sense they’re even data. It might not be as crystal clear as other people’s version of data, but all that stuff is data. So to create an environment that is conducive to being more evidence-driven or data informed, you need to create a safe environment for uncertainty, an environment where people are open to the idea that you’re iterating on how you use data. For example, initially you might only have some very rough KPIs.They’re a useful mechanism to accurately communicate your beliefs. Now, over time, you might really begin to build a deeper picture of causal relationships between things, to develop predictive models to be able to prove and disprove things. But initially, you’re lucky if you just use these things to represent your beliefs and move forward.

Chronic vs. Acute Issues

I’m always struck when people read a blog post from a popular company and then say things like, “It’s perfect there, look at how well that’s working,” and “Why can’t we work like that?” As someone now who’s managed to talk to a lot of those companies, one thing I can say for sure is that it doesn’t get easier. Maybe you learn faster or you go faster or have more impact. But a lot of the acute challenges that arise happen in those particular teams. Interestingly, I would say that the difference is that there tend to be fewer chronic problems there. Such organizations find a way to be resilient and to prevent things from becoming chronic and to solve more acute issues.

You’ll talk to an executive who’ll say, “We’ve got all these problems, but we tend to just knock out the ones that are really limiting us that people bring up.” And if you talk to the employees on those teams, they’ll say the same thing. They’ll say, “Nothing’s perfect here. We’ve got our fair share of problems. Two years ago, we encountered that, and we kind of worked it out. And a year and a half ago, we encountered this other thing. We worked it out.” These companies have a sense of self repair, a sort of immune system. The company is strong—but it’s not like they don’t get sick and get a fever—but they’re eventually able to fight off these particular issues.

Now, compare that case to companies that seem to be struggling with a lot of chronic issues: companies that are carrying a lot of debt, or where it might take years for a toxic person to be let go, or that have been affected by a merger or an acquisition (perhaps they still haven’t resolved the issues of how the parent company should interact with the acquisition), or any range of things like that.

From the outside, there’s often an impression that everything is rosey, but that’s just not the case. What distinguishes them is this element of self repair. What’s very important too, as you talk to these companies, is that it would be easy to say that the silver bullet to achieve a self-repairing company is transparency and other things (psychological safety would be a good example). It might be easy to point out commonalities between those companies. But when you dig deeper, you see that the way that that company achieves that positive net effect, that ability to self repair, can vary greatly depending on the company culture.

As a result, you might see one company that’s actually pretty hierarchical. They have many layers of management and teams which are rather isolated and which don’t necessarily have insight into the inner workings of how the C-suite is resolving these chronic issues. It’s not really out in the open, but it happens, shit gets done, problems get resolved. Another company might be extremely transparent, extremely flat, with high transparency between different groups and much more openness about its warts. But the net effect is the same: both successfully deal with those chronic issues. This goes beyond truisms like “toxic leaders are bad,” or similar platitudes that could apply in many different situations. You’ll find unique approaches that individual cultures have developed for helping information flow to the people who need it and for resolving chronic issues.

These approaches and who’s involved depend a great deal on the culture. In some cases, you can see that it’s derived from the management layer, in others it’s more a result of work by the front line. And in still other cases, it’s a strong CEO who believes incredibly deeply in a handful of things happening in their company. The mistake is to assume that all of these companies are healthy for the same reasons. Although you can find commonalities, digging a little deeper reveals a lot of variety.

The attraction of short-term thinking

It’s almost impossible to find companies that aren’t struggling with the tension between mid and long-term outcomes (and upside and potential) and the pull of short-term demands. Any company that says that they’ve solved this problem is probably lying; it’s always a balancing act. I think that has to do with the fact that in our personal lives, we have a hard time thinking about the mid to long-term. We get distracted by shiny objects, we get pulled into the magic diet, we get are constantly being drawn into success theater in our own lives. Observing a cross-section of companies, you see the same dance being played out constantly.

There are a couple of solutions to this. One is to be very stubborn. Many people who’ve had multiple failures in their careers start to develop a level of stubbornness about what they’re doing. This often relates to not chasing short-term outcomes. It’s a level of stubbornness related to how they want their company to be—leaps of faith that defy the short-term—that they feel will build a more resilient company in the long run. This is very difficult to do. For example, if you’re a first-time startup founder without a track record, and you have investors dogging you to create this kind of short-term growth.

As people become more experienced, they begin taking this more disciplined, almost stubborn approach. You’ll see this reflected in much of what has been written about Netflix. The founder, Reed Hastings, had had certain experiences in previous companies. This led to the writing of the text “Netflix Culture: Freedom & Responsibility,” which has become a very popular bit of writing. They went out of their way to make sure that the things that had happened in other companies would never happen again moving forward.That’s the level of stubbornness I mean.

The other opportunity is to compress the durations of activities. The standard problem with these short-term gains is that they can generate negative side-effects. If you try to build quickly, and in the process introduce a lot of technical debt into your product while chasing some short-term outcome, you will only feel the impact of those decisions after a certain amount of time has passed. This lag time impacts your ability to course correct.

One option is to become better at sensing the early indicators that you’re going off the rails, and then feed that back into the decision-making mechanism. And that certainly is what you see a lot of companies doing well. It’s not like they ignore the pull of short-termism and short-term successes, but they are very good at recognizing that something is wrong based on the early signs. Not only that, they’re very good at acting on those signals when they are detected. An example would be a team that raises a red flag when they begin to sense that they are accumulating a lot of technical debt. Or perhaps things are being impacted by dependencies that weren’t previously apparent. The organization would then be able to initiate efforts to address that problem. This goes back to the idea of chronic issues versus acute issues: the most successful companies simply allow fewer chronic issues to develop.

The time it takes to get good

It does take time to get good at this—or to get good at anything. But you observe again and again that companies trying some new process or technique for the first time often incorrectly expect to see immediate results and to be good at it instantly. Frequent examples of this involve research sprints and approaches to measurement or mapping.

I always like to mention that I worked in a company environment that was really pretty healthy. It was a great product, and there was a good attitude towards product. New junior people like designers, engineers and product people would join the company straight out of college. Full onboarding took time: it took as much as 12 to 18 months to get them to the point where they were really starting to grasp being given a more open-ended opportunity and had the ability to extract value from it.

This allowed them to really come into their own as product developers. Not only that, it wasn’t just the 12 to 18 months, it was repetition. It wasn’t just one big effort. They went through the mission cycle. They went through the cycle of encountering a new problem and tackling that problem, over and over again. And importantly, they were allowed to fail. Early on, they weren’t all that great at it. But instead of someone coming in and simply saying, “Well, you guys are doing it all wrong, and this is exactly how to do it,” there was a level of safety at the company where teams that were wandering off in the wrong direction were allowed to wander off in the wrong direction. Now, consider the power of that for a second. If all you’ve done is had people stop you from making mistakes, you haven’t really learned the hard way.

But if you’ve done something where you’ve gold plated a product or misread the problem or gone off for weeks or months in the wrong direction and really got to understand how gnarly that can get and what a quagmire it can become, you become that much stronger in the future in terms of your pattern matching and your resolve to make sure that that type of thing doesn’t happen again.

The takeaway when talking with teams is that they often believe it’s just about mastering a particular framework: “Oh, we’re going to install this framework and it’s suddenly going to fix things.” And it really doesn’t. There’s so much nuance in product development, so many moving parts and intricate facets, and the work itself is often so varied that it’s very difficult to instantly learn something.

There are myriad little patterns that you have to get good at matching to be successful. The consequence is that it takes practice and repetition. With repetition, it’s not just that people talk about agile and sprints, “While we go sprint for sprint, we’re learning.” Often, it takes months or even quarters for some bet to fully come to fruition. Certainly, you are learning every week. You’re learning every day, you’re learning every time you have an opportunity to reflect on what’s happening. But sometimes the biggest learnings take a year to materialize before you really understand how the whole thing played out. It’s important to keep this in mind.

The final thing related to this need to practice is the safety that allows people to speak freely about their experiences. It’s easy to point to “fail fast,” but that doesn’t do justice to the safety required within an organization to let people fail and then talk openly about what they might have done better, which enables people to make progressively better decisions in that environment.

It’s hard, and it takes practice, it takes a supportive environment, and even really experienced people need to practice when they shift domains or move to a new setting. It just doesn’t happen.

Play Less Tetris

You end up meeting a lot of product managers who consciously or unconsciously perceive part of their job as loading up teams, engaging in what I view as an elaborate form of Tetris. They’re looking at individuals and saying, “What are they doing right now? Maybe they could take these three other things, or maybe that other team could split things up five ways—20% each, or when that engineer’s done with that one thing, I’ve got this next thing that I’m going to load up on them.” Or, “What can we fit into this quarter while we fit these other things? But there’s this other thing, and maybe I can negotiate this and move this around.”

One of the underlying components of this is the idea that it’s part of their job to till people up, to get more output. This is not limited to just product managers. You see this with engineering managers a lot. You see this with individuals a lot; as individuals, we also try to play Tetris with our time. We try to play three dimensional chess with our time—all the time. Consider when we’re blocked on one thing and then immediately try to fill up that time instead of unblocking ourselves. Or we don’t even allow ourselves time to contemplate, or use slack time on our own, which is valuable.

The important side effect of playing Tetris is that it leaves less time for experimentation and less time for exploration, etc. When we believe it’s our job to keep people busy, we tend to pre-converge on things, and we tend to rush things so we can drop them on teams. We allow less time for teams to truly start together, and we engage in dependency wrangling, something like, “What else do we need from these other teams to make this possible?” Five other teams are asking that same question. Maybe you have teams juggling 15 things at once for 30 different efforts, and all of those things come back to bite you. And as it relates to measurement: if everything is predetermined in the game of Tetris—the puzzle pieces have all been placed—you won’t have the leeway to iterate on things or to explore options. You’re going to be locked into a particular plan because you will have over-constrained yourself so much with all these commitments and individual backlogs and other things that you’ve put together. This is a really important thing to keep in mind, and that I see over and over: you have to release yourself from the Tetris game.

The difficult part here is that engineering teams are often looking to product to play Tetris. “Oh my goodness, why don’t we have another thing to work on right now?” Now, the minute that you say to them, “Can Joe work on this or can’t they? Because if Joe can’t work on it, then I have another thing for Joe,” you’re also encouraging this on the part of the engineering team, encouraging a high degree of specialization. You’re encouraging them to not necessarily treat things as a whole team. It’s very nuanced and very hard to break the habit of playing Tetris because there is a lot of pressure from all parts of the organization to keep playing. There is an idea that an engineer who doesn’t have their fingers typing on a keyboard at any particular time is somehow this massive waste. And that as long as there’s a free hand, there’s certainly some way to start some new thing that you’re working on. That’s Tetris in a nutshell.

It’s a bad habit to get into as an organization, and you really can’t embrace some of these more experimental, open-ended and impact-driven approaches when you’re actually optimizing to keep people busy. You are what you’re optimizing for. And if you’re optimizing for keeping people busy, you won’t be optimizing for outcomes in talking to teams.

Moving fast and slow

A lot of organizations place a heavy emphasis on moving quickly and on output. You even see some pretty popular companies brag about how many features they managed to complete in a certain period of time. Maybe that’s good for those companies.

But there is a contrary movement. Designers and architects are often associated with the idea of questioning this pressure to move because it involves cutting so many corners. “We’re putting crap out there—why aren’t we taking our time? Do we actually need to deliver this quickly?”

The arguments are polar opposites. Teams that appear to be doing well are actually able to incorporate these impulses in a way that results in a bias for frequent integration. By that, I mean a bias for learning, for integrating assumptions and then testing them, and for making sure that they don’t go too far off course chasing some silver bullet. In fact, there is a bias for shipping or testing—for action. At the same time, there is longer-term thinking involved, a habit of leaving room to iterate on something and to explore. These teams allot time to “bake in” the product and investigate whether it’s working or not. This is a more deliberate approach.

A classic example is a team that’s shipping quickly. The flip side of that is a team that is shipping pretty quickly, but which is also learning as fast as they are shipping, as one coworker put it: they’ve harmonized learning and shipping. This is often surprising to designers, who are often used to situations where, unless they really dig into the problem and think about the solution, they run the risk of everyone just cutting corners and dumping an inferior product into the world. The idea of leaving room to truly iterate is foreign to a lot of designers.

If you put someone in the situation of always being fearful that someone’s going to yell “ship it,” of course they’ll gold plate what they’re doing. They will also be pretty resentful about all these iterative practices because the iteration is not being done in service to a better outcome. Iteration instead becomes shorthand for “releasing crap quickly.”

One idea to keep in mind is “working fast and working slow,” of remembering that there are benefits to rapid learning, integrating and testing where you’re at, of putting the pieces together quickly. I have a friend who is a VP of engineering. When his engineers are having problems moving at all, he adapts their work scheduled to do one-day sprints. That might seem terribly inefficient. And to an outsider, it is inefficient. But it’s sometimes better to have that bias for action than not, to be granted the power and the ability to do that. Some recent studies indicate that these top-performing teams are deploying often and and integrating often. It’s a skill and a power, but if you’re not using that power for good—if you’re not truly closing the loop on the learning—you run a terrible risk that you’re going to end up with a lot of crap in your product. Really think about balancing the bias to action with the bias for learning.

Storytelling, repeated stories

One thing that becomes clear when you talk to teams that you know are doing well (i.e. increasing their market share and making humans love their product and all those types of things): they tell very coherent stories about how they work, and the way they describe how they work is very disciplined. Here’s what I mean. When you ask someone, “How’s it going? What are some recent product decisions? What is your product strategy?” a less experienced person will say, “We’re working on this right now.” But there’s not a lot of context around that.

When you talk to someone who is really on top of their game, they will paint the whole picture and how what they’re working on fits into the broader story. They’ll say something like, “In our company, there are three major forces that we think will shape the market for the next six years. This is one big unknown, and here’s another. Our unique edge on this is that, and the way this translates to our six-month areas of focus involves three primary puzzles that we’re grappling with,” etc. That will continue until you are given a coherent, holistic picture of the situation.

This is important, as it is when they talk about their recent product efforts, because there’s a depth to their explanations. They are discussing their assumptions. They are talking about what they thought happened. They are talking about what they learned and what surprised them. They’re talking about specifics: details and data—both qualitative and quantitative. And they’re telling good, meaningful stories, not vague stories about what happened in the last six months. This is important because this storytelling, this repeated reflection on what’s going on, this repeatable consistency in you’re describing is a real hallmark of these great teams. It’s something that you can practice as a team as well. Companies frequently have tech talks where they mention things that have shipped recently; this in-depth reflection happens a lot less frequently.

The team is getting up in front of the company and sharing these stories internally, talking about their missions in an honest, transparent and in-depth way, about their trials and tribulations, about what they learned and what they put out there—both the positive and the not-so-positive things. A lot of sharing takes place. This goes beyond simple dashboards, and it goes beyond someone just pointing out a big win at a quarterly meeting.

It’s the depth of their dialogue about the game that they’re playing, the bets that they’re making, and what they have learned—that is the muscle that you need to build, and it doesn’t come naturally. It’s also something that a lot of teams don’t leave the time and space to reflect on. Taking to product managers, they often say, “I’ve been meaning to write this blog post for a long time about something that we did. People internally are asking me about that.” To them, this is an extracurricular activity, and most of their time is spent on the stuff that’s happening right now or stuff that they’re trying to pitch. The trick in this regard is to carve out space and time for storytelling and for sharing experiences and building up that muscle for real coherence about how your work fits into the bigger picture, including what you have learned. And that’s a real superpower.

Strategy and its relation to beliefs

Especially in teams that have really begun to embrace the idea of working very iteratively, of working with sprints or other similar things, strategy can often carry a negative connotation. It’s big, and there are a lot of assumptions. It’s something that executives put in PowerPoint decks. It’s very tired, and it’s a lot of talk. But it boils down to other things that we’ve discussed: there are a lot of product teams that almost have their hands tied, which doesn’t make sense. Another way to put this is that their future is largely dictated by a number of decisions about which markets to enter, which personas to target, where they think the market is going, what competitors are doing, and what’s going on in general. I think purists will say that if the product is good, it makes everything easier. So we end up focusing exclusively on solving a human need, and we’ll be good, which I actually truly believe in. I think that that’s a great principle to follow.

You see a great number of really promising products with a strong design culture. They’re doing a great job of connecting with that human need, but they aren’t really paying attention to the sea changes and the shifts and the broader gameplay in their particular market. What I like to ask teams is, “Which wave are you riding?” You see certain problems that over the years, multiple waves of people have been trying to solve. Some companies get in early and then perhaps become too big to innovate. Some people get in later and have the benefit of access to new technologies, but they can’t really compete. Some people enter later thinking that the problem is really X, and then the whole industry is turned upside down by some form of disruption.

And the reason this comes up in a lot of these talks is that someone will be obsessed with measurement in the here and now. There’ll be talking about some workflow or about how to measure this initiative to know it’s working. When you dig deep into their product strategy, you realize that there are these fundamental bets. There are these fundamental questions or moves that they’re making (or in some cases not making) that have a much greater influence on the approach to measurement that needs to take place. A lot of the work they’re doing at the moment consists of tiny little step changes, of improvements further up the funnel or in other parts of their business.

There are glaring questions about how the business will operate. A classic example of this is when a company is struggling to find product market fit. It’s easy to get distracted at that point and forget that you’re really in the stage of trying to find product market fit. There are also a variety of sub-stages of finding product market fit, which can be distracting.

This isn’t a suggestion that you just need a bunch of PowerPoint decks with lofty projections on the whole space. But it is important to lay out and map the core beliefs of where you think things in your industry or space will move. You should identify where you are relative to legacy solutions, relative to your potential disruptors and relative to your current competitors—the whole stack of what you do. Frequently, a company thought they were a banking company, but under closer scrutiny they discovered that they were actually a data company.

At that point it’s “Oops, now we’re competing against all the other data companies.” Think about strategy and how that relates to your beliefs.

Prioritizing Opportunities

Prioritization is a huge topic and there are many approaches to thinking about it. One pattern that I see repeatedly, which is troubling and which almost serves as a blinder for teams, is a common way to think about prioritization: value and effort. Is this high-value, high-effort is a very simplistic way to think about it. It’s very simplistic because often the most valuable things you’re working on are huge multiples more valuable than the low-value things you’re working on. In terms of effort, there can be a wide range as well. It doesn’t really take into account things that are more friendly to experimentation, where you can iterate your way through. There is an area of confidence, and there’s risk. This relates to much of what we covered when talking about the intricacies of bets and how they work.

But if you step way back, I can paint you a picture. As a company, we may believe that there is a big opportunity if we really made a certain actor or persona a lot more efficient in the way they work. We think there’s a huge opportunity there if we can accomplish that. And there is a whole plethora of ways that we could try to make that happen.

Some of those are big lifts, and some are small lifts. There’s just a whole variety of ways that you can move them. But if we also consider our product strategy, that opportunity is by far the biggest opportunity that we can work on. Now, this ties together with some other things we’ve talked about, about premature convergence and starting together. The tendency at that point is to say, “What are we going to do to exploit that opportunity?” Someone will say, “This is low hanging fruit. There are other things that we could take care of. Here’s a level of effort.” The prioritization goes like that.[c] Things are then sequenced based on that opportunity size, adjusted by effort. Now the danger at that point is that we often forget how important that opportunity is. So instead of saying to a team, “There’s this huge opportunity. We trust you. There might be some small stuff or some big stuff, but whatever you do, if you can just keep it pretty snappy and experimental in the beginning, it’s going to be good for us. We just need to explore and extract that opportunity.” Some team has already begun discussing who might tackle a thing, and we’ll tackle this other thing. Or they’ve committed to doing this particular item. The important point here is that when you’re prioritizing, product should really consider prioritizing by the size of the opportunity and try to resist taking on too many opportunities at once.

The temptation is to split things apart and prioritize interventions prematurely, before a team has really had a chance to tackle that analysis. From an engineering standpoint, if you’re a shared team that might do infrastructure work for many other teams, and someone is asks you to decide ahead of time if you are going to solve a problem (to play Tetris with your own backlog in order to do all of these things), it can be really misleading. It can be really suboptimal in terms of what you get done. When you prioritize by opportunity size first, you resist making all of these assumptions about how the work will happen, how it might be split between teams, how shared teams will be involved, and what you’re going to do. You keep it crystal clear from a product angle that you believe that this opportunity is the largest thing. For me, if an engineering perspective determines that we want to get five teams working on that because it’s that big of an opportunity, “We’re going to get it done in a third of the time,” or “We have this novel way to try to make this possible,” then it’s amazing—you don’t want to impede teams from being creative about how they’re going to attack opportunities by already breaking them down and prioritizing solutions.

Learning Cadence

We have touched on this in some of the other sections, but I wanted to zero in on the idea of learning cadence and to differentiate that from a shipping cadence or delivery cadence. The best way to tackle this is to imagine that you have asked a team to talk about a handful of things each week that it learned about customers or users. What would they talk about? What would be the volume of that learning? What would be the depth of that learning, and how might it shape what the team is doing right now? A question that I ask teams a lot is “What have the big Aha! moments been that really created a pivot for you, that really forced you to rethink how you’re approaching what you’re doing?”

The variety of responses to that question is amazing. Sometimes it’s, “About six months ago we changed our strategy a little bit based on some learnings from maybe eight months ago, but now we’ve been pretty much in execution mode, and we’re just rolling through and moving on that.” And then you get other teams that say, “Wow, I can’t even begin to count the number of things that we’ve learned in the last six months. We’ve learned that users did this. We made this mistake. We learned this from someone else, and we’ve been getting feedback from the market that this other thing is happening, while also tweaking something else.”

They review the last six months, and it’s just learning after learning about what they were doing. This helps me think about what the learning cadence or velocity is for a particular team. I say “cadence” because there’s a kind of cadence with which we reflect on things, and it’s very layered and nested. You might be learning little things every single week, but in terms of the larger chunks, maybe one to three of those bubble up every six weeks or every quarter. This learning velocity is a really powerful way to understand what’s happening and how your team is working now. Often, when a team or a small group of designers or strategists has a fair amount of upfront research, they’re doing a lot of learning.

There’s rapid learning every day. With every customer conversation, you’re learning something, and then you see this shift: you’ve got that learning, and now you’re trying to exploit it in a different context. I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with that, and that certainly makes some sense. But you have to contrast that with teams that may do a bit of that deeper upfront learning, where they’re always revisiting those assumptions. They’re revisiting to see if they are on the right track. And probably most importantly, they’re acting on that learning. I think that that’s one of the difficult things. You see teams that have shipped something, and they started amassing this list of requests and bits of feedback, and honestly, then they’ve been redirected to something else. So yes, they’re learning, and yes, that’s entering their system, but they’re not turning around and acting on that learning immediately, converting that knowledge into a change of direction. The important thing is not just learning, it’s responding to what you are learning. There is no right or wrong. Sometimes there is a lot of learning all at once, which then drifts into a little bit more exploiting than learning, with the pendulum swinging back and forth.

But this traces back to when I’m talking to these teams and it’s very evident in their conversation. They’ll just say, “In the last month, we really picked up on this, and we learned about this, and we learned that we were wrong about that.” And the differences between people who can and can’t really answer that question at that point are quite evident, especially when they talk about acting on what they are learning.

Learned helplessness

Sometimes, when I’m talking to a product manager, they’ll say something like, “I wish my team would be more interested in research and exploring the problem. I’m not sure why they aren’t.”

This is a really interesting question because people certainly have a range of interests. I have engineer friends that say, “It’s not my job to figure out what we need to build. My job is build.” I respect where they’re coming from. I have other friends who are engineers who say, “I’ve kind of given up on what our PM does. I can’t make heads or tails of it. So I’m just checking out. I just want to focus on the technology. I just want to focus on this. And honestly, I don’t have a lot of confidence in what they’re doing, but it’s just better this way. I don’t get involved in what they’re doing.”

That’s a bit different, right? That suggests that they’re interested, but they’ve probably gotten burned a couple times. You find these attitudes in environments with incredibly low psychological safety, where engineers and designers, etc. are interested, they want to discover the problem, and they want to have more impact. But they just don’t. Either they aren’t enabled or empowered to go upstream and get involved, or perhaps they got involved in the past and got swatted down for doing that. There’s just this harsh wall that exists.

The challenge, I think, is that I’ve observed teams that just become really evolved after practicing a lot. In those teams, designers and engineers can pretty much do almost all of the activities generally associated with a product manager, which frees up that product manager to be more strategic and think about other things. It’s wonderful to see teams where that has happened.

But if you as a product manager get into the habit of just making these kinds of overly prescriptive statements, the team will adapt and optimize around you doing that. They’re going to optimize on you trying to put this kind of solution on the plate. As a result, even when they want to get involved, they haven’t really practiced enough, and it’s all a very new experience to them. I do think that we all fall victim to a certain level of learned helplessness in product development. This happens when we optimize around some less than great pattern over a long period of time. It really becomes ingrained in the culture, and it becomes incredibly difficult to break out of. I think the mistake is to assume, as in the example I started with, that when the product manager asks why their team isn’t interested, that it actually is because they’re not interested.

Instead, maybe they’re nervous because they haven’t really done that before. This causes resistance. Or they’ve been burned a couple times, or no one has really explained why it would work better if they got involved, or any number of things. When you actually do get these groups together, groups of marketing folks and the CEO and the developers, they’ve simply not spent any time communicating together. And there’s what Amy Edmonson refers to as a kind of professional culture clash.

There’s a little bit of learned helplessness with that, too, it happens. In short, you have to be very careful what patterns you allow to slip into a company because it becomes very, very hard to unwind those later. Even if people want something different, it can be incredibly difficult.

Data snacking vs. Integrated approach

In these conversations, you often notice a difference between what I would term “data snacking,” and a more integrated approach. In the first, people cherry pick data to support a particular effort that they’re engaged in, or perhaps to answer one particular question. Not that there’s anything wrong with answering questions, but here, the whole idea is that insights serve the purpose of occasionally agreeing with and supporting what you’re doing at the moment.

By contrast, what you notice with teams that are making better use of data (and measurement and insight), is that data is integrated into many different facets of product development. This isn’t to say that these teams are completely data-driven, rather that qualitative and quantitative data is woven into the fabric of all of their various efforts as a team.

For example, in kickoffs, you’ll see context being presented as data. You’ll see data about the problem, and as the team presents it strategy, you might see the strategy represented as a model of particular metrics or beliefs. This can be supported by qualitative data. As the team is reflecting back on what it’s doing or did the last quarter, the metrics that they’re using provide context.

The important thing is the presence of a consistent language around the bets that they’re making and the inputs and outputs, something that transcends one particular effort or feature. And that’s powerful because if you think about things like annual strategy reviews or quarterly reviews (or kickoffs or retrospectives), it’s really important to have a common thread between them. That is a hallmark of teams that appear to have a healthy perspective on using data.

For example, a lot of people incorporate OKRs into their goal-setting framework. What can be interesting is that teams will have their own Objectives and Key Results that might be completely decoupled from the business model or how the C-suite is modeling it’s particular objectives. They’re very localized to particular teams, and they don’t really tie in to the larger approach to what’s happening.

Another example might be something like when a team is embarking on a particular mission and they have some sense of the behavioral change they’d like to create. They have a sense of how they think they’ll benefit the business or the users or customers. They have some sense of the baseline behavior. And great teams will use that as a common framework throughout the mission to reflect on whether they’re moving in the right direction. It’s not just for show, it’s not just the PowerPoint presentation to pitch other people on the particular effort. They’re actually closing the loop on their assumptions and closing the loop on what they’re doing.

I think that another way to think about this ties into using data for learning, and not just as a stage gate or phase gate or getting the thumbs up for your effort, or as a pass/fail for a particular team. When you take the approach of using it for learning, you want to make a special effort to build up a larger framework beyond just answering one particular question or getting the magic insight. That’s a common thing you see: people expect some magic insight that will crack open the whole year of work. And in teams that integrate this, it’s a much more rigorous, cyclical species of reflection using all forms of data that gets them to where they want to go.

Functional feature factories

I have spoken to many companies, especially for business-to-business software, that are what I could most aptly describe as high-functioning feature factories. I would divide them into three categories. (The first is a massive over simplification, but you’ll get the idea.)

Imagine you have a company that can’t get anything done—or if it gets anything done, it’s completely unusable. They’re always chasing silver bullets. Really, nothing is clicking.

Then you have what I call “functional feature factories.” They release reasonably usable features. Customers are grateful (“That that was something we asked for,”) and they are not obvious duds. They keep chipping away at what they’re doing. The main thing that defines these companies is not that they’re doing terribly, but rather the lack of serious focus and step changes in their product, things that really help their customers do their job a lot better. The price points aren’t all that high, so people will churn if it’s not really providing that extra special value.

The third type of company is one that really nails high decision quality and high decision velocity by limiting the complexity they’re adding to their product in relation to the outcomes that they’re creating for customers.

In the middle category, they have an impact level of 4 to 7 on a scale of 1 to 10; they’re chugging along. Sometimes they land a dud that’s a 1 or a 2, but mostly they’re in the range of 4 to 6. But they don’t really have those extended 10s. They don’t knock it out of the park repeatedly or in a disciplined way.

The third category also has some duds—in fact, they often start out with duds—but they’re really pivoting and learning and leveraging that learning to practice a disciplined, repeated, systematic approach to introducing step changes in their product. They can’t predict exactly which one will deliver that result, but they managed to accomplish it.

Why is this important? I think that for most companies that have survived long enough to still be in the game, it’s not likely they’ve been doing anything terrible. But for a lot of these B2B companies, they eventually begin to struggle with the oppressive complexity in their product. They’ve just tried to play too many games, and it’s hard to really manage the result. They’ve made too many promises to customers and added too much complexity to their offering. This makes it very difficult for them to expand on their product and do really special things. Again, it’s not for lack of reasonable usability. It’s not even for lack of being able to move very quickly.

The important point here is that there’s obviously this broad spectrum of the types of decisions you’re making. For example, for some of the highest-performing companies that we know of, at least considered from the angle of their product team, maybe 40% of their initiative-level or mission-level decisions turn out to be great. Maybe only a very small percentage of those turn out to be knockout wins. It really puts into perspective how much complexity we risk adding to our products without creating a requisite amount of value for our customers (which we can hopefully monetize for our company as well). It’s an important thing to keep in mind.

Left to right factory lines

Although product development is often referred to as “knowledge work,” there’s a strong temptation to view it as a kind of factory line. In fact, a lot of the tools that we use reinforce this idea.

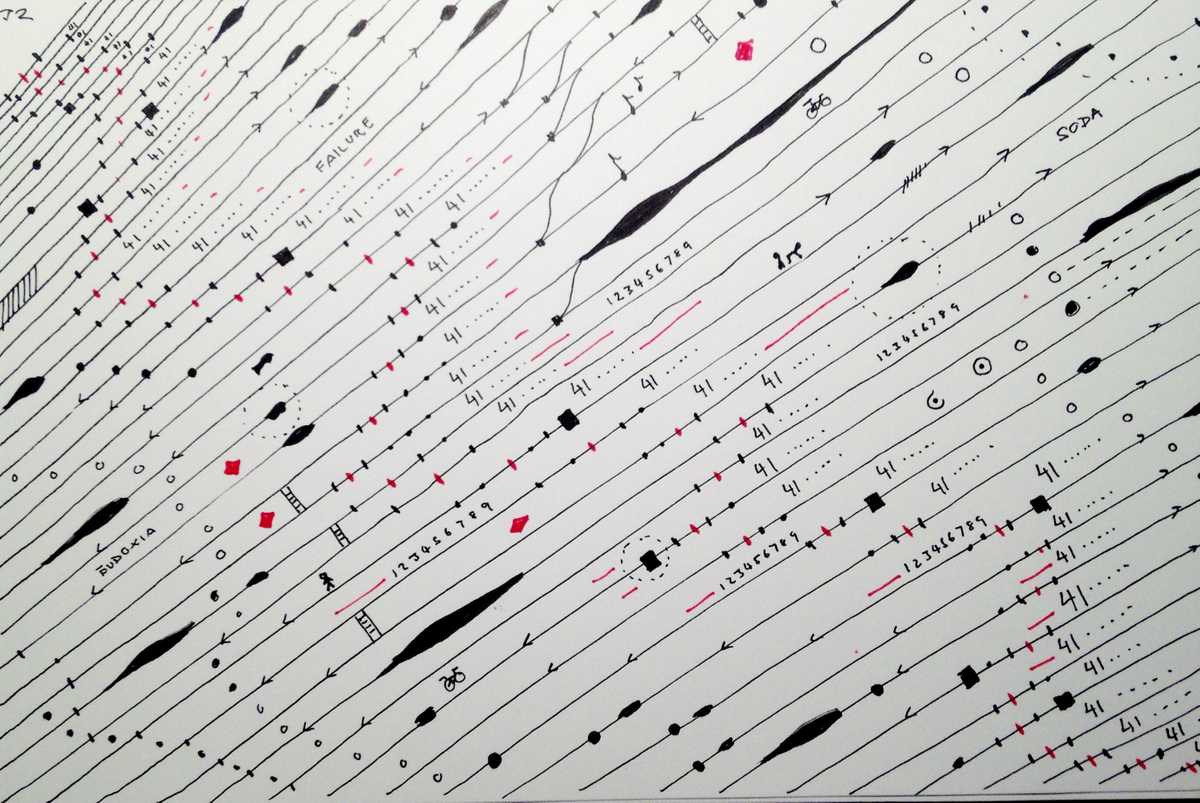

Imagine a popular tool like Jira: you view a work item on a board and then move it to “done.” Now, the problem with this is that very few of these tools accurately communicate the relationships between work at different levels, its interrelatedness, and its true nature as multiple loops. We’re generating feedback from these individual items and moving them into the system for the purpose of getting work done. It obviously helps to have some kind of visualization of your work in progress—and it’s a good exercise to limit work in progress. But again, these tools are not adept at really communicating the essentially iterative nature of the work being done.

Experiments are not great at communicating the idea that we might have three overall big bets in our company for the next couple of years, and that all this work is lined up. Visualizations are largely good for creating a delivery focus. In our context, we need to think a lot more about how to augment these production-line views with things that help us wrap our head around how we’re doing overall.

For example, if we’ve got a particular mission, and we’re attempting to improve a metric or other aspects. In addition to this delivery-based or ticket-based view of the work, it’s really important for us to understand our various releases as they contribute to improving a particular metric. This includes all of the various feedback loops that we’ve generated and how that work is linked into the other things that we’re doing.

What you often see teams do is augment the predominant delivery views of work. These views are what many people spend much of their day looking at, and even roadmaps and swimlane diagrams continue to reinforce this delivery mindset. Teams augment those views with additional views of how the work and their beliefs are related, and their progress with these tasks. You could ask what harm this kind of factory line mindset could cause to the outcomes that we’re trying to achieve with the least amount of complexity. There is a risk with any tool that accidentally encourages or incentivizes “more-is-better” without offsetting that against the idea of rapid learning, removing complexity, or the overall health of the system. Anything that does that in isolation is dangerous.

A good example of that is when quality drops, teams easily slip into reactive failure mode. Often, that work becomes considerable: dealing with issues creeping in from the side starts to eat up a lot of time. And unless you think about that and consciously consider how to bubble up that insight, you’re liable to continue plodding away on all the work that you think needs to be done without thinking about the improvements you need to make to limit it in the first place. We’re working in a complex system, and not just left to right. It’s much more like a value creation network with lots of interrelated feedback loops.

Modeling the business

Talking to teams that have had some exposure to the universe of advice for startups relating to growth models or software as a service metrics reveals that they have internalized some models relating to growth. This is at a very high level, and they haven’t yet incorporated their beliefs about how their product is meant to fit into those particular models.

As a result, they’ll look at certain ratios, for example, the cost of acquisition compared to the lifetime value of the customer, and they’ll think that since everyone else is tracking this particular number, they’re going to track it too. They’re going to try to reach some magic ratio.

What they’re not doing is digging into their product and thinking about the value exchange between the user or customer and their product, and trying to understand how those key value moments link back. Obviously, you want to increase the lifetime value of your customer, but what’s your hypothesis or your bet for a more simplified way of looking at it? What’s your bet for how your particular strategy is going to contribute to that, to extend that lifetime value for customers? What’s the bet, what are you really banking on?

What’s fascinating when you pose these questions is that it’s the bridge between their business and these high level frameworks that makes sense on the surface. You understand the “it depends” part at the end of that blog post on a framework: it all depends on what you’re doing with your product, and how your product fits into that framework.