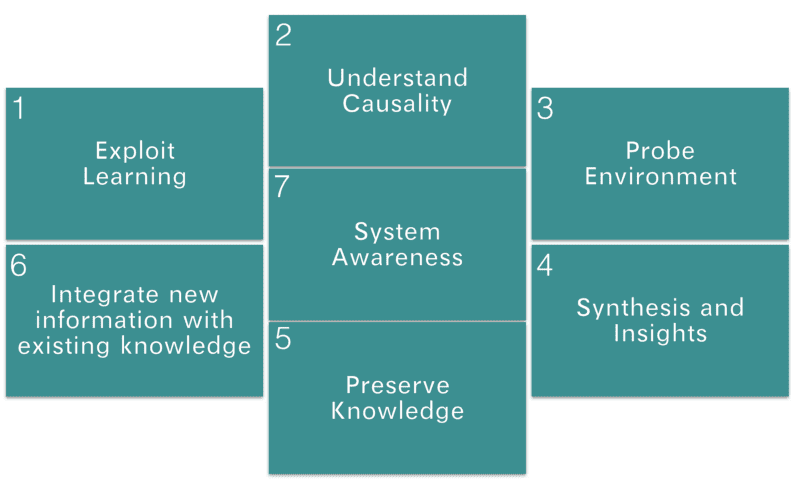

What is the right way to scale your company? How do you know whether a process is the right process? Here’s an idea … ask yourself whether the action you are considering will improve or harm your ability to do the following:

- Exploit learning quickly and effectively

- Understand causality between actions and responses

- Probe environment for new information

- Synthesize and draw insights from new information

- Preserve existing knowledge

- Integrate new information with existing knowledge

- Maintain and grow system awareness These items can apply to how we work, who we hire, what we build, who we target, how we structure our organization, and how we respond to change (among other things).

refers to the act of converting learning into value. That value might be external customer value, value to the organization, or value to the team/individual. Every action is an opportunity to learn, which is covered under #3.

A friend read a draft of this post, and remarked “you didn’t mention just plain old execution!” I countered by explaining that #1 can refer to exploiting existing knowledge (e.g. “we know what we need to know, and just need to execute”). I also asked how she knew that they were in an execute-only mode, and how she’d know when/if the situation had changed enough to warrant a new approach (#2, #3, #4, #6, #7)

System awareness (#7) is focused on systems thinking, sensing changes, and understanding the movement of information and energy inside systems. I see this is more of a “glue” for the other items, as it is important to understand that applying energy in one area tends to have an impact in another area (sometimes violent and unexpected). It also covers classification of the system (see the Cynefin framework to understand simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic systems), and how well we understand the fitness landscape for our current challenge.

Scaling up a company always involves some risk of loss. We make sacrifices in the hope that more cumulative energy will pass through the system. But when some of these capabilities are lacking, it is very easy to overshoot. For example, we might impose too much structure, dictate too much homogeneity, encourage too much specialization, or grow too quickly … and then get stuck trying to claw ourselves out of a hole. Why? We were too slow to sense the negative impact and/or our sense of the system lead us down the wrong path in the first place.

What happens when we boost or dampen these abilities? Consider these examples:

Spotify (the music service) is frequently cited as an example of how to “scale software development”. I’d argue that Spotify is an example of how a team of empowered agile coaches iterated on the scaling challenge, and helped the company resist numerous premature optimization traps. To copy it you would need to create a system conducive to that kind of reflection and experimentation, and the output might not represent what Spotify ended up doing.

When psychological safety is lacking, no one speaks up to smooth over conflicts within teams, which makes it hard to gauge overall system health. Failure is stigmatized, making it difficult to probe the environment for new information. Passionate individuals leave the company, bringing with them important situational knowledge. Layers of management emerge to smooth over the lack of trust, thereby making it harder to change course quickly.

Experience. A skilled product development team is more effective at exploiting information and avoiding architecting themselves into a corner. Experience in a domain lets you build on existing knowledge. You’ve “been there, done that” so you know where to find the signal in the noise when looking at data. Experience from an old domain applied to a new domain can have the opposite effect: close-mindedness, and resistance to learning new things.

Measurement Debt and Data Silos. Lack of data makes experimentation very difficult. Data silos impact system awareness, which encourages local optimization over global optimization. If the data is hard to get at, it makes it difficult to leverage historical knowledge.

Incremental Delivery and Cross-Functional Teams. We frequently probe the environment for new information, and can exploit these learnings quickly. Different perspectives drive interesting insights. Fewer handoffs means less signal loss.

A series of small, intuitive, pragmatic sacrifices can have a massive impact down the road. Once the structures, incentives, commitments, and dependencies are in place in a system, it can be very difficult to back out. This isn’t to say that all rules and structure are bad — they may be exactly what you need to battle a particular challenge (or to defend the seven capabilities) — but they are risky when too rigid.

Give this a try. Create a checklist based on the seven points at the top of the post. When you are considering making a change, ask if it will improve or hurt your ability to sense and respond.