Habits, Forcing Functions, Sense, and Response

If you boil down most of the software product development angst I see on Twitter (and in my own writing)… you end up talking about present bias.

Why are we cutting corners? Why are we chasing short-term gains of long term health? Why don’t we pay more attention to quality, if we know it is going to bite us in the ass?And that makes sense, because we’re human.

Present bias is the tendency to over-value immediate rewards at the expense of our long-term intentionSome other cognitive biases are important here as well: ambiguity effect (choose certain options over ambiguous options), status quo bias, illusion of control, bandwagon effect, anchoring, etc.

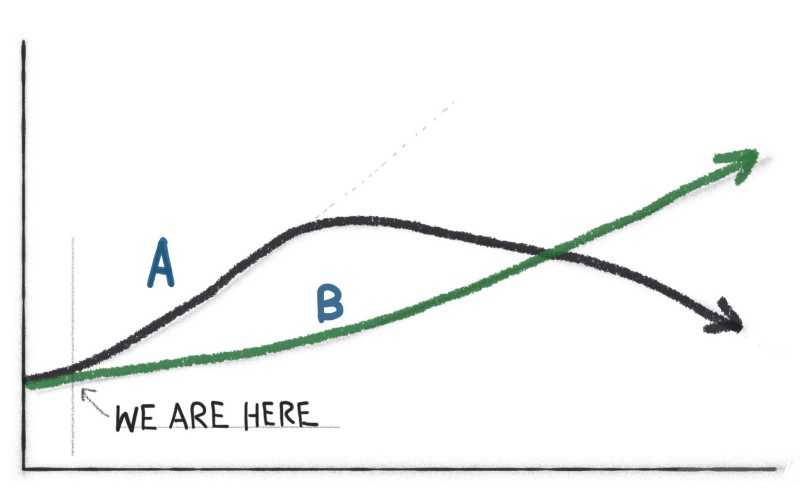

In this post I look at sense & respond, forcing functions, and present bias. How do we do things that hurt in the near term, but are good for us in the long term? How do we stay on the B path?

An apple a day…

Eating an apple every day is smart, especially if you eat the peel. It keeps the doctor away. But most of us don’t eat an apple every day. Why?

Exercising is smart. Luckily, it provides immediate tangible benefits. You feel good after taking a jog (after some adaptation and practice). Endurance exercise is mildly addictive. What if it wasn’t? Funny how quickly we forget what “being fit” feels like, and start to rationalize that we don’t have any time.

There’s a massive industry around personal “habit hacking”. The crux is figuring out how we can do things that don’t really make sense in the moment. This is an intensely human problem. I catch myself being totally hypocritical all the time. I’ll ask a team why they can’t focus on doing [some mildly uncomfortable thing with long term benefits] and I’ll be procrastinating on half of the important things in my life.

Quality and craft is an apple-a-day.

Now SWDEV. Focusing on quality in software will slow you down initially. The benefits take some time to materialize. Anyone who has seen a company wilt away, crippled by debt, knows this.

The lure of short-term gains is always strong. Doing the “right thing” is also humbling. It is humbling to sit there without all the answers. How do we test this? Why can’t we test this? Will I look stupid trying to pair with someone on this? How do I tell my boss it isn’t safe to ship this?

There are countless apple-a-day examples across any software product development org. Continuous improvement (like self-improvement) — allocating time to fix and improve things — is frequently an apple-a-day itself.

Switching gears, how do we tend to tackle present bias?

One approach is aggressive pre-optimization. You predict the future, and plan accordingly. You never even have problems, because you’ve planned all contingencies in advance. Tough to do!

We tend to either entirely dismiss, or entirely worship the ability to predict the future. There are well-worn patterns we can learn from (e.g. drift into failure, org entropy, product to commodity). It’s a mistake to ignore these thing and/or blindly accept them.

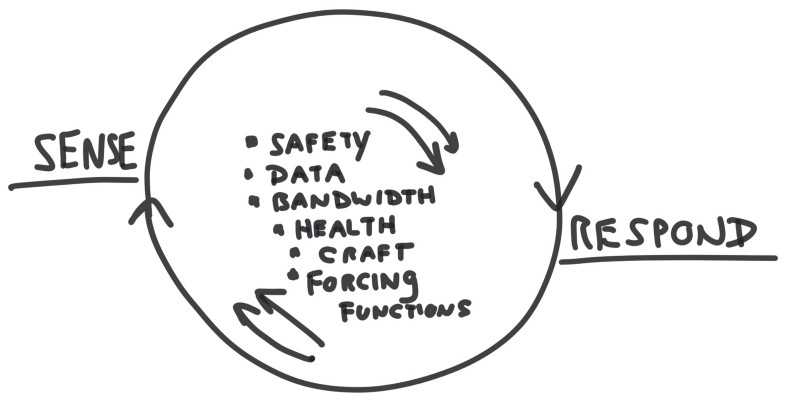

Another option: sense and respond, or “Waiting for problems to crop up, and then acting”. You need very sensitive radar to detect abnormalities, and you need the slack (and agility) to address problems when they crop up. If you have a pile of chronic issues “in queue”, you’ll start tripping over yourself. Awesome if you can pull sense/respond off.

At the highest end of sense/respond you have chaos engineering… perturbing the system to test it. You’re not waiting for a forcing function to trip. Instead, you’re triggering small failures/stressors to gauge how the system responds. This requires high safety. I know a company that intentionally causes chaos by shuffling its teams quarterly and letting developers/UX self assign to projects. Suffice to say, they’ve established deep safety.

Forcing functions as sensing tool. Use with care.

Chaos engineering is a type of forcing function. Effective forcing functions are often a tad counterintuitive. Forcing functions are your early-detection-system. They force you to pay attention.

Some are triggered — you hit a some threshold — and others encourage a regular habit (they “force” a habit and attention) when we might not normally take that action. Both cases force sensing and response.

Forcing functions are only as good as the actions they inspire. You risk your forcing functions inspiring dangerous things (a slip in quality, a drift into failure). Forcing functions w/o safety and transparency are volatile.

Working small makes logical sense. But it is not how we are intuitively wired. It’s tempting to get our cavities knocked out in one, painful, crappy dentist visit. When suggesting best technical practices, we often forget this. Working small is a form of forcing function. As with any forcing function, working small requires safety, support, habit-hacking, etc.

Sense and respond. Leverage and drag.

Anything that dampens (or enhances) your ability to sense and respond will dictate your approach. Craft, experience, data, psychological safety, etc. all provide leverage. Without these things you have drag. With drag, you’ll be chasing your tail.

There are teams who are awesome at sensing, but have no bandwidth (or skill, or autonomy)

There are teams who are awesome at sensing, but have no bandwidth (or skill, or autonomy)

to respond. There are others who are very execution focused, but lack sense-making abilities. And still others who are great at both…but in a different context.

“We just need the right people in the right roles” ignores that craft/experience alone will not solve your problems. If the whole system cannot sense and/or cannot respond … you’ll be left with frustrated high performers. “Oh the managers tell us when stuff is off” is overly optimistic. Managers will filter information and locally optimize by design.

So what can you do? Ask… “how can we increase leverage and decrease drag on our ability to sense and respond”. Think about how to make sense/respond frictionless. This is the velocity we should be most concerned about.

Forcing functions require a leap of faith.

Commit to forcing functions that don’t make 100% “sense”. You’re doing it right if 60% of people in your org say “I get it, but do we really need that now?”, or “that’ll never scale”, or “but that’s a bit uncomfortable”.

This is the leap of faith, but science and experience backs it up (cognitive bias throws us a little towards the other extreme). The nemesis is longer term and non-linear impacts.

Forcing functions alone will not solve your problems.

Forcing functions are your sensitive radar. But WITHOUT psychological safety, trust, transparency, room to maneuver, and craft … they’re dangerous. So care deeply about those things. Protect them with forcing functions! The worst thing that can happen is to sense all sorts of problems, but be too saddled with chronic health issues to do anything about it. Or to lack the autonomy and craft/experience required to act. That sucks!

FF Examples: regular pairing, WIP constraints, % allocation to refactoring, kill-feature quotas, all-hands retrospectives monthly, alarm bells if psychological safety measures fall, defect counts, lead time limits, any pull-based activity, regular chaos engineering, etc.

Riskier FFs include: OKRs, on-time delivery, etc. If your forcing functions are ALSO performance measures, bargaining chips, success measures, etc. — and people are asked to “set” them … there is even a greater burden for safety. Tread carefully.

Good example: You could view sales quotes as a forcing function. Miss the goal, and that inspires a reassessment of the sales strategy, tweaking, and responding. If only … we all know what happens when the sales quota is missed. You can see the problem here. Avoid at all costs.

To hack daily habits, you need people to believe you.

Finally, like exercise and eating apples, you need to hack the daily habits. Make sure you pay attention to autonomy, mastery, and purpose (Pink). The challenge is that some forcing functions feel, on the surface, like they restrict autonomy, and challenge mastery. Pairing is a good example. You have to tell a better story.

The same goes for “cue, a routine, and a reward” (Habit Loop, Duhigg). A critical factor is BELIEF. You need need a persuasive story about the “bet” the company is making on quality (or safety, or resilience). These aren’t personal habits like stopping smoking. They company can’t ask front-liners for discipline while exhibiting poor self-control. So…congruence and belief, and then hack the cues, routines, and rewards. Even better, let the teams do their own hacking.

The story matters. Your organization has to take pride in its various sense-making mechanisms (including forcing functions). Your teams have to have faith that these things are in place to help, and not hurt.

In summary…

So, with that … you need sensing, responding, and leverage. There’s no silver bullet to defeat the present bias. It may require some blind faith. We can hack the system in various ways: get better at sensing change, act on those signals more effectively, and perturb the system. Don’t discount experience: patterns matter. Knowing that X tends to happen to companies in Y context is a data point. Finally, forcing functions are powerful, but only when used safely.