http://www.grit.com/animals/electric-fencing-basicsYour team ships a new feature. Something is not right.

You’re worried about the test and monitoring/analytics coverage. The developers weren’t able to refactor some crappy code, which made things take longer. The uptake isn’t what you expected, and it looks like users are struggling with the workflow (but you having trouble parsing the details, because of the poor monitoring). It feels shoddy, and as someone who cares about doing good work this bothers you. The ensuing success theater — with sales and marketing in full pitch and sell mode — just makes things worse. It starts to gnaw on you and you find yourself being uncharacteristically testy. Someone has to say something, right?

Tactfully, you mention your concerns during a 1:1 chat with a manager. It doesn’t go well. She responds:

We can’t be perfectionists! We have to get stuff out there and be Agile. Sales is killing it with this! Users might be struggling, but let’s be honest, they’re not our customers. They don’t pay our bills. We also have a great support team to smooth things over. All I’m asking here is that you focus on what you can control, and on being a team player. I’ve noticed you being more negative lately. I bet the team doesn’t appreciate that! They worked hard on this. They might think you’re undermining their work. Be careful …Biting your lip, you mull things over in your mind. That’s a lot to process. The conversation feels manipulative on many levels, but perhaps you’re not seeing something. You know that’s not the definition of Agility, but that’s the least of your concerns. The questions flow: Was the work in vain? Am I just naive? Are my standards too high? Is it better to just go with the flow? Maybe she knows something I don’t know?

You think about your significant other and your apartment in the Bay. The company isn’t burning, and you’ll likely have this job for at least the next couple years. It is decently fun, the people are nice, and there’s a chance things might work out.

Does she know something you don’t know? That last question inspires you:

Thanks for the, err, advice. I appreciate it. I understand that at times we need to cut corners. It would just help, to, you know, feel like there was a good reason we were cutting those corners. Like there was an upside. Or at least to be transparent about the risks we’re taking. We’re making a bet that it doesn’t matter, for now. We’re making a bet that we don’t need to do our best work, and that this will pay off in the future. Let’s at least make that explicit. I’m willing to roll with it. How will we know when it is the right/wrong bet to make?There’s a pause. Now put yourself in the shoes of the manager. Someone is asking her to:

- admit that the best work is not happening

- admit that this is impacting someone who cares, and

- be explicit about risk, and agree to be called out on her decisions at some point in the future. And all the while she is likely dealing with the same cognitive dissonance from her boss, and her boss’s boss.

It’s like asking someone to acknowledge that:

- smoking is not the best choice

- second hand smoke is harmful to friends and family

- they’re making a calculated decision that not quitting now will serve some future good for everyone Based on my chats with my mom (a smoker of 60 years), that doesn’t work. The response is predictable: defensive, dismissive, mildly threatening, and brief. Meeting (or lunch with mom) over.

I’ve fallen for this trap dozens of times. It ALMOST NEVER works. You’re not going to get the clarity you’re hoping for. Sure you’ll get clarity about everything else — what’s in the backlog, sales numbers, the fancy methodology you’ll be adopting, your managers plans, etc. — but you won’t get the level of transparency and vulnerability you desire. Larman’s Laws of Organizational Behavior gives us some clues. The third point especially:

any change initiative will be derided as “purist”, “theoretical”, “revolutionary”, “religion”, and “needing pragmatic customization for local concerns” — which deflects from addressing weaknesses and manager/specialist status quo.Now, it is easy to make this about middle management. Often, however, they are merely caught in the middle. They’d love to have good answers for you, but the strategy they’re getting is equally as obtuse. To Craig Larman’s point, handling these wicked problems typically triggers a litany of arguments meant to basically shut you up and calm the cognitive dissonance (theirs and yours). These talks literally hurt the manager’s head and make them feel helpless and out of control.

So what do you do as someone who cares and wants to do great work?

To fight this battle, you’re going to need to be quiet and carefully observe.

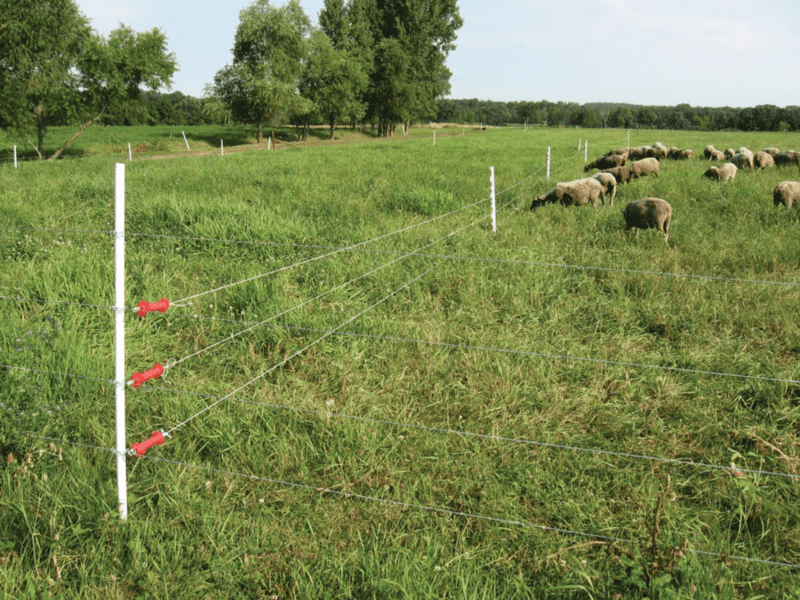

- Where is the invisible border management has created around continuous improvement? I like to call this the electric fence: the border that seems to trigger the defensive reaction. Even organizations that pride themselves on “radical candor” have these fences scattered around

- What issues come up over and over, but somehow always trigger the localized “pragmatic” response? Check annual surveys, retros, and post-mortems. What do people keep bringing up, but simply stop complaining about?

- What is your organization optimized for at the moment? Draw out the system

- What is the real culture as evidenced by actions, not words? After you’ve observed for a while, ask yourself the hard question. Are you ever going to do your best work in your current role? Change rarely happens because one person goes on a mission. Canaries die (that’s the point). Is this a place where you can be challenged, and feel like you’re doing great work?

Still willing to give this place a chance?.

- Don’t waste time having conversations with people who will be paralyzed by discomfort. Instead, focus on how to create safe situations where people can talk about this stuff without tripping the electric fence and causing defensiveness. Achieve that first, then have the conversations that matter. If you find yourself in a spokesperson role without other advocates at your side, you are likely going to fail

- Visualize impacts, don’t talk about impacts with generalities. Basically … show, don’t tell

- Talk about your own needs (e.g. “I have a need for more rigor here”) vs. grafting your needs onto the rest of the team, or speaking generally about a fucked up situation. Speaking generally fires the stress response

- Consider that we often focus on the corners we cut, because there is nothing positive happening to counteract that crappy feeling. These are two distinct problems: 1) things are awesome because we’re cutting corners, but we’ll pay for it later, and 2) we are cutting corners now, and things are not awesome. Both are challenging, and attract a different response from those on the front-lines. In most cases, someone is aware that corners are being cut. The danger of things being awesome, is that we discount those cut-corners altogether. When we’re craving awesome, we make up all sorts of excuses why it’s necessary to cut corners (without admitting that we’re in this mess because of prior corners cut). So both are dangerous.

- Try to take the emotional sting out of the word “bet” and use it! Bet is an interesting word. In a safe to fail environment we are free to make bets, including those that might involve cutting some corners. In a culture of fear, the idea that you’re betting the company’s money by doing less-than-great work is not to be discussed. Socialize the word “bet” in a safe way so that it has the potential for changing the mindset

- Set an example. You aren’t going to get that manager to be transparent about their calculus. But you can discuss your own bets, and be humble when things don’t pan out The big point here is that in these situations it is not just about speaking up. The reaction you trigger can often circumvent your cause. By all means encourage an environment where uncomfortable and challenging discussions can happen. Encourage safety. But realize that candor alone wont destroy those electric fences. That may take more time, and more strategy. Or you simply finding another place to work.