Update: I created a video here to accompany this post

I’ve been under some fire lately for suggesting that teams forego fixed-length sprints. The pushback is that fixed-length sprints are more appropriate for less experienced teams, and what is known as “continuous flow” is a better fit for high-performing teams.

In this post, I am going to try to get to the heart of the matter by discussing variability, meaningful goals, and “independent and valuable” vs. “small and testable”.

I hope to show that there are a spectrum of approaches that can be used in tandem, and that even less-experienced teams can benefit from experimenting with variable-sized batches, flow, pull, AND fixed-cadences. This isn’t an either/or question.

Variability

Sprints get interrupted for a bunch of reasons: addressing production issues, sick days, unplanned days off, random company meetings, issues with tooling/pipelines, etc. Coupled with the unpredictable nature of “the work”, and the unpredictable nature of “the workers”, and you have a lot that can “go wrong”. On any given sprint, only so much is within our control (though we can work hard to remove impediments over time).

This is complicated further by dependencies. “Self-organizing” and “cross-functional” are good in theory, but few teams — especially teams starting out — have that level of autonomy. Handoffs to QA, shared UX, shared Ops, compliance, customer schedules, stakeholder schedules … none of these things are ideal, but they happen (way more often than we’d like).

The point here is that in the real world things are messy. There is a ton of variability — even in a short sprint — and teams are rarely acting in a vacuum. This can make forecasting sprints and setting “sprint goals” extremely difficult. For beginner and experienced teams alike — especially with dependencies — this becomes a Sisyphean ordeal. One answer is to make the sprint even shorter…and I’ll get to that below.

Meaningful Goals and Product Increments

Meaningful goals don’t always come in the same, neat, N-week/day box. Sure you can artificially “pad” a goal to make it bigger, and shrink a goal to make it smaller, but sometimes you’ll need three days (or three hours) to validate an important assumption, and sometimes you’ll need fifteen days to stitch together a complex workflow. That’s just how it is. I often see teams cook up “kind of fake” (their words)

Meaningful goals don’t always come in the same, neat, N-week/day box. Sure you can artificially “pad” a goal to make it bigger, and shrink a goal to make it smaller, but sometimes you’ll need three days (or three hours) to validate an important assumption, and sometimes you’ll need fifteen days to stitch together a complex workflow. That’s just how it is. I often see teams cook up “kind of fake” (their words)

goals due to the constraints of the timebox.

Since all the stories are independent, even “kind of fake” goals will be fine…right? Value is still delivered, even if the team doesn’t achieve “the goal”. Hmmm. That would be the case if each and every story was independent with respect to the Sprint goal. However…

There is a spectrum here when it comes to the “Independent” and “Valuable” in INVEST. A story might be independent and valuable from the standpoint of learning, and helping a user along a workflow, but not independent from the standpoint of a meaningful goal. This is where the I and V can come in conflict with the Small and Testable. It would be wonderful if every user story represented an end-to-end, outcome-oriented user goal (or business goal), but it often doesn’t work out that way.

The Scrum Guide describes the fixed-length sprint as a fixed-length project of sorts:

Each Sprint may be considered a project with no more than a one-month horizon. Like projects, Sprints are used to accomplish something. Each Sprint has a goal of what is to be built, a design and flexible plan that will guide building it, the work, and the resultant product increment.Operative here is the idea of “accomplishing something”, which is great in theory. What happens in reality, however, is that teams start by asking “how much can we get done in [the sprint duration]”. They “fill” the sprint, instead of starting from a meaningful “resultant product increment” backwards. The argument is that 1) if everything is valuable and independent, 2) everything is ordered, 3) there’s a history of velocity, and 4) there’s transparency… well, it will all work out, and if some stuff gets “left over” at the end…no big deal.

What happens next in practice? A sprint ends without a resultant product increment (or an increment which doesn’t really hit the goal), there’s a lot of song and dance while the stories are “punted” into the next sprint, and a new goal — a weird amalgam of the prior goal, and a new goal — is set.

Working Small vs. “Value”

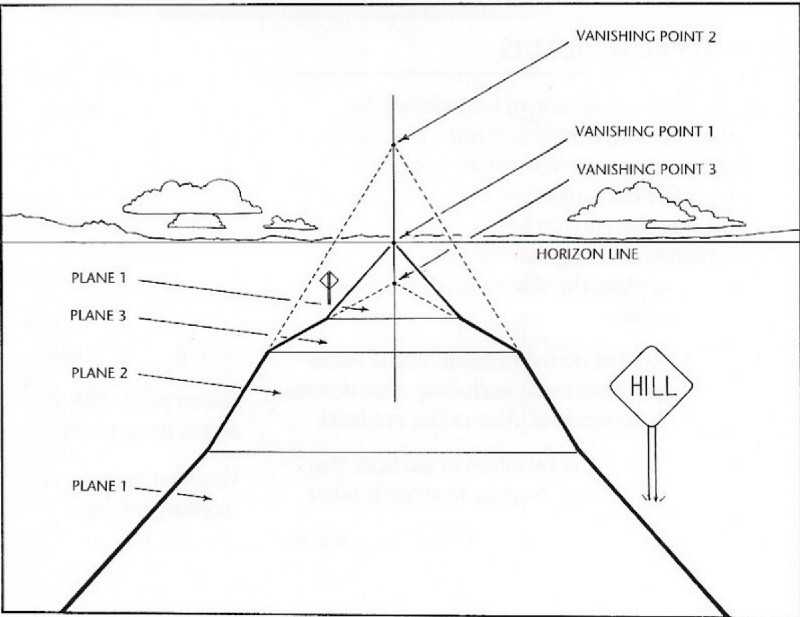

Again there is a tension between the benefits of working small — small stories, integrating and demoing frequently, and delivering into production frequently — and delivering value (at different scales and resolutions). Short sprints are extremely valuable as they help us inspect/adapt/integrate/reality check more frequently. But you will not always be able to fit meaningful goals into that timebox. Which puts pressure on teams to extend the timebox…which results in sprints that are too long.

Here’s my take. You’re talking about two different cadences: the meaningful goals (the valuable product increments), AND the valuable, tight, frequent feedback loops…which are super valuable, but not the same kind of value. There is no way that a single, fixed iteration length can accommodate the variety of meaningful goals. Sometimes we’re doing a bunch of small optimizations. Sometimes we are testing the core viability of a new product. Sometimes we’re pivoting day-to-day.

Summary So Far

To summarize.

- We encounter a ton of variability (including variability far outside of our control).

- Our meaningful goals often don’t line up with our independent and valuable stories. Both are important.

- Meaningful goals don’t all come in the same size/shape

- There are amazing benefits to “working small”, and there are amazing benefits to having a meaningful (and flexible) goal.

- There are amazing benefits to inspecting and adapting frequently.

Hybrid Scenario

How might a team address these challenges. I’ll use the working agreements from an actual team:

The team:

- has a prioritized list of meaningful goals (the backlog is described in goals, not individual stories)

- sets meaningful goals that take between 1 day and 30 days (team agrees on a max length of 30 days, after which the whole goal is reassessed)

- addresses these goals serially on a pull basis (one at a time, starting a goal only after the last goal has been accomplished)

- visualizes the dependencies as they are, and visualizes the impact of unplanned interruptions (e.g. production issues)

- forecasts duration for “meaningful goals” using historical data (especially useful if there is a lot of noise, interruptions, dependencies, etc.)

- addresses planning for goals on a just-in-time basis (story maps, etc.)

- caps individual story sizes to <3 days with frequent pairing

- meets weekly to conduct a retrospective and discuss progress

- gets new work into production behind a feature flag weekly (automated, weekly)

- conducts demos and usability testing whenever possible (using staging and/or production) This is a hybrid. Some things happen weekly, some things happen just-in-time, and some things happen in automated batches and “whenever possible” (e.g. the weekly release train and the frequent testing).

Why? Benefits…

What is happening here? Fixed-length sprints are a game of sorts. You play the game, and there are benefits to playing the game. The team can only go so far astray, and if you do it “by the book” you’ll end up with a releasable product increment at the end of each sprint. If you fall short, well, everything was independent anyways (hopefully). Or you just punt things to the next sprint.

There is skill involved with making them work. But honestly, there is also a ton of luck at play. They can also — in some cases — obscure what is actually going on, especially when you’re part of a larger system, have dependencies, and are responsible for a production system.

The model I shared above enjoys some of the elements from fixed-length sprints. But instead of the song and dance at the end of each sprint, the team focuses on the goals that matter. At the same time — and this is important — they also commit to work small, and frequently inspect, adapt, and test. When they’re hit with unexpected variability, they roll with with it and work on continuous improvement to minimize those interruptions.

Work Small + Work Meaningfully + Inspect/Adapt.

In Closing

I’m not saying fixed-length sprints are bad. They may work for you. Indeed, let’s say you decided to do a monthly release of “something new”. Well, there is your fixed-increment. But one month is a long time! So you would still benefit from working small, retro-ing weekly, and perhaps demoing/releasing features just in time (as often as possible) to some % of customers.

My point is that it isn’t either or. You should be aware that not all teams do Scrum by the book with fixed-length sprints, retros at the end of each sprint, and planning on a cadence, etc. There is a huge spectrum of approaches that might work for you.

Whatever you do:

- Visualize your work as it really happens

- Inspect and adapt

- Work small

- Integrate and inspect/adapt frequently

- And do meaningful/valuable work Love this mission statement created by a team: