With Matt Barcomb, and editing help from Morgan Maccherone

A few weeks ago, my friend Matt Barcomb

A few weeks ago, my friend Matt Barcomb

asked this question via Twitter:

It got me thinking. Over the years I have witnessed countless efforts to fix team-level issues, while seemingly ignoring the broader organizational challenges. Teams struggle to do what they can, but meanwhile bump up against the more global bottleneck. It’s all about trying to fix problem teams instead of tackling the the bigger problem.

I reached out to Matt to mull this over, and we decided to write a brief post about the topic. We explored a couple questions:

- Why does change at the team level usually not work?

- So who is responsible for addressing organizational dysfunction and facilitating change?

- Where do we start?

- How do we decide what to change?

- How will we measure improvement?

- How do you keep people motivated and make change stick?

Why does change at the team level usually not work?

We need systemic change around and between teams.

Unfortunately, many improvement efforts and even organizational “transformations” really only focus on the team level. Most requests for “scaling” are a veiled request for standardization and spreading “best practices.” While this may leave the campground cleaner, major or permanent change is less likely due to the need for environmental, systemic change around and between the teams.

Dysfunction beyond the the team level is more difficult to see.

One reason that change is typically focused at the team level is because much of the upstream dysfunction is a lot harder to see. The dysfunction doesn’t visibly manifest itself until it snowballs into an “under producing” delivery team (where team-level issues are seemingly easier to measure).

Change is risky. The status quo is safe.

Another reason is that often, for management, there is too much risk and too little reward to bring in change. If it goes well, there probably isn’t much of an upside (versus what you’d get anyhow by performing well in the current status quo). But if the change goes poorly, you’re the person that wasted all that time and money and delayed everyone else’s work and made the customers angry. No thanks! Even if this risk/reward problem is less obvious, it’s still adding pressure to our natural human biases that make it difficult to see ourselves as part of the problem. It’s hard for any level of management to want to change itself. The problem is always “them” — and “they” are always downstream.

So who is responsible for addressing organizational dysfunction and facilitating change?

Who is involved?

Understanding that team level change will rarely result in systemic change, it is important to consider who is responsible for initiating the change, and where we should start first. Of course, who is involved and who owns the change should depend on what is changing. It’s not simply management’s job to make it happen.

Use “real work”, but involve everyone who depends on the change.

Using real work to facilitate a change solves the issues of ownership, advocacy, and involvement. The people involved in the work are the right people to involve in the change. By “involved” I am not only referring to the individual team that “does” the work. Of course they are going to be involved. But there is an extended network of sponsors, owners, managers, and even customers who need to be part of the initiative. Anyone who depends on the change, should be involved in the change.

Change that spans silos and structures is hard!

However, simply stating who should be involved in change is much easier than actually involving them. In many cases, there is no official “process” to handle issues with a global impact and shared responsibility or ownership. It’s expected that the managers will coordinate among themselves to fix the problem, but they’re typically too busy just keeping their individual ships afloat. The tendency, therefore, is to quarantine the problem with a particular department (e.g. “operations owns fixing that”) instead of figuring out how to get all hands on deck. The managers also 1) heavily identify with being an information conduit between the front-line teams and upper management, and 2) have other, often competing agendas. In short, information doesn’t flow and structural challenges hinder the response.

Where do we start?

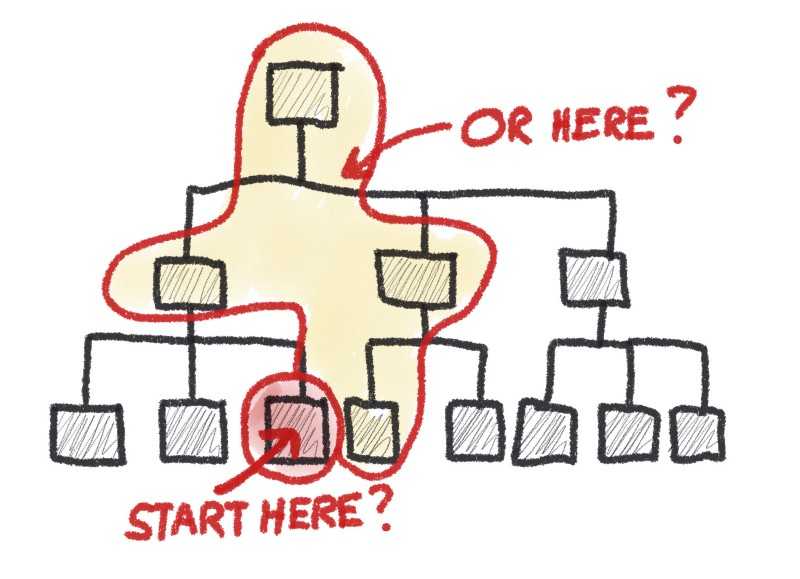

Interest over impact.

All that being said, change has to start somewhere. At the beginning of a larger scale change effort, it may be useful to follow interest over impact. The goal being to build momentum, get folks excited, and grow trust and confidence. So in terms of picking a starting point to focus on, anywhere of interest is one approach.

Start in the middle, where there is already momentum.

If you’re looking for the most impactful place to start, I would begin by closely examining your organization’s structure, funding models, and incentives (both implicit and explicit) and explore how they amplify or dampen your organization’s vision and mission. In my experience, most root causes link back to these things. Unfortunately, this is rarely the best starting point because these areas require a great deal of internal agency to change.

Most optimally, I’ve found it useful to choose a starting point at a mid-organization level that is seeking to switch paradigms with executive support. An example of this might be an organization that realizes it has been sales-led and is now seeking to become product-led. These kinds of starting points typically have greater impact than simple team optimizations even though they will typically require team-level improvements as well. Mid-level change also puts you in a better position to measure or influence up and out and possibly address some of the more fundamental issues such as structure, incentives and funding models.

How do we decide what to change?

Distinguishing between everyday and chronic problems is difficult.

After figuring out the best starting place for change, it is beneficial to ask “are all problems worth tackling?” Are there such things as everyday problems that will just go away on their own? If so, how can you tell them apart from chronic, systemic issues? There is no easy way to tell the difference between an everyday and chronic problem. This creates the obvious problem of not being able to know what problems are worth tackling.

Use the “simple things” as a starting point.

The task becomes easier if you consider all the problems you experience and use them as a sensing mechanism to detect better, deeper problems. You can even start keeping track of some simple things that can help you determine or validate if a problem is worth solving. I bet you already do a lot of this. How often and when does this happen? Does anyone else experience this problem? Why does it really bother me? Typically, people already have a sense of the repetitive, tedious things or the impactful things that happen on occasion. At this point, I would simply suggest following the scientific method in a progressive and exploratory way.

Look for leverage. Be thrifty when purchasing information.

Basically, make sure you understand the cost of obtaining information about the problem and the value of the decision or action you will take. You’ll want to “spend” less initially and you’ll get lower quality information, but that should help guide you directionally until you decide it’s time to fully invest in solving the problem. Spending more time upfront will allow you to get to the core issues, address them successfully, and hopefully fix the dysfunction.

How will we measure improvement?

All improvement is measurable.

No matter where you start, it’s important to be able to have a sense of how you’re doing. Personally, I believe all improvement is measurable. If we can have a sense that something isn’t great then we should be able to say what “better” would look like (as well as how we would tell). While much of this is specific to context, I typically try to quantify impediments and their impacts, value to customers, well-being of employees and intentionality and speed of decisions.

Measurement is an iterative process.

When it comes to measurement, one of the key anti patterns I’ve noticed is not treating measurement itself as an iterative process. When you associate “success” with picking the “right metric,” and then give the team one chance to pull that off perfectly during a kickoff — you’re bound to get it wrong. I’ve been involved in countless meetings like this. The team arrives excited to jump in, someone mentions measurement, and then energy gets drained from the room as people debate the usefulness of certain metrics.

We tend to overthink these efforts. In most cases we aren’t detecting gravitational waves. Take a step back and ask…

- What is the baseline here? What is going on? What are we observing?

- What is the impact to the business?

- What decisions do we have to make?

- What must we learn to make those decisions easier?

- How much are we willing to spend to “buy” that information?

- What are a couple experiments we can run to capture that information? And, no matter what, make it safe for the team to “just start” with the help of a coach. The first step might be timeboxing a day or two of research and having pairs present back to the team. The right measurements tend to emerge. We iterate as we learn.

How do you keep people motivated and make change stick?

Visualize your continuous improvement efforts.

One of the highest leverage things you can do is to visualize and socialize the continuous improvement work. This might involve one or more “learning/experiment” kanban boards, biweekly team talks to the whole product development team, health metrics on your team-wide dashboards, and celebrating the small wins. Make this part of everyone’s day job. And acknowledge it may feel new, and therefore difficult.

Continuous improvement takes practice.

In my experience, it is tempting to bombard teams with theory and training before launching into a continuous improvement effort. What we miss here is the learning phase. It can take multiple cycles before (potentially adhoc) teams become comfortable with stating assumptions, designing experiments, and then closing the loop with the rest of the org. Trying to be perfect on the first go is a recipe for disappointment. This is where having a couple trained facilitators and coaches can go a long way.

Set conservative goals. Limit Change in Process.

Finally, it is important to set conservative goals. As with your product development efforts, you are looking for a flow of learning. It is tempting to tackle too many problems at once, and then swamp the organization with prescriptive improvement projects. You also tend to run into a strange dichotomy between “the stuff teams were doing anyway” and “the new stuff we have to coordinate across teams.” These two streams run in parallel, and unless you’re careful, you can overwhelm individuals and teams who are involved in both efforts. Instead, treat this as a single backlog. A good forcing function here is to apply a forcing function like a WIP limit, a regular update with only so many slots, or a “single priority” rule.

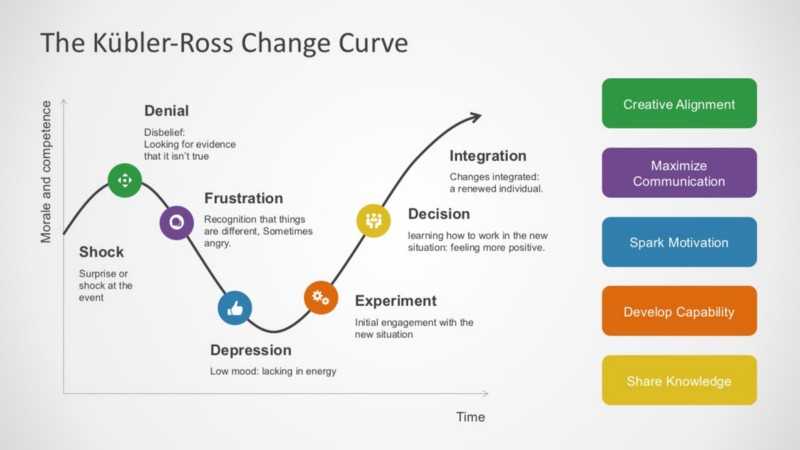

Dampening the ups and downs.

All of these recommendations tend to become much more obvious when we look at the more emotional effects of change on employees. The Kübler-Ross change curve, which you may be familiar with as “the five stages of grief,” has been used extensively to describe and understand the emotional changes that employees undergo during and after organizational change.

* Involving employees in the initial processes of deciding what to change helps diminish the shock and denial phases.

* Involving employees in the initial processes of deciding what to change helps diminish the shock and denial phases.

- Visualizing improvement, setting reasonable and attainable goals, and starting with interested employees are all great ways of neutralizing the frustration and depression employees may experience.

- The experiment stage goes hand-in-hand with an iterative and collaborative approach to discovering the right metrics, and figure out what “works”.

- And of course, all of this becomes worth it if you are actually addressing the root cause of the organizational dysfunction.

Final Thoughts

All companies have problems. The best companies have fewer chronic issues.

I find it useful to think of continuous improvement as “keeping the body healthy.” All companies have problems. The best companies don’t let too many problems become chronic. They bounce back. Injuries are detected quickly. They aren’t afraid to get scratched up a bit, because they know they heal up quickly.

If you’re in a situation with too many chronic issues, it can be nearly impossible to fix anything. You end up having the same conversations over and over. Problems overlap and complicate efforts. Nothing works, nothing changes, and your team beats themselves up. One of the hardest things to face is when the “big serious issue” you’ve been rallying to fix, is nowhere near the most serious problem the organization has to contend with.

The tipping point and weak signals.

The message here for startups and smaller companies is that you have to think about the health of the system, because there is a tipping point beyond which repair is extremely difficult. This is an extremely interesting measurement challenge, because the signals can be weak at first. Some potentially useful health metrics might include employee retention, stress and anxiety levels, lead time, measuring flow-state, and analyzing qualitative “stories” looking for outliers.

What works?

In general, successful, larger scale continuous improvement efforts tend to do the following:

- Directly involve the people who are impacted by the issue

- Directly involve the people who understand the problem space, and solution space (technology, process, data, systems, dynamics)

- Result in immediate committed action items (instead of committee forming)

- Address the issue as “business as usual” (part of existing funding, workflow, project management, and reporting structures)

- Displace work and other priorities (instead of just adding to the workload)

- Embrace an experimental mindset. The teams fall in love with fixing the problem, and not advancing specific solutions Number four is critical for addressing a common dynamic whereby managers are consumed by the day to day, and simply don’t have time to focus on “extra” continuous improvement work. As with most things, there is no silver bullet. You have to put in the time — write the tickets, have the meetings, deliver and test change, set improvement goals, and still leave at a reasonable time each day. Given the nonlinear nature of impediments — they start benign, and then suddenly overwhelm the team — you often can’t wait for the problem to “trend.” Prevention, without premature optimization, is the best medicine.

Wrapping up.

In conclusion, change, especially that which must occur at an organization level, is extremely difficult. However, if you spend the time upfront figuring out the where, what, who, and why, your efforts will generally be more successful and therefore, more rewarding.