Lately I’ve been fascinated by the interplay between goal setting, accountability, commitment, trust, safety, and coherence.

A ways back I started to write a fiction book about software product development. That futile effort involved a lot of dialogue writing. Today, I found myself reading through these fictional — but highly inspired by real life (they’ve happened) — conversations. I didn’t realize it at the time, but these themes (goals, accountability, etc.) were woven into almost every exchange.

There are no answers or how-tos in this post. I apologize. Instead, I wanted to dig into the complexity of this from many different perspectives.

Here are a couple snippets…

Manager

I’m trying to get the best out of people. Sometimes that means setting challenging, maybe impossible, goals, and seeing what happens. If you don’t try, how will you ever know what is possible?#### Individual Contributor and Manager at Retrospective

Individual Contributor: The organization is so broken…politics, always changing priorities, no help from other teams, and silos. We talk about blockers at EVERY retrospective, and nothing ever happens. We don’t control any of this stuff, and have very, very little influence. How many times do we need to complain about Jenkins? How many times do we need to ask for the right tools, training, and time to learn? So you know what? I’m going to stop mentioning it, and just lay low. Manager: But we need to do our best with what we have! I agree things are not perfect, but that doesn’t mean we can slack. How can we get creative here? What can we do?#### Engineering Manager

Here’s the deal…you own the problem and the priorities, and we own the solution. You tell us what — that’s your job — we worry about how. Arbitrary deadlines way off in the future would be crazy for us to commit to. What we can commit to is doing a small number of small things in a short period of time — the sprint — as long as you commit to being available to provide feedback. You do your part, we do our part. That’s how you build trust. And frankly, that’s how we defend ourselves from the insanity of the business. We both know how crazy things are.#### Software Developer

He’s totally slacking, and no one will call him out on it! When he does work, it disrupts everyone, and we’re all responsible for cleaning up the mess! But we can’t call him out because he’s friend with [some executive] and has been here for a long time. Plus, he’s an expert in [some critical component]…so we’re stuck.#### Senior Software Developer

I’m going to call the kettle black. Developers today are lazy as shit. They’re on Slack all day. They sit around and complain about meetings, estimates, and deadlines, but trust me….they’ve never seen how bad it can be. Things are EASY these days in comparison. The tools are amazing. What you are really hearing is stubbornness, insecurity, and a fear of being put on the spot…to being held to account for something. I used to think that management was the problem. I’ve changed my mind…I think developers are just overpaid kids. How can they expect to be respected? And then they go on and on about Amazon and Google. Trust me, I’ve worked at Google…they wouldn’t last a day if they acted like that. Talk about pressure-cookers and a no-bullshit approach to goals.#### Interaction Designer

I love my manager. It is rare to find this, but she is the perfect mix of understanding, listening, and also calling me on my bullshit. I genuinely think that she cares. When [some person] left, she gave him a great recommendation and even helped him network. At our first meeting, she asked about what I should hold her accountable to. It was like a two-way contract of sorts. There were times when I slacked, and I knew I was breaking my side of the bargain. And there was one time she got super busy and distracted, and she apologized and figured out how to improve.#### Manager

How am I supposed to performance manage unless people unless they have goals, make estimates, and make commitments? “Just do your best” is not good enough! I can’t point to something invisible and say “good job!” Or “you aren’t meeting expectations!” When it comes to “the problems”, no one knows what is going on, to be honest. Everyone has a different perspective. So we need a process in place to figure that out. The best outcome would be to absolve the team of blame here! But we need proof.#### Software Developer

Watching [the CEO] get up there and talk about the stuff that didn’t work out — and what we learned from it — was super inspiring. I know that shit happens, and we all make mistakes…so it was cool to see someone I really respect admit their mistakes. That discussion he had with the customer…I don’t envy that. That takes some serious skills and experience.Software Developer

It is totally unfair. There is such gross incompetence on the executive level. But who holds them accountable? When they fluff up the numbers, they are actually rewarded. No one checks to see if they were “right”. We’re told that the deadline is “just rough”, and we miss it…and shit hits the fan. The situation is SO hypocritical.### Some Observations

- Trust and safety is so damn important. It makes so much possible, and is so difficult to regain when things go south. When there’s trust (and safety), we are able to invite all sorts of more challenging interactions into the equation. Consider the message we send to a team when we impose a process meant to “root out” some sort of bad behavior or slacking. It conveys: “I don’t trust you”. Trust and safety are internally-generated intangible assets, so they don’t get recorded on the balance sheet…which both makes absolute sense, and is crazy at the same time.

- We among the individual contributor set tend to demonize words like accountability, commitment, predictability, ownership, and responsibility…mostly because we perceive them to run in a single direction (top — > down). Most of us have also seen these words repeatedly abused over the years (typically in conjunction with estimates, goals, etc.)…so much so that they lose any positive connotation. But can systems thrive without a commitment to trust and safety, to teamwork, and to respect? Prepend the word “mutual” before accountability and commitment…how does that change our perspective? Are we too jaded to imagine mutually beneficial, mutually committed, and mutual accountable work situations?

- “The work” is often treated as the primary currency of accountability and commitment. Why? It is relatively tangible. Focusing on “the work” also reinforces the desire for autonomy in terms of how to finish the work (“you tell us the what, we decide the how”). But… “the work” is only one part of the puzzle. Who is responsible for the health of the system surrounding “the work”? Management? Leaders? Or everyone? If work is the first-class accountability object, what does that say about how the org prioritizes the “other stuff” (like safety, support, growth)?

- Along those lines, how to we handle the case where so much variability and unpredictability surrounds “the work”? And what happens when people are incentivized to deliver exactly what they promised to deliver…even if it is the wrong thing to deliver? Is under-promise / over-deliver what we actually want? Maybe variability is our constant, and “doing your best” is all we can do given the context.

- Can managers serve multiple masters? One view of management is that it is in “support” of their teams (coach, facilitator, mentor). Another view is that managers are there to literally extract the “right work” out of teams. How is “accountability” and “responsibility” viewed in both models?

- Some cultures are considered “difficult” but they are also highly predictable. Employees know what they are getting into. Expectations are extremely high, but are “predictably high” and explicit. Employees often describe good managers as being “very tough, but fair”. There’s strife between departments, but people know “what to expect”. What’s going on here? Is it really coherence we crave when we voluntarily agree to take a particular job?

- No one likes being held “accountable” for something they cannot fully control. It causes all sorts of cognitive dissonance, hedging, and fear. This is one of the big blockers when it comes to having a team commit to an outcome (over individual “commitments”).

- There are always problems…especially in rapid changing landscapes. Meaning that it is always possible to point at something and say “that is fucked up”. That said, there are varying levels of fuck-upped-ness, and different people have different needs for coherence, trust, and support. When I talk to people who have stuck around in their current companies for >5 years, I tend to hear that there are indeed problems, but that in general most things work themselves out.

- What do we do when “root cause” lands at the human condition?

- Process frequently serves as a trust and safety proxy, while simultaneously introducing drag, and amplifying mistrust and toxicity. On the flip side, some process serves as a “contract” from which to build trust from a place a distrust. Take a look at a framework like Scrum. Consider the fears, aspirations, and worldview baked into its design. Consider whether it embodies a chip on the shoulder…developers who feel untrusted and constantly blamed. When Scrum reveals “the problem”, what dictates whether the positive or negative path emerges?

- We have incredibly sensitive coherence radars when it comes to external things (the company being fucked up, and behavior inconsistent). We perceive ourselves to be extremely coherent in terms of our values and actions. But is that true?

Parting Questions…

- How do we “reclaim” positive interpretations of commitment, responsibility, predictability, and accountability?

- Is work the primary currency of accountability and commitment?

- How do we create networks of trust, safety, and respect?

- How are our mental models of work influenced by the perception of “voluntary” employment (employees can leave, at will, and get new jobs)? Is that fair to those who cannot simply up and leave?

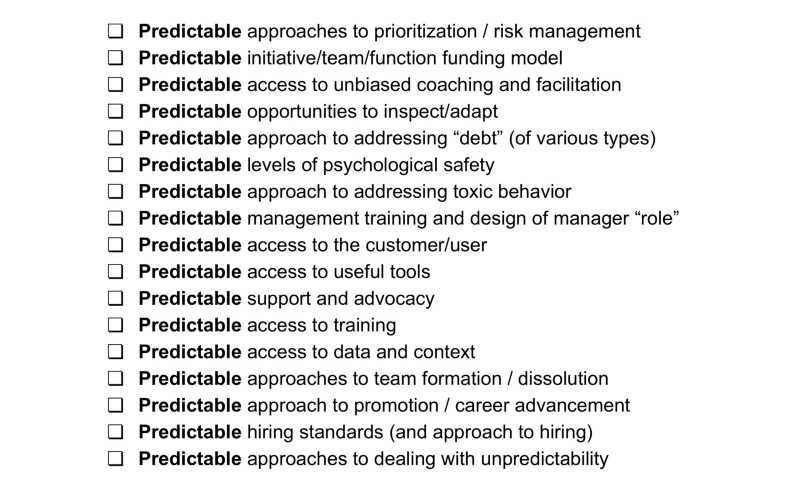

- Does coherence and predictability trump “health” ? Speaking of predictability. What if we spoke of mutual predictability? For the individual contributor, what would a “predictable” organization look like?