How do product managers lose the trust of their team?

How they communicate with their teammates plays a big role.

Scenario

A product manager says “I think we should stop iterating on this feature.”

The designer and engineers on the team disagree. They’ve been reviewing some customer feedback, and they’re not very proud of this work. In their opinion, the interface needs usability tweaks and there’s some refactoring left to do.

So they let the product manager know about their concerns.

Let’s imagine four sample responses from the product manager:

- “Nothing looks wrong about the UX to me. It is totally usable! And I don’t like when we gold-plate. This is finished based on the acceptance criteria. Time to move on.”

- “Well, we committed to finish this by the end of the month and then start on Project X. I was chatting with Marvin from Marketing, and Project X is getting a lot of attention from Linda (the CEO).”

- “I just don’t see how these usability tweaks and refactoring are the most important thing we could be working on. I mean is it more valuable than Item A? Customers and customer support have been begging us to do Item A since last year. Can we really justify that? What is the value of slightly better UX?”

- “If you feel strongly about this, then go for it. What would make me a bit more comfortable would be for us to revisit our one-pager for this mission — the one we wrote together — and make sure this additional work aligns with our goals. And then spend a couple minutes reviewing other things we have discussed doing, and see how what you are proposing stacks up. I’m fine with whatever the rest of the team decides to do, but I care about us really being thoughtful about these choices.”

Review

What does these responses convey? Let’s review them:

In #1, The product manager is telling a designer and engineer how to do their job.

In #2, the team felt coerced into that commitment. It never felt right. A “back of napkin” estimate suddenly turned into a hard commitment. And what else was discussed with Marvin from Marketing? What context are they missing? And what is Linda paying attention to? Is that happening in meetings that they’re not a part of?

In #3, the product manager is trying to make a case around value. But there are a number of things that feel off about this. She is marginalizing the team’s perspective. Customers have been begging for LOTS of things, so why Item A? She is questioning the value of UX. Pride must be worth something, too, right? Even with good intentions, this probably will not go over all that well.

In #4, the product manager shows support for her teammates. She expresses her needs—about really being deliberate about these choices—and tries to make sure the team stays grounded in their mission.

There’s a spectrum here.

Coherence (or lack thereof)

Engineers and designers are trained problem solvers (and problem definers/explorers, and systems thinkers, and cost/benefit analyzers, etc). They can sniff out incoherence a mile away, even if it isn’t their individual area of focus and expertise. So, while a designer may not be a “business expert”, they’re likely able to sense a business strategy that doesn’t add up. They can also tell when someone is flat out guessing.

When they (engineers and designers) repeatedly can’t see the impact of their work, or impact is wrapped in success theater, or the product manager’s actions are incoherent, or explanations are weak and opaque…they are likely to start losing faith and trust. Even small and innocent things can be a trigger. Consider the example from #2 where the PdM happens to have interacted with lots of people outside the team. That’s good! Interactions are good. But the mere distance, coupled with some communication gaffes, can turn a positive thing into a troublesome thing. The team feels out of the loop, and feels less in control of the outcome.

Often, product management will point to the fact that “things are going VERY WELL, we must be doing something right!” Consider:

- That doesn’t mean you couldn’t be doing better

- That doesn’t explain how the PdM’s or team’s decisions have contributed to that success (maybe current success is a result of bets placed years ago)

- It is just not a very rigorous or coherent way to make your point

This could all be best summed up in a quote from a developer:

We spend all day, every day, accountable to this tickets. Scrutinized. Under the gun. Our designs have to work. Our code has to work. QA literally tries to break what we do. People count “points”. We’re told stand up and give statuses every day. Now where is that same rigor for our product manager? When they overrule us, or challenge the value of our work or suggestions, where is that same focus on their decisions? In fact, when things go wrong, we just get blamed for being slow.

The Point

So what is my point?

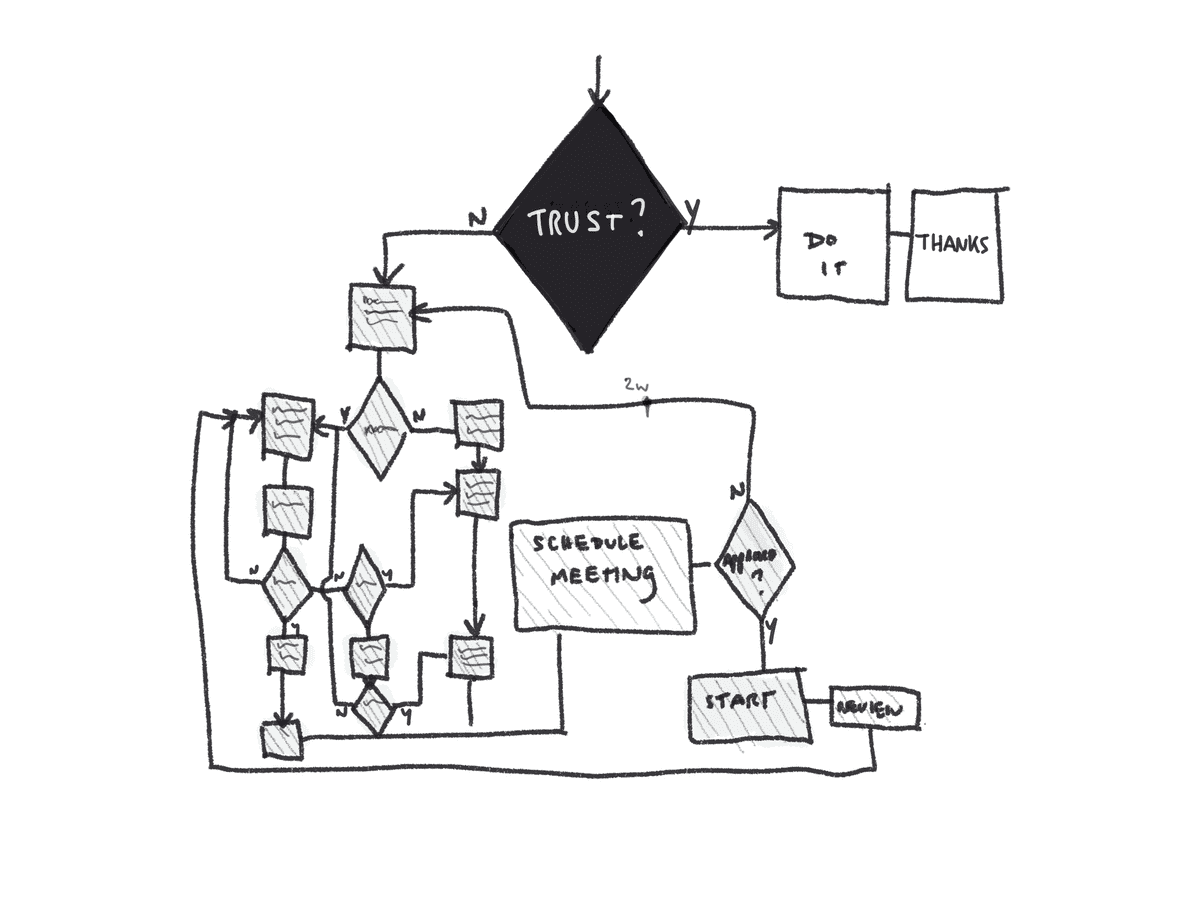

First, the obvious. Trust is so incredibly important. I truly believe we enter work relationships with a combination of trust for our teammates AND the collective weight of past conflicts AND whatever biases we have about roles & responsibilities. This is why you’ll need to work to increase and preserve trust and confront your own stereotypes of those around you.

Second, product managers need to be especially aware of how their language can be interpreted (especially when they and their teammates are stressed and/or impatient). This is why I believe designers and engineers who transition to the product manager role will have a bit of an edge: they know how things might come off. They’ve been there. For example, they know how awkward it can feel to be relayed information second hand from people within your company with obvious context missing.

Third, note how #4 is helped by using frameworks and other patterns for getting out of everyone’s head. They help.