I’ve been thinking about (and hearing about) continuous improvement a lot lately. This past weekend I had the pleasure of attending my first Agile Open event in Berkeley, CA. The experience was rewarding on multiple levels. Within a couple hours I had become part of an instant community of fellow Agile-nerds. Together we spontaneously created a 30 session 2-day unconference. And the supportive community helped me tackle topics I have been struggling with lately.

The following covers some new thoughts on continuous improvement inspired by Agile Open. New friends Rob Carstons, and Chris Young really helped me germinate a vague idea into something more solid.

As Pablo Picasso once said, “every act of creation is at first an act of destruction.” Continuous improvement exists against a backdrop of atrophy, entropy, decay, adaptation, expansion, growth, evolution, and disruption.

Consider mitosis and apoptosis. With mitosis, cells divide and growth occurs. When a tissue or organ reaches the right size, the process slows. With injury (necrosis) or periods of growth, the process accelerates. Apoptosis, on the other hand, describes healthy cell suicide. The Greek word apoptosis refers to the “dropping off” of petals and leaves from plants and trees. When a tadpole becomes a frog it loses its tail. Billions of cells die in our intestines every hour. The human hand begins as a solid blob until the cells separating our fingers undergo apoptosis. And insufficient apoptosis results in uncontrolled cell proliferation (such as with cancer).

Continuous improvement is not a simple act of addition, and neither is growth.

At least from the perspective of shareholders, growth is key in the current tech landscape. A 2007 McKinsey research report titled Grow Fast or Die Slowdescribes the advantages afforded to high-growth companies:

- They offer a 5x return to shareholders compared to medium-growth companies

- The fastest growers (>60% when they reached $100 million in revenues) were 8x more likely to reach $1 billion in revenues than those growing less than 20%

- They succeed despite margin or cost structure This ecosystem is extremely volatile and out of equilibrium, with rapid technological change, cultural shifts, and cutthroat competition for resources. Growth is the goal; it has big advantages like greater capitalization, market share, mind share, and access to resources. But like the human cells above, the entrepreneurial muscles and tissues we create and grow exact a high metabolic overhead. Information flow is reduced. We spend more to manage dependencies and integration. We must eat and digest more resources to survive.

It’s not just about growth either: all players in the ecosystem are facing eventual disruption and extinction (see Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction). Every day of growth and existence involves a potential parallel path of decay and atrophy. In this context, continuous improvement isn’t merely about keeping our skills up to snuff, or honing the rough edges of our Agile rituals and practices. It’s about survival. The dynamics of adaptation and evolution are the same, but the pace is massively accelerated.

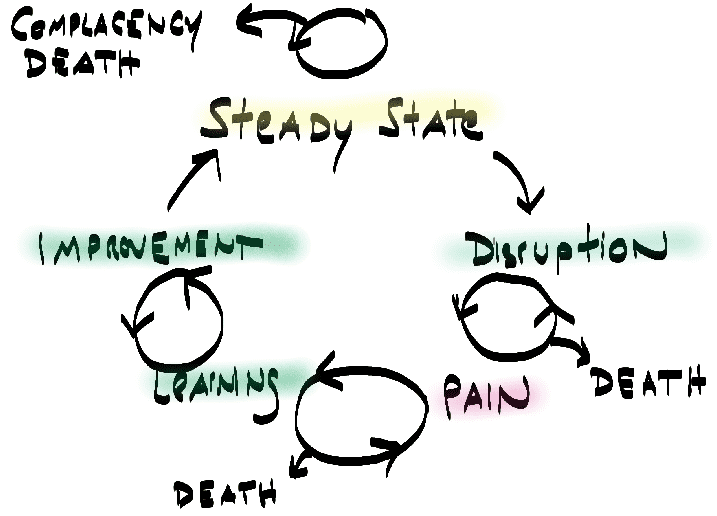

Let me present the basic model we developed and played around with at Agile Open.

How does this work? Let’s start out with the basics:

In Steady State we are not improving, but we may be using newly improved capacities

With Disruption we experience a change in the equilibrium. We experience a stressor from an internal or external source

The first response is Pain

Pain reveals information. And we Learn

Learning leads to potential Improvements

We reach a local optima and move to a Steady State We have four primary loops with three not-so-ideal end states:

Disruption and Pain predominate when we first encounter the stressor. If the stressor is large, then it leads to Death. The disruption and pain was too great

If we are in Pain, we may continue to Learn. But if we can’t translate that into Improvements then we will eventually reach Death. We are stuck in a downward spiral not being able to apply our learning.

When we combine Learning with Improvement we have a virtuous cycle that lets us translate disruption driven information into improvements. Eventually we’ll reach a local optima

Finally, in the Steady State loop we can simply “ride it out” for some period of time. Without further disruption we risk descending into a cycle of complacency, and finally Death. This cycle is experienced on the individual, team, product, organization, industry, cultural, and multi-cultural level. Some examples:

Individual. We first exist in the womb, a decently safe steady-state. Birth is a form of painful disruption. We learn and adapt. Hit plateaus. And continue through the cycle. If we suffer a grave injury then we are disrupted and stuck in the pain cycle, and may die. If we get stuck in a steady-state, then we struggle with a form of atrophy and death. We work to improve our work environment until a certain point where things plateau. And if things stay there we get restless and then disrupt ourselves and find a new job.

Organization. After a period of smooth sailing our industry is disrupted due to an important cultural shift. If the disruption is too harsh, we die. If we live, we learn and adapt, and improve.

Teams. Team formation is a form of disruption. Hopefully we push through to a period of learning. We get diminishing returns from our improvement efforts. Cruise a bit. And then disrupt ourselves.

Products. Products are initially disruptive. We go through a period of optimization (learn / improve), and then move to maintenance mode. It is at this point that we either disrupt ourselves with a new offering, or let the competition do that for us.

In a single culture (and organization) you can have multiple parties moving at different speeds through this loop. Consider the example of the tenured engineer who starts getting bored due to fewer challenges, more rules, and less flexibility. They have achieved steady state. While the company is happy with the steady state, they are unaware that it is leading to complacency. Our engineer starts to get an itchy trigger finger. Either they will disrupt themselves and leave the company, or the company will respond.

Or the organization with leadership that can see the impending threat but has trouble inspiring a sense of urgency. Or the sector within the larger global landscape that is on the forefront of disrupting the incumbents.

With this model in mind, we can take a broader view of continuous improvement. Let us discuss the key levers an Agile Coach could use to impact flow through this cycle:

- Assess the states of individuals, teams, the organization, industry, and broader culture (if working internationally). Where are they in the cycle? Do they realize where they are?

- Preserve the safety of Steady State when it is helpful and when it help consolidate gains

- Move people out of steady state to Disruption at the right time

- Sense Pain quickly, soften pain of disruption, and shift quickly to Learning

- Facilitate the Learn/Improvement cycle

- Realize when a local optima has been reached for local improvement and push ahead So let’s get back to continuous improvement. Gary Hamel refers to flexibility as “planned adaptation” for the “expected” and agility as “unplanned adaptation” to the “unexpected”. Flexibility, therefore, requires the ability to see the future which is rather difficult. Agility assumes an unknown future.

In the Quest for Resilience Hamel writes:

Strategic resilience is about having the capacity to change before the case for change becomes desperately obvious. An accelerating pace of change demands an accelerating pace of strategic evolution, which can be achieved only if a company cares as much about resilience as it does about optimizationHe continues:

The goal is a company where revolutionary change happens in lightning-quick, evolutionary steps — with no calamitous surprises, no convulsive reorganizations, no colossal write-offs, and no indiscriminate, across-the-board layoffs. In a truly resilient organization, there is plenty of excitement, but there is no trauma.Hamel’s version of resilience is similar to Nassim Taleb’s “antifragility”. Antifragile systems are not merely robust — able to withstand threats — but actually thrive in volatile environments.

With all this in mind, I want to propose a broader vision for continuous improvement that extends beyond surfacing and fixing sprint impediments and eeking the final 10% of craft competence out of a team. It’s the part of the puzzle that many companies miss when they buy into an Agile transformation only to be stymied with the next seismic shift in their industry.

Continuous improvement is the response to the drumbeat of atrophy and carrying dead weight. And it works hand in hand with continuous disruption. Basic process improvement and optimization relies on a repeatable future. Continuous improvement addresses a deeper need.

The goal of continuous improvement is to, at a minimum, grow today while remaining as Agile as you were yesterday. And even better: to increase that Agility during growth. This is not optimization. This is resilience.

In a sense that is what Agile Open was to me personally. A bit of disruption (a friend recommended that I attend and take the plunge), some initial pain understanding the format and getting comfortable, learning, improvement, reflection in the form of this post, and now I’m off to the steady-state (bed). Cheers!