Here’s an observation after interacting closely with a number of product teams.

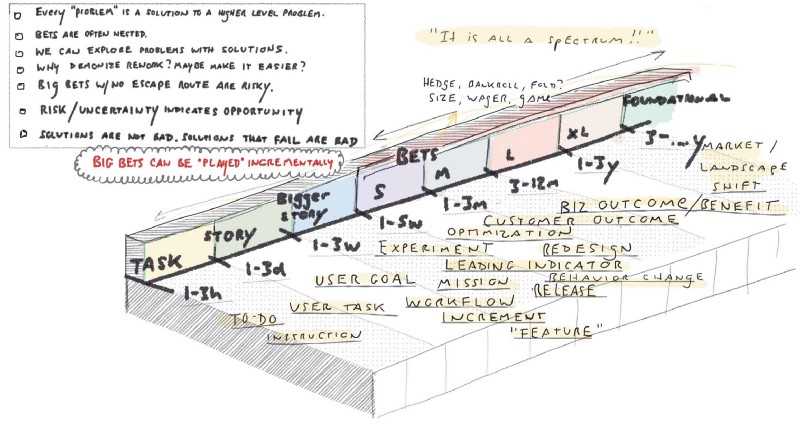

There’s a gap in the “messy middle”. Where is the messy middle? Let’s imagine a spectrum of work decomposition:

Of course this is “nested”, meaning that 1–3 hour “stuff” drives 1–3 day “stuff”…all the way to the huge bets that define why the company even exists.

In my experience, there is a gap somewhere in either the 1–3 month or 1–3 quarter range (depending on domain/context and current throughput). Below that gap, the work is known. It almost needs to be. Without some level of clarity, the nuts-and-blots day-to-day would devolve into chaos. Above the gap, there’s strong pressure to “paint the picture” and “simplify”. But in the messy middle things go a little sideways.

It’s that fine line between (too) general and (too) specific.

Why is this a problem? It is precisely this range — somewhere between 1 month and a couple quarters — where we have an opportunity to connect output to outcomes. Stuff too the left will be by nature more prescriptive. Do this. Do that. Make this possible. Enable the user to do this. Stuff to the right will be “too high level”…good for board decks, but short on details. Addressed with care, this middle range can be a great place to advocate for outcomes and connect that shorter time-frame work to outcomes. Overlooked, and you just slip further into the feature factory…with bigger batches.

Why does this happen?

- This range is typically a handoff/transfer point in org hierarchies (e.g. person X owns one side of the gap, and person Y owns the other side of the gap).

- Stuff doesn’t change frequently enough to force a regular restatement of reality, which means that there’s no immediate motivation to keep this range up to date. Put a little differently, “stuff” on the ground changes a good deal, but it isn’t really worth changing how that manifests in this “middling” goal range.

- The “low level” stuff spanning a couple weeks is “too technical”. So there’s a temptation to define the middle-ing stuff as consumable output-focused junks (“oh yeah, we’re building X”). The solution to this, I think, is to maintain a coherent view. At all times you should have 7 levels represented and up to date (or at least 6 levels, if decade goals are too ambitious). This takes work because as mentioned we tend to have to dream up these middle-ing goals prematurely in a vacuum, and then the “real day to day work” happens at the shorter time-frame levels.

Be able to “walk the tree” from every 1–3 hour item THROUGH all the steps up into a 1–3 year item (at least) to avoid the “messy middle”. Once you’re able to do that, try to advocate for making these messy middle goals more outcome focused.