Saving the persona from itself, from selfish UX, and other tips

An engineer once described a persona exercise as “theater camp”. I thought about that for a while and realized what she was getting at. Here I was coming from the UX world, running the team through a song and dance exercise with imaginary people, stickies, and line drawings. The “creative” (me)

An engineer once described a persona exercise as “theater camp”. I thought about that for a while and realized what she was getting at. Here I was coming from the UX world, running the team through a song and dance exercise with imaginary people, stickies, and line drawings. The “creative” (me)

felt comfortable — I was in my element — but to the attendees it was like a nightmarish new-age UX drum circle.

It’s like a wrestler doing their first yoga class. Or me doing pair programming or trying TDD. I tell the one about role playing games being the inspiration for personas. Crickets. My jokes fall flat.

Role Playing Game Character Sheet aka Persona

Role Playing Game Character Sheet aka Persona

One solution is to retrench and to consider personas as the UX rallying call. People are going to play along whether they like to or not, embrace my powerful UX Empathy! But I think that is shortsighted. I’ve experimented, and have found some things that work.

Yes. They’re Fake

Personas have a shaky reputation among software engineers. And that’s being generous. I’ve been in numerous situations where teams openly (and forcefully) expressed their distrust, dislike and aversion to personas. Mini revolts ensued and hand drawn posters faded and magically disappeared. One engineer described personas as the “Joe The Plumber”-ification of software development. Ouch.

In the words of engineers they seem “fake”, “contrived”, “artificial”, and “forced”. It would be easy to write this off as a lack of empathy or imagination (which ironically is reverse lack of empathy), but in my experience the opposite is true. Teams genuinely want to connect with users. The reality is that personas, at least initially, are all of those things — fake, forced, and contrived — while at the same time being extremely valuable.

The reality is that personas, at least initially, are all of those things — fake, forced, and contrived — while at the same time being extremely valuable.Pick a character from a favorite book. You’re pulled in by the story. At page one-hundred of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men we know Lennie and George well enough to predict impending doom when they meet Curly (and Curly’s Wife). The characters are “real” because we suspend reality long enough to embrace the fiction. Ethnographers and UX researchers do the same: suspending surface stereotypes long enough to embrace a more complex reality after spending weeks/months in the field.

Both take a leap of faith — to start with something wishy washy and “fake”, stay curious, and keep digging for something more poignant and actionable. We create a generalization as a starting point for learning. Personas are helpful. Use them correctly and you will develop better products. Force them on teams — “inflict” them on teams, to quote an engineer — and you’ll erode trust, detach the team from the user/customer, and harm the end-product.

Whip-Cracking Personas

The worst abuse of personas is when they’re used to basically tell people what to build and who to build it for. They embody the why, who, what, and how without any room for exploration and disagreement. Any person in their right mind will start ignoring these and thumb their nose. In a retrospective an engineer once exclaimed:

You want me to spend the next three months of my life working on something for an imaginary person you dreamed up for the kick-off deck?The rest of this post will assume that you’re intellectually honest and rigorous, and that you are open to engaging with your team to build a better product. If that’s not the case, then you’ll probably get bored.

Yes I’m Guessing

A great start is to eat the humble pie and openly acknowledge that you’re guessing. This seems trivial, but it might not be immediately clear to the team that you are consciously and intentionally “making believe”. These “proto persona” (a first pass persona not based on validated assumptions) represents your best guess at the moment. The challenge of product development is to iteratively validate these “who” assumptions. Who is this fictional character? What job do they do? When we’re one-hundred pages into this book, what will we know?

How do you structure and visualize this approach? Instead of a static (and quickly stale) persona, we’d use a Kanban board (or “canvas”) to prioritize assumptions, and then plan and execute experiments.

The challenge here is that openly acknowledging how little we know is not exactly the stuff of CTO and VP of Product dreams. It makes people uneasy. Validated experiments don’t result in deployed 1s and 0s. Teams are frequently measured in terms of output, not outcomes. But if you foster a culture that is failure-safe and focused on learning you’ll be surprised by the engagement this inspires on the team.

If you’re going to make the persona (and your assumptions) visual, commit to keep iterating on the content as the team learns. A stale persona is worse than no persona at all.

“Real” People

Another approach — and one I’ve found very effective regardless of organization culture — is to focus on “real” people instead of generalizations. This is the persona gateway drug for the uninitiated. Knowing that this human actually exists in flesh and blood does wonders.

At first I was skeptical and braced for the valid “low N” argument (focusing on one person is the queen of small samples). In a fit of “ok, I’ll try personas one last time” I took pictures, video, and audio. I had the team design their own persona template based on a collection of real humans. Together we referred to the users by their actual names.

These “personas” — while not strict personas — came alive. Because they were actually alive. The team could jump on the phone and chat with them. What was impressive in this case was that the team had a much easier time moving from the specific to the general. They noticed commonalities. We developed generalized personas by going backwards — which essentially mimics how skilled designers and marketers create personas in the first place. It was a good example of experiencing the thinking process instead of mandating it.

Starting with Fake Fake People rarely gets you to Real Fake People### Salience

People can be extremely lazy with the types of media they use for personas. And designers are often the main culprit. They’ll create complex and beautiful persona templates while missing out on opportunities to use video, audio, and work product samples (e.g. spreadsheets, forms, plans, etc.) The templates are so rigid that any new learnings are impossible to incorporate. In short, they’re made for Show, and not Tell. Cute for portfolios, but not so helpful for teams.

In short, they’re made for Show, and not Tell. Cute for portfolios, but not so helpful for teams.Let’s say you’ve interviewed ten people and you’re starting to find some commonality around the technology usage dimension. Consider editing down clips of video (or audio) for that dimension and splicing it back to back. This will drive home the point with more salience and impact. Most importantly you’re letting the team explore the connections instead of force-feeding your biased summary of findings. Work backwards from the specific to the general, not the other way around.

The granddaddy of persona fastracks is the “real world” customer visit. Rent a van and go. I’m amazed by how few product managers, let alone engineers, actually engage with their customers and users in their offices. Your precious UX breaks down with eleven open browser tabs, interruptions every three minutes, and a barking boss down the hall. No slick persona can replace this experience … especially second hand through a UX researcher or product manager proxy. Taking a full day off away from the screen might seem like a productivity killer. But so is building things people will never use.

In a pinch video can work too if your org is pushing back, or if visiting customers on site is impractical. At a former gig I filmed “confessional” style videos with twenty odd customers/users. I set the context and lowered the customer’s guard. No topics were off limits. The end result was “loved” by even the staunchest persona haters. It felt “real”. The same held true for monthly customer research panels where we invited customers to speak to a room of 15–30 engineers over lunch. Even the staunchest persona-loathers enjoyed these sessions (and the free lunch didn’t hurt).

Salience Part II: The Story

What excites people more: 1) knowing how old a person is and that they like puppies, or 2) knowing that a person saved a stray puppy from freezing water on the eve of their 30th birthday during a freak ice-storm in Wisconsin?

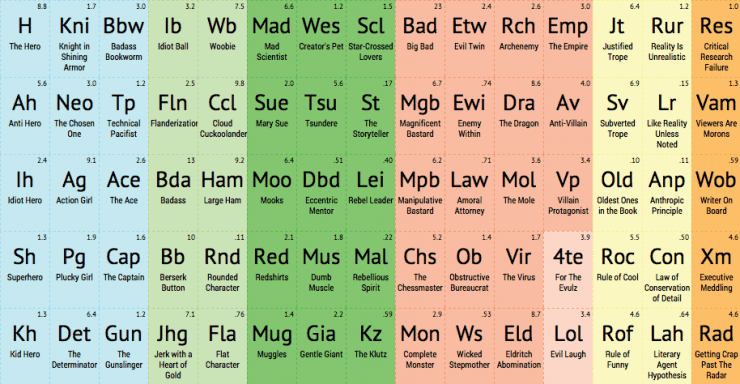

Check out the period table of storytelling and get lost for an afternoon.

Periodic Table of Storytelling

Periodic Table of Storytelling

The summary and bullet-pointed nature of personas is the persona achilles heel. I remember interviewing a person who was caught in a terribly difficult financial situation. He was terrified that he would let his elderly mother down by mismanaging the property she had entrusted him to rent. Her care at the assisted living facility depended on it. Now that’s real. No bullet point can capture that. Playing the audio to the team captured it perfectly without any platitudes about empathy.

This is why personas should be used in conjunction with customer journey maps and other time-based visualizations and artifacts. Don’t feel limited by the format or template of the personas. Consider storyboards, picture montages, video montages, and more traditional journey maps.

Some of the caveats above still remain true. A “proto” customer journey map is still a hypothesis. Making it more visual doesn’t solve that problem. But by “working backwards” from qualitative research you can make this exercises pack a bigger punch.

Jobs To Be Done

Jobs-to-be-done is an interesting counterpoint to traditional personas and something I’ve seen resonate with product development teams. I’m not sure I’m a fan of doing away completely with personas, but I do think jobs-to-be-done makes a great case for focusing less on the classic product marketing wheelhouse of demographics and stateless, causality-lacking generalizations.

These attributes, generally in the form of demographics, do not bring a team closer to understanding a customer’s consumption, or non-consumption, of a product. The characteristics of a Persona (someone’s age, sex, race, and weekend habits) does not explain why they ate that Snickers bar; having 30 seconds to buy and eat something which will stave off hunger for 30 minutes does explain why. (Intercom)With B2B you frequently encounter situations where you’ll have customer wear different hats depending on the size of the company. Users are grouped by needs and goals (both emotional and job-related). Imagine two CEOs, both with similar demographics. The president of a small company might wear “all of the hats”, while the CEO of a large company focuses on top-level decisions. The SMB president embodies many jobs-to-be-done, least of which is trying to manage the wrenching stress of overseeing a small business.

There is a subtle difference between

“This person is stressed. This person is overworked.”and

“This person is hiring our product to reduce stress in their day and to work more efficiently.”A big word of caution is to put too much emphasis on official roles prescribed in your product. What is an Administrator exactly? Are they all the same? Do all Read Only visitors have the same needs? Don’t create personas directly from your system-roles.

Relationships Matter: No Persona Is An Island

A major failing of traditional personas is that they fail to describe relationships. Relationships drive collaboration and interactions. Relationships create product challenges that extend beyond the singular wants, needs, and egos of individual people. And for the purpose of engaging teams understanding relationships drives empathy and novel solutions.

Let’s say you have a golfer and a caddie. What are the inputs and outputs of that relationship? The golfer is relying on the caddie for local knowledge and emotional support when she shanks the ball into another fairway. The caddie is relying on the golfer for money, for conversation (perhaps), and for regular work. Both have a relationship with the Pro and other Golfers.

The relationship view is a much needed layer of understanding. The real opportunities for products often exists along the edges … not at the nodes. Work passes between people, not inside the confines of single personas. A successful product addresses the needs of all parties. These diagrams don’t fit into the neat and tidy persona templates, but they express a more realistic set of assumptions.

The Why

Observing humans is one of the great catalysts for invention and innovation. It’s how you develop products that magically read the customer’s mind even if they’ve asked for something entirely different. You notice the subtleties. Your design decision batting average improves.

But as they stand personas have a bad rap. Framing personas merely on their capacity to drive empathy is too short sighted. And frankly it also feels elitist. It casts engineers as lacking empathy for users, when in fact they rightfully lack an appetite for shoddy assumptions.

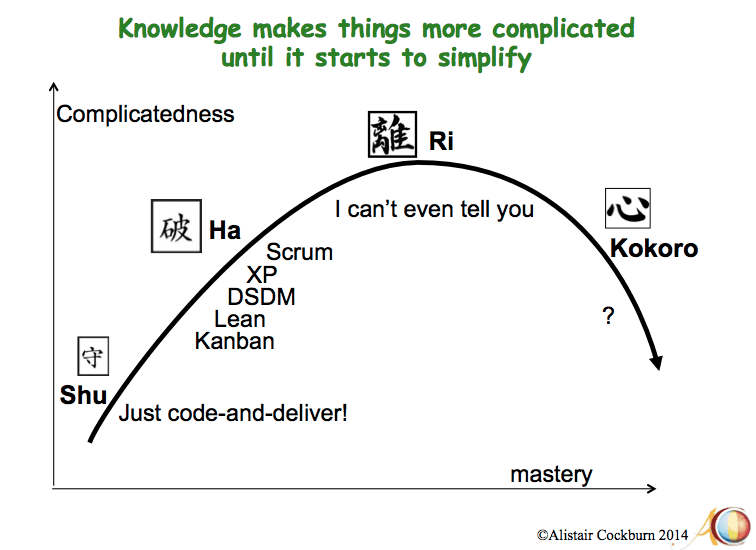

There’s a couple reasons why “experienced” cross-functional teams perform better. The first is that they know when to trust and challenge their intuition. The second is that they know how to ask better questions and that staying curious is the key to the game. Third is that they combine techniques and have mastered the core skills (“just code and deliver” below). Personas, and their inherent ambiguity, definitely makes things more complicated at first …

Shu Ha Ri Kokoro — Allistair Cockburn

Shu Ha Ri Kokoro — Allistair Cockburn

When working with an inexperienced team this can be a challenge for the UXer. You know that the persona process can yield better, leaner, more simple, and more effective product … but honestly it all feels a little hokey. Hopefully the advice above helps, and I’d love to connect to learn what has worked for you!

Don’t do personas for the heck of it. Build better products together.