Note: I transcribed this post from a coaching/training session. Hopefully the conversational style works OK, and it isn’t too choppy. Also, I am very sleep deprived due to the new baby! Which means I’m terrible at proofreading. But in the spirit of continuous delivery … :)

Today we are going to talk about how to advocate for, prioritize, and put a dollar figure on non-feature work (e.g. refactoring, tooling, and infrastructure projects). The discussion is the same for hiring for understaffed roles, and really, for continuous improvement in general.

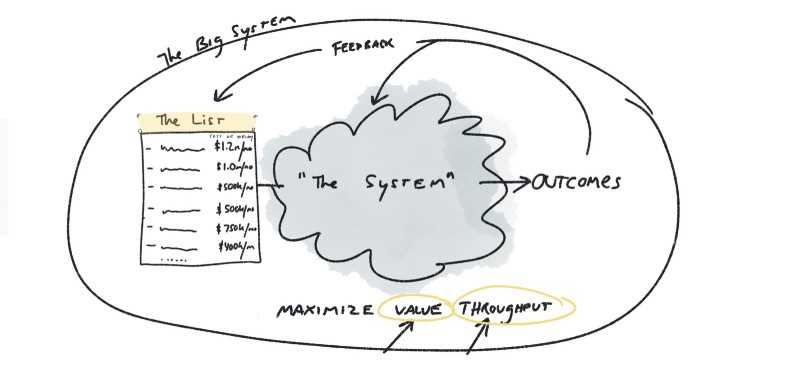

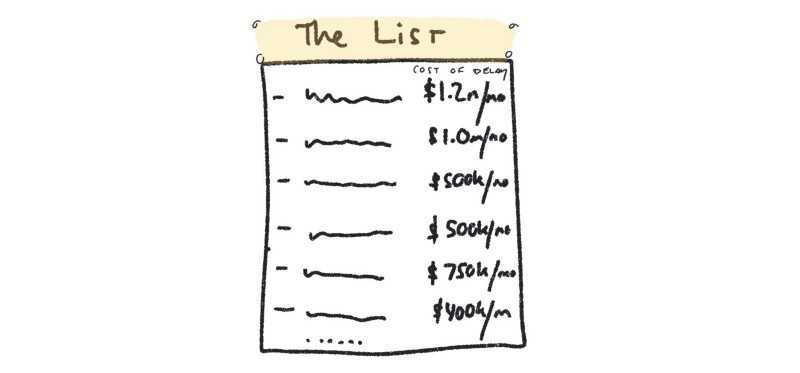

So, your organization has a list of valuable, so called “customer facing” or “business facing” things to work on. And you’re trying to advocate for getting your important “non-customer facing” thing on that list (in some environments I have heard this referred to as “non-value add work”…something I really dislike).

Let’s state value for the items in this list (the customer facing stuff) using Cost of Delay … dollars per some period. This is the cost — per time period — of not pursuing this option. In this case we’ll use months.

Note: We might change the order of these items based on expected duration (using WSJF — weighted shortest job first)

Note: We might change the order of these items based on expected duration (using WSJF — weighted shortest job first)

.Like most companies, you’ve got lots of potential opportunities in this list. Some reduce costs or prevent costs from increasing. Some add revenue, or protect revenue. And some do interesting things like purchase information and buy options.

But let’s keep it simple for now.

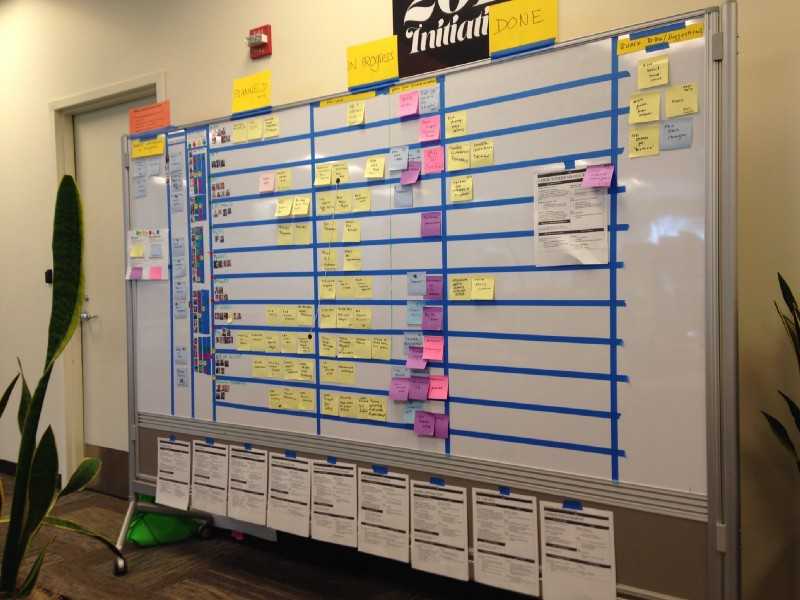

We have our list. Now, we have to design a system to maximize value throughput given all that valuable work. But let’s just assume that system exists — today — in your organization.

At the risk of dangerous oversimplification, this system maximizes value throughput which has two components … extracting as much value as possible from opportunities and the throughput … the rate at which these items move through the system. Of course there is a feedback loop…I’ll draw it because its important.

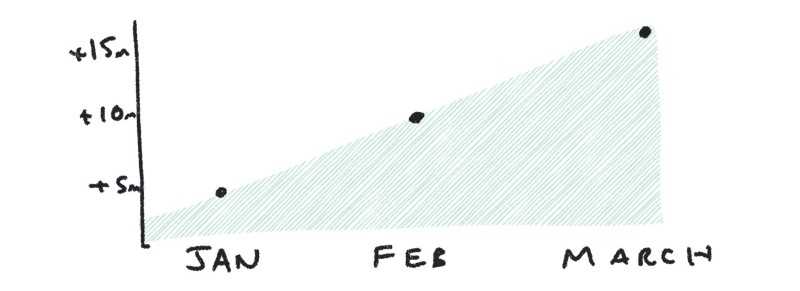

So… we have a system for value creation. And that system creates value at a certain rate. In our example, let’s say it is adding ~ $5m in monthly value …every month. So in three months, we’re generating $15m more monthly because of our work

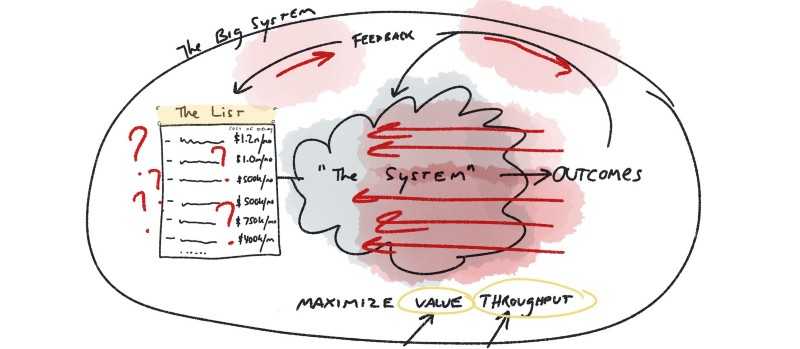

Now, let’s say something slows down that value creation.

It isn’t flowing as quickly as we need it to flow. Maybe … the feedback loop gets noisier. Or we misjudge some opportunities. Or we’ve onboarded lots of people, and it is hard to get them up to speed. Or some role — QA or Ops for example — gets overloaded. Or quality issues are injecting a lot of unplanned work into the system. Or maybe morale is dropping and valuable team members are leaving. It could be lots of things.

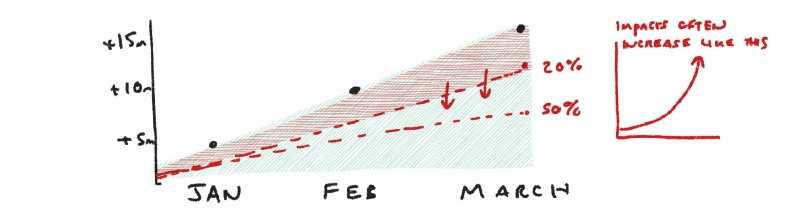

This slows the throughput of value. If it slows the system by 20% … well, that is $1m less value creation per month.

And if it is getting worse non-linearly, like many of these things do … it could be 50% soon. Or 75% slower if not addressed. Easily one of the most important things to work on! Orgs address this immediately, right? I’ve seen the 50%+ example … and the answer is… not always. That’s polite. Very rarely. Which is kind of insane.

Anyone who has advocated for refactoring, tooling, continuous improvement, hiring QA, hiring Ops, knows the challenge here.

The cause and effect is often not immediately visible. First, and this is a no brainer, it simply isn’t visualized. Instead of visualizing flow, the org focuses on resource allocation, estimates, bulky annual plans, project status reports, the neat and “official” org chart (not the real org chart), and push-based goals and commitments. These sense-making tools don’t focus on the flow of value at all. And the Cost of Delay of the system, its queues, steps, etc. is unknown. This is a big problem.

It’s a problem because it leads to the wrong conclusions and responses. For example, when things start to slow, these are some common responses:

- We need hire more people!

- Increase work in progress! (which makes the problem worse)

- The emergence of unofficial fast track lanes…and official fast track lanes

- Teams cut corners to hit their estimates (makes matters worse)

- Teams work around a starved QA and Ops teams… giving the impression of throughput, and further exacerbating the problem

- More local management is hired, because our tendency to think it is a management/accountability/process issue

- Traditional program management / portfolio / project management … which can make issues even more opaque by focusing not he work, not the system around the work

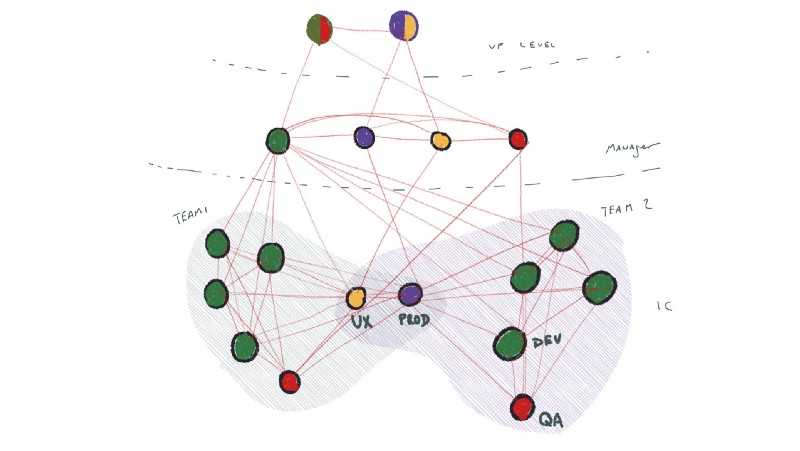

- Blaming individuals instead of focusing on the system. People are getting lazy! They’ve checked out! Most approaches don’t account for the space BETWEEN individuals and BETWEEN the work. Work these days more resembles value creation networks than assembly lines…the edges being information/knowledge transfer. You can see above that our instincts often make the problem worse AND more opaque.

Visualizing flow — and adding light constraints (WIP limits) — helps us make sense of what is actually going on.

Even when we do visualize flow, we often bump up against an inconvenient truth and retract. The reality is that most org charts are not designed to deal with these cross-functional and systemic challenges. They’re great at setting high level goals from the top. And great at the local functioning of teams. But anything in the middle is murky.

Examples of inconvenient truths I have observed in my career

- You really do need embedded QA on every team

- You need to make a major investment in supporting a DevOps culture

- Or the product team isn’t doing a great job of prioritization

- Or the product’s complexity requires a ton of maintenance and refactoring

- Or the head of marketing shouldn’t be micromanaging roll-outs

- Or that the business model simply isn’t working None of this can be handled in a vacuum. There’s probably no one person directly accountable, or that can decide this unilaterally… until that someone with a C in their title, and even then … it might need the CEO to settle the tie. Just look your average “product development” org…

But backing up to the original topic.

The key value in continuous improvement is addressing the value and value throughput parts of the equation. There is very real value in things like refactoring, restructuring, tooling, better customer research, more instrumentation, debt workdown, inviting customers into the design process, etc. It literally could be the MOST IMPORTANT thing you might be able to work on. This is why arbitrary % allocations or side-projects, or. “1 item per sprint” guidelines sort of miss the mark.

To truly advocate … you need to have a sense of:

- A definition of value in your context.

- The amount of value passing through the system

- How certain things impact that… making sense of the system Value needs to be framed in terms of time. And it needs an apples to apples measure … dollars proves to be a lot better than a hand wavy spreadsheet. I suggest learning more about Cost of Delay. It is a great catalyst for conversations about your business model, and how real $s are created.

And then sensing. Visualizing is one tool. WIP limits another. Great retrospectives — on the team level and across the org — are another. Transparency is key, and transparency requires psychological safety and a deep desire to work across boundaries and silos. You’d can’t fix/talk about things you cannot sense. Speaking of sensing…

Once you have this things … then it is about making a straightforward business case. Example:

Right now [some issue] is reducing our value throughput by X across the board. If we don’t do anything about it, that % will increase.Which brings up the final — and perhaps greatest challenge. Most orgs are not optimized for mid/long term outcomes and sustainability. They are optimized for growth and short term outcomes. Which means they perhaps bias their sense of value by its impact on the short-term top line (or perception of their investors, VC firm). It’s like getting a spray tan to impress a date, or going on a crash diet. That said…maybe that will keep you in the game.

I can’t solve that for you … but I do know that by sensing the system, creating safety, and really having a deep conversation about value … that you can open up the discussion to the value of “non-feature” or “non-functional” or “non-value-add” work.

In short, figure out the impact on value throughput which means figuring out what is valuable. Good luck!