Why most estimation, ROI calculations, and heavy upfront planning is a waste of time in SaaS

This post is about fear and uncertainty, how we respond to that uncertainty, and how we accidentally perpetuate learned helplessness in software development.

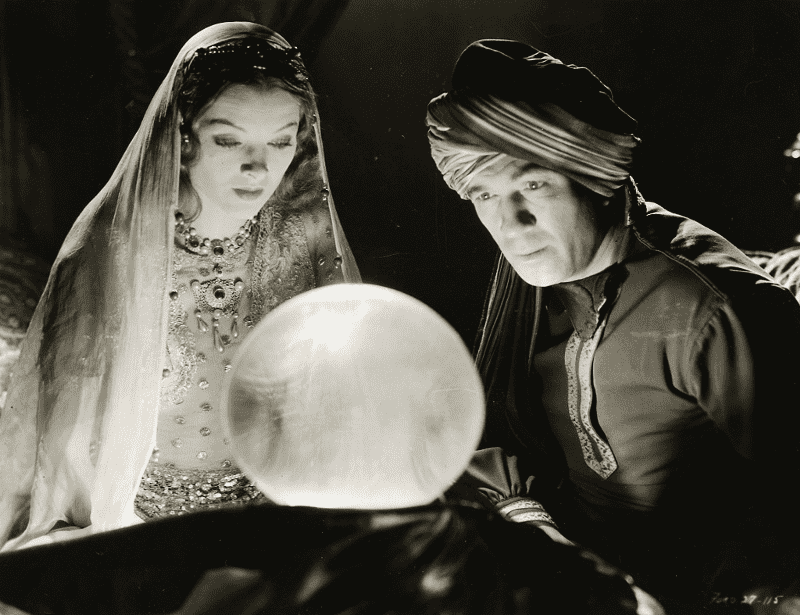

http://lisapapineau.blogspot.com/2012/03/actresses-and-crystal-ball.htmlSaaS products are service touch-points. Customers don’t buy, they rent or pay-per-use. Adding features to the product cannot be equated to adding features to a physical product. The feature may be “shipped”, but more accurately you are establishing a potential value stream in a complex service ecosystem. To quote Dave Snowden

http://lisapapineau.blogspot.com/2012/03/actresses-and-crystal-ball.htmlSaaS products are service touch-points. Customers don’t buy, they rent or pay-per-use. Adding features to the product cannot be equated to adding features to a physical product. The feature may be “shipped”, but more accurately you are establishing a potential value stream in a complex service ecosystem. To quote Dave Snowden

, “software development needs to be seen as a service and as an ecology not as a manufacturing process.” Yet, the vestiges of manufacturing remain.

Complexity triggers our defense instincts.

We plan. We play planning poker. We estimate. We play “buy a feature” with our stakeholders. We try to calculate ROI (the cost and reward side). We draw linear process flows as circles and call them loops. We stoke the feature factory, crank the velocity, add bullet points to feature lists, and bask in a false sense of rigor. Output soothes the nerves, albeit temporarily.

As Snowden remarks, “going through a linear process in shorter cycles or drawing it as a circle does not make it non-linear”. Our challenge is nonlinear. Therefore, you’re battling a mismatch between the problem space and the approach. Manufactured Product = linear. Service = nonlinear, complex adaptive system.

Remarked a developer friend:

After all the ****ing song and dance with estimates, it is three months later and no one is using the damn thing. It was shipped and forgotten … on to the next feature right away. We were 1.2x of estimate, yet the ROI discussed is tracking at .2 … probably negative if you figure in the technical debt we were forced to add. We’ll lose money! But hey … we are “predictable”The reality is that we are not great at predicting/understanding:

- how customers will actually use what what we build in their real-world environments

- when and what we will learn, and what opportunities may emerge

- the emergence of new technologies, changes in competitive landscape, changing usage habits, micro and macro economic trends, evolving customer needs, emergence of new opportunities

- how an individual feature will contribute to the overall value of a product from the customer, user, and/or business perspective. Customers are notoriously bad at estimating the value of a proposed enhancement

- breadth of usage and growth in breadth of usage over time

- the rate with which perceived value will degrade. Today’s delighter is tomorrow’s table stakes feature (see Kano Model)

- the actual ongoing cost of adding new functionality (maintenance, support, increase in technical debt, training, complexity, etc.) Upfront engineering costs typically represent a small % of overall cost

- the impact of various nonlinear effects caused by increased complexity (for example, doubling team size doesn’t produce 2x outcomes) But, but, but, but …. we should still try, right?

It’s not worth it. Heavy business cases, ROI calculations, project estimates, feature estimates, complex prioritization schemes, etc. — all of that upfront stuff — is mostly useless. They reinforce a linear delivery model mindset and being able to predict the items above. We might progressively narrow in on an ROI estimate over time, but solving that puzzle upfront is nearly impossible.

Your best bet is to aim resources at a seemingly valuable problem to solve (or customer’s job-to-be-done), attempt to continuously deliver value, and hone your ability to “sense and respond” based on what happens. We may not be great at the points above, but we’re better when we actually observe a response (sense) and respond accordingly. Amplify and diminish/mute/kill accordingly.

But you need to be able to move quickly, deliver value continuously, learn and experiment, and fail safely. “Our team can’t do that!” you say. That’s a problem. When your ability to move and learn quickly is compromised, we are forced to maniacally protect our resources. We MUST become clairvoyants. We MUST try to do the impossible and look into our crystal balls and correctly predict the future of a complex adaptive system (hard/impossible). You can only do that when your horizon is very short, and you are moving quickly.

We then have a self-fulfilling prophecy … because we’re weak, we impose a way of working that discourages ever becoming good at our weakness! The feature Tetris / factory starts up, and your team never learns how to iterate and progressively add value to a value stream. Worst of all, teams become overly reliant on receiving a prescriptive idea/solution vs. aggressively tackling a problem to solve, failing, and learning.

And that’s where I’ll stop for the day. Are your planning and estimation efforts actually adding value? Do they “work” (outside of assuaging internal fears, and aligning everyone’s cognitive biases)? Are they really necessary? If you’re firing on all cylinders and doing all that stuff, well awesome! If not, is this a chicken and egg problem?

Subscribe to The UX Blog

The freshest user experience content on the web. Period.