Why Read

Stop debating whether you are doing product roadmaps “right”, or whether roadmaps are evil. Look instead at the job you are hiring your roadmap to achieve. And then ask if the roadmap is the best tool for the job.

TOC

- 14 common product roadmap problems

- A summary of almost all methodology debates on Twitter

- Roadmap Needs and Being Awesome New to Product Management? What is a product roadmap? For a standard definition see here.

A Litany Of Roadmap Ills

Roadmaps are frequently abused. To save you thirty minutes, I’ve organized these observed problems into the list below.

Some of these problems are inherent to the process — you need to actively work to prevent them from happening. Others are caused by user error or deep organizational dysfunction. And some are governed by even broader effects like the planning fallacy, confirmation bias, and groupthink.

Roadmaps encourage people to…

- Horse trade initiatives, placate stakeholders vs. focusing on value creation

- Stick to the plan when the plan is no longer optimal

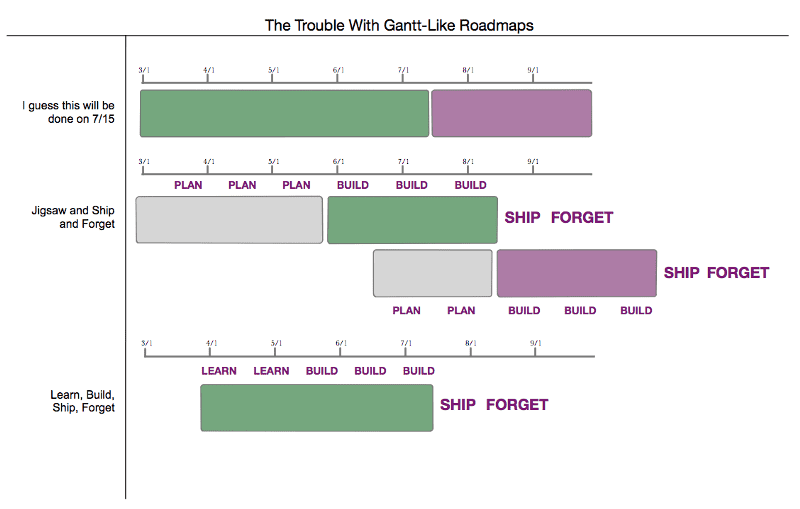

- Chase harmfully high utilization rates (the jigsaw illusion)

- Future sell, instead of relying on the current merits of product

- Prioritize new feature development (items which can be easily understood and sold) over equally promising enhancements to the existing product

- Converage prematurely on solutions

- Rely on estimates, despite the fallibility of those estimates

“Big Batch” PlanningRoadmaps …

- Encourage the illusion that efforts are linked to a timeline(when most aren’t)

- Obscure underlying assumptions, rationale, and vision. Even when described (e.g. a theme), it is still difficult to parse why the theme matters

- Institutionalize “big batch” yearly planning, which in turn decreases agility

- Encourage group think — satisficing — over focus. Initiatives lose their bite

- Fail to address the needs of all “users” (e.g. your roadmap is fine for communicating with executives, but fails to meet the needs of your front-line teams)

- Discourage experimentation and acting on new insights / data

- Create dependencies across the organization (decreases agility This Tweet from Jeff Patton wraps it all up:

Some common pitfalls I described in a recent talk:

Challengers vs. Defenders

OK. That’s a pretty hairy list. I’m not the first to challenge roadmaps. Luckily this stuff is out there in the google-verse by the boatload. You will also find debates that look something like this:

Challenger

[Methodology] is flawed

Defender

You’re just not doing it right. The real value is in [Some Positive Aspect]. Yes, some people abuse these things. Just not me …

You need to get back to the basics …

You need to stop doing it the old way …

Challenger

Challenger

What could you do such that [Some positive aspect] would be possible without the abuse, and observable negative effects?

Defender

This is heresy. Here in the real world we need [Methodology] because [Some Reason]. And plenty of great teams — you know [Company] — use them also. So you’re on crack!

Challenger

What is to say that [Company] isn’t successful in spite of [Methodology] ?

Defender

Damn you. I’m blocking you on Twitter.

Check out this overview of one of the classic Twitter debates (from a somewhat similar question … #noestimates)

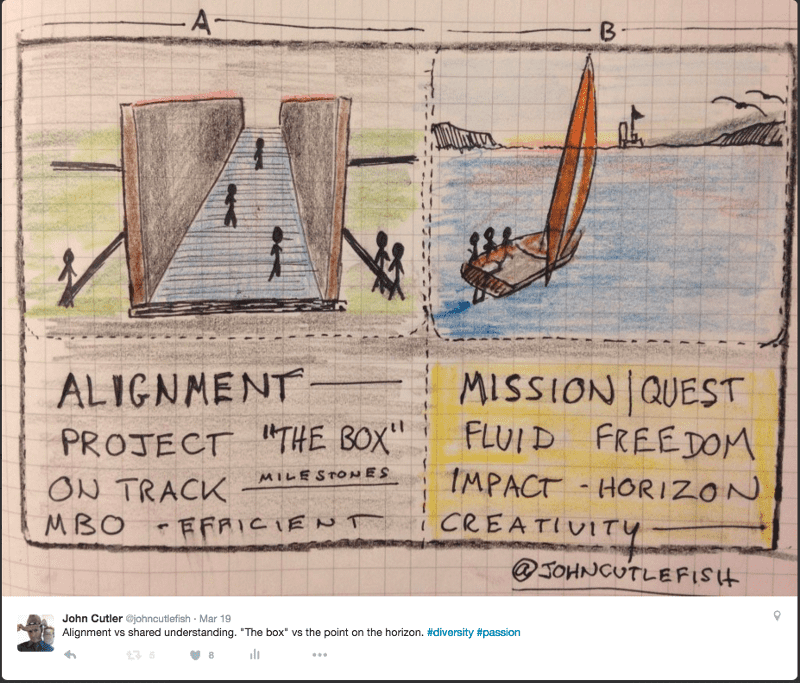

If Things Were Awesome

To be clear, I advocate for thinking in terms of initiatives, problems to solve, and missions. And that’s nothing new or groundbreaking. I use mind maps like this:

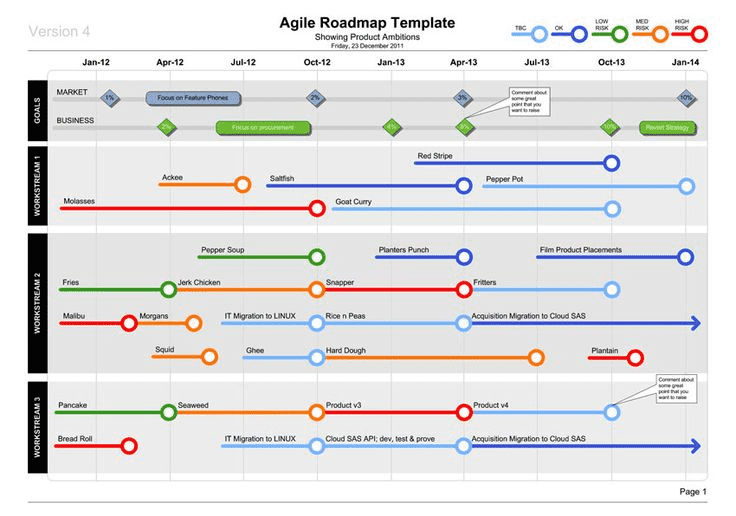

This advice is mirrored by most of the roadmapping software vendors like ProductPlan and Aha, as well as folks like Melissa Perri, Roman Pichler, etc. All caution against using the roadmap as a glorified feature gantt chart.

The other day, Woody Zuill asked me something to the effect of:

what would need to happen such that this wasn’t even an issue. What would it take for the company to be awesome?

Let’s try that thought experiment …

What would a crazy successful and awesome product development team actually look like? Would they still have gant-like visuals for their roadmap?

Probably not. The future might look nothing like a 12 lane LA highway. Because you’d be on a bullet train.

Needs & Being Awesome

Continuing on that thought …

- You’ve hired the roadmap because you have a Need

- If things were Awesome, what would things look like?

Need: “The process helps us have the right conversations”

Awesome: “We have the right conversations without needing a prop. It is easy to get real, and discuss priorities without solutioning. We leverage the right decision making and focusing tools for the job, without bad side-effects.”

Need: “I need to know if you’re working on my favorite feature, or plan to”

Awesome: “The product development team continuously surprises and delivers value. So much so that pet features become far less important. We maintain a low planning-inventory. All team members are encouraged to submit ideas to solve our most important challenges.”

Need: “We have to meet to decide which features are most important, to advocate for our ideas, and favorite features”

Awesome: “The problem to solve is known, and all team members — down to the developers, UX, etc. — are empowered to solve them and try to push the needle without drowning in meetings. And we make continuous progress towards those goals. Everyone trusts each other. When we fail, that’s OK as well … provided we learn, and do better next time.”

Need: “We need to have a yearly plan, and the roadmap is part of that”

Need: “We need to have a yearly plan, and the roadmap is part of that”

Awesome: “You always have focus, vision, and direction … not just in late December (or whenever your yearly planning period is). Gaining that shared understanding is a rapid process, and can happen at any appropriate time. Few dependencies hamper the team. We respond immediately to new opportunities, and data.”

Need: “We need to know what is coming down the pike!”

Need: “We need to know what is coming down the pike!”

Awesome: “The product is sellable, awesome, and valuable as is. You’d be able to sell to those people without pitching shaky future promises. You’d discuss features released in the last two months, and the prospect would be wowed. From a technology standpoint we can flexibly tackle new challenges without a ton of notice.”

Need: “We need to see the big picture, where are we going, and how our work fits into that”

Awesome: “The evidence of impact is everywhere: in customer feedback, in the data, and in the dollars and cents. Teams link their work directly to a compelling vision (the big picture). Most importantly, the current work is impactful, so there is no need to future sell internally.”

Note: If you listen carefully, most “big picture” discussions are actually a code for “we don’t think we’re making a difference”.

Awesome: “A steady stream of awesome. Short lead times are acceptable to partners, and the batches are small enough to handle gracefully. Teams iterate on features until they “hit the mark” and then marketing uses that actual data (and case studies and momentum) to market. Training and support coexist with the development teams instead of “tossing it over the wall”.”

Need: “The board keeps asking us for our roadmap”

Awesome: “The board knows what goals you are shooting for, and your progress towards those goals. Quarterly meetings involve real news, and real data, along with the sweeping vision (“we aim to take that hill, and that hill”). You’d exceed your goals, so no extra icing is necessary.”

No, no, no you’ll say. We need roadmaps to address these needs! But consider a time when your team was just flowing, building awesome stuff, making customers happy … was it because of your roadmap?

Conclusion

Roadmaps aren’t the problem, obviously. We pick our tools and methods. My goal with this post was to encourage you to challenge the “why”: why use roadmaps, why use roadmaps the way we typically use roadmaps, and what it might take to be awesome (such that this conversation is irrelevant).

Consider many of the enduring debates: estimates, roadmaps, technical debt, iteration length, team structure, roles, Agile …

Why do we continue arguing about them? Perhaps because they — and the methodologies we create to control them — are symptoms and medicine for those symptoms. Dig deeper!

The economic problem of (an organization) is rapid adaptation to changes in its particular circumstances. Then, the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources available to meet them. This problem cannot be solved by first communicating all this knowledge to a central board which then issues its orders. But the “man on the spot” cannot decide solely on the basis of his limited but intimate knowledge of his immediate surroundings . There still remains the problem of communicating to him suchfurther information as he needs to fit his decisions into the whole pattern of changes of the larger ( organizational) system

Friedrich Hayek, Nobel Laureate in Economics