…Even if you end up thoughtfully sprinting

OK. Your team has a choice…

- Here’s a prioritized list of stuff we need to tackle. Break down the work, and figure out what you can finish in the next two weeks. Let’s meet up in two weeks and reflect on where we are at.

- Here’s a prioritized list of stuff we need to tackle. Break down the work, pull from the top, and do your best. Let’s meet up in two weeks and reflect on where we are at.

Push-back to #2 typically involves variations of the following:

- In #1 the team will be motivated to make their sprint commitment.

- It is nice to have something to shoot for. #1 gives you that.

- Developers need to learn how to deliver on their promises. #1.

- #1 shows that the developers can deliver predictably.

- How can we possibly forecast this project without doing #1?

- With #1 we’d deliver a cohesive thing for feedback.

I would argue that #2 can deliver software products equally well.

- You want your team to do their best. Delivering a pre-determined set of stories is not a great measure of doing your best. For example, you might hit a big glob of refactoring. It’s hard. With #1 you’ll miss your commitment, but be doing your best.

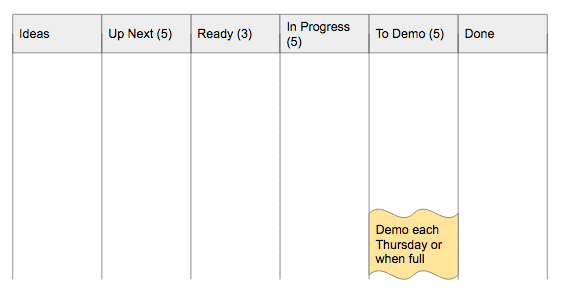

- #2 does not preclude having goals. But it does give you the flexibility to decouple goals of different types: feedback/learning cycles, delivery cycles, etc.

- Many teams are “basically doing #2, but with estimates and a sprint goal… we don’t treat the stories as a commitment”. Hmmm. Ok.

- There’s an easy way to consistently deliver on promises (especially in a low trust environment)… simply under-commit. We don’t want that.

- Predictability, almost by definition, requires time to pass. There’s no reason why #2 can’t demonstrate a predictable flow of done work over time.

- The ability to forecast is highly influenced by factors unrelated to the time it takes to actually “do” the work (e.g. batch size, work in progress, hand-offs, tooling, environment consistency, reviews, multi-tasking, utilization rates, etc.) Both #1 and #2 can address these factors, but #2 does so with less process overhead and abstraction.

So What?

My bias is clear. I like #2. However …

Here’s the important part. #1 and #2 are not all that different in terms of output/impact. Seriously, take a 30,000ft view. Are they?

I can picture a healthy team pursuing both with the exact same effect. Or for #1 to look more like #2 over time, and visa versa. If a team is empowered to continuously improve (and has the scope of influence to remove external blockers, and has psychological safety), they’ll find what is right for them.

The problem, in my mind, is that #1 — and all the rituals behind it (story point estimation, sprint “commitments”, burn-down/up charts, etc.)— are so easily abused. Let’s face it: they ARE being abused, ALL the time. The goal is not to DO SCRUM™ and dance all the little dances. Rather, it is to embrace continuous improvement and empirical process control (transparency, inspection, and adaptation).

There is nothing stopping your team reflecting on some cadence.

There is nothing stopping your team from setting meaningful goals.

So my advice is to stop sprinting, and to start thinking (even if you end up thoughtfully sprinting). Know the Why behind the various rituals. And make it safe to experiment and learn.