Nested hierarchies, boundaries, independence, and value…

Stories and Epics (and Independent Value)

- Story = a story that is small enough to fit into a sprint

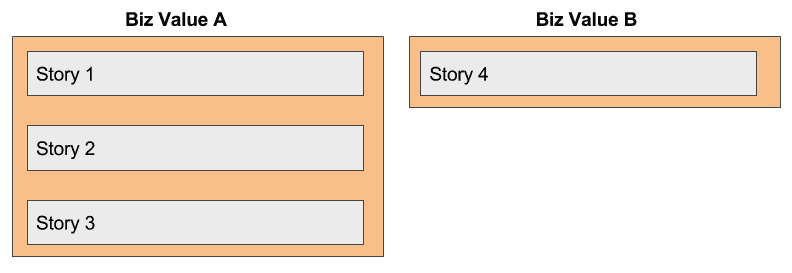

- Epic = a story that is too big to fit into a sprint In Scrum, Epics get broken down into Stories (because everything needs to fit into a sprint). Stories should be valuable and independent (see INVEST). And with that we arrive at an apparent contradiction: if the Story rolls up to an Epic, is the Story truly independent? And is the Story independently valuable? Maybe, but the value is locked:

While the stories that comprise an epic may be completed independently, their business value isn’t realized until the entire epic is complete.Hmmm. OK. So Story 1 below is not independently valuable from a “business” perspective (though may be extremely valuable from a learning standpoint, which is certainly valuable to the business). Story 4 is independently valuable from a business perspective.

Potentially Releasable

If you’ve done Scrum training, you may have gotten stuck on reconciling the use of Epics with the definition of a Sprint:

A time-box of one month or less during which a “Done”, useable, and potentially releasable product Increment is created.

The tricky phrase is “potentially releasable”. How can we have a potentially releasable product increment if some Stories are assigned to Epics, and Epics — by definition — are too big to fit into a Sprint?

There’s an answer for this puzzle too! Ken Rubin(author of Essential Scrum) contributed this nugget to Google Groups:

To be clear, “potentially shippable” does not mean that what got built must actually be shipped. Shipping is a business decision, which is frequently influenced by things such as “Do we have enough features or enough of a customer workflow to justify a customer deployment?” or “Can our customers absorb another change given that we just gave them a release two weeks ago?” Potentially shippable is better thought of as a state of confidence that what got built in the sprint is actually done, meaning that there isn’t materially important undone work (such as important testing or integration and so on) that needs to be completed before we can ship the results from the sprint, if shipping is our business desire.”In New Framework — the Increment, Ron Jeffries defines The Increment (which matches up with Ken Rubin’s description):

At regular intervals, preferably every week or two, the developers provide an integrated, running, tested version of the software, the “Increment”, containing all the features and capabilities which have been completed so far in the project. The Increment must be in usable condition and must meet all the agreed standards of completeness and correctness.Summary: Some amount of value has been delivered (even if that value is dependent on 1) other items being completed, 2) a function of the learning and feedback that is now possible, and/or 3) the sheer act of pulling “something” together that can be deployed). And in theory the work can be released.

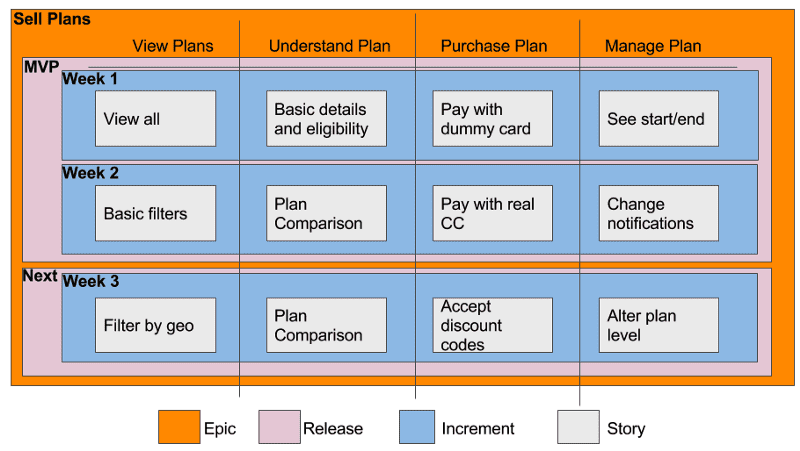

Story Map

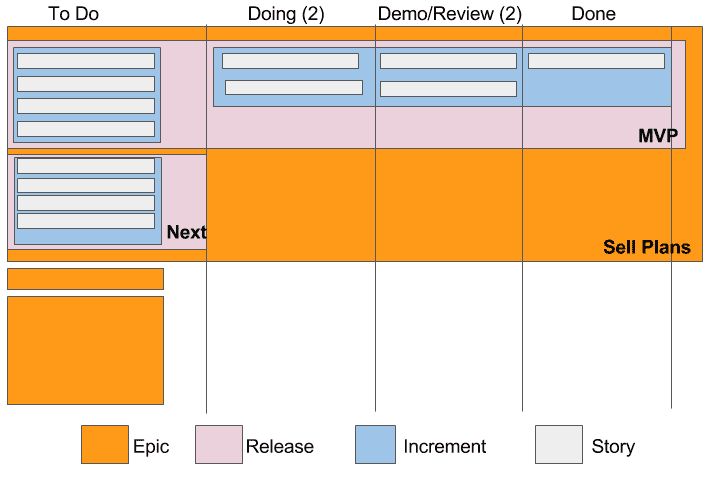

We decide it will be valuable to start selling subscription plans for our Widget Service. Here’s how Epics, Releases, Increments, and Stories might look using a User Story Map (see here for more info):

Note how these fit together:

- We create a horizontal flow based on the user journey

- We use Stories to focus our efforts on discreet bits of user-impacting functionality (feedback on these stories can be instantaneous and continuous)

- We use Increments to regularly inspect and adapt

- We use Releases to coordinate the decision to get something new in front of our users

- We use Epics as a container for business value (or at least an assumption around business value)

Incremental Inspect/Adapt

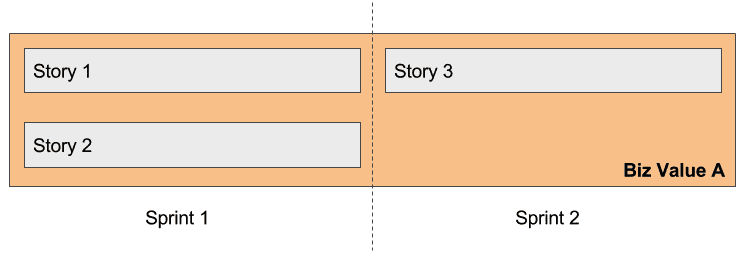

Grasping the value of The Increment, the team decides to do a weekly review. In a bout of experimentation, AcmeTeam drops their user story estimates, and strives instead to make user stories as “small as possible, but no smaller”. It’s like Scrum, but without worrying about a story point commitment/sprint planning. Grafted on to a Kanban board it looks a bit like this:

Not pretty (I prefer the Story Map)

Not pretty (I prefer the Story Map)

, but still helpful.

Every Thursday the team commits to reviewing “the features and capabilities which have been completed so far in the project” (see Demo/Review). Depending on the week, this demo should cover 2–4 Stories. Something is done and something is demoed. Now, it may not be the nice and neat Week 1 end-to-end increment as described in the story-map, but it is something. Instead of waiting until the end of next week — until it is all done — the team gets meaningful feedback.

But, the demo will only make sense if four stories are demoed together!Perhaps. Maybe the trick, then, is to schedule that demo the day those four stories are done?

So What?

Where am I going with all this? Consider that our original definition of an Epic was Sprint-constrained. But let’s remove Sprints from the equation.

At the end of the day, the central questions are:

- Can we break the problem down into smaller, discreet problems?

- What boundaries need to exist for the team to do its work? As PM, the boundary I might care about is end-to-end customer value. For a developer writing tests, something much more narrow is appropriate.

- How can we preserve the relationships (both hierarchal and adjacent)

- How do we make sure to align the work with user outcomes/benefits

- How do we inspect and adapt based on our progress?

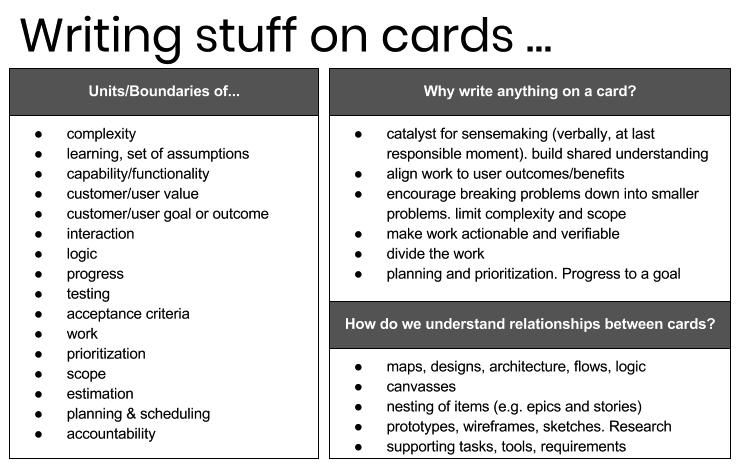

Less experienced teams tend to get tripped up trying to define Epics, User Stories, Task, and Sub Tasks. The reality is that software product development is typically one big nested hierarchy, and a super messy one at that. Additional tools — like maps, canvasses, designs, wireframes, logic diagrams — are needed to hold the mental model together.

Managers foist all kinds of meaning on to “cards” — as requirements, for scheduling, for accountability, to assign stuff to people, as units to measure velocity —while losing their essential connectedness (and squeezing out flexibility and customization for the task at hand).

You could probably do away with the words User Story and Epic altogether, and use these instead:

- Mountain

- Hill

- Boulder

- Rock

- Stone

- Pebble

- Grain I’m only partly joking.

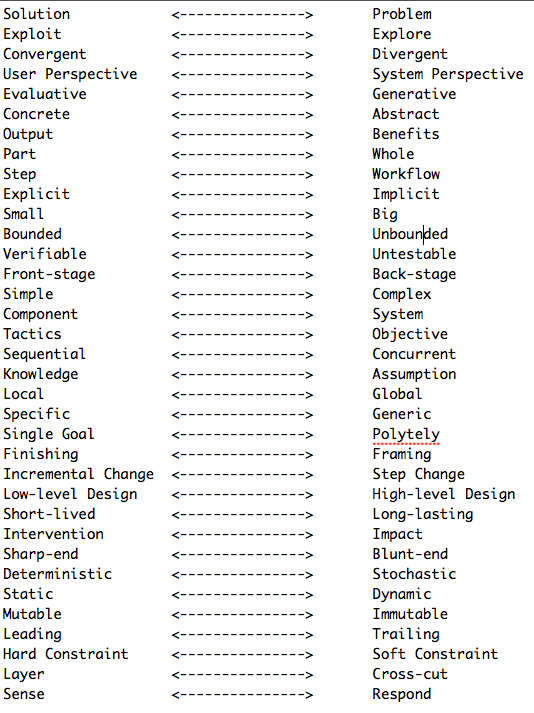

I’ll finish with a table that explains why it is so hard to settle on “standard” definitions for how we describe our work. Our work is all over the map below. Shared Understanding is hard. Great teams figure out how to keep their mental model accurate.