Why are you doing [some practice]?

Acme does it. It’s a best practice, right?Acme also does [some practice] and it looks promising. How about that?

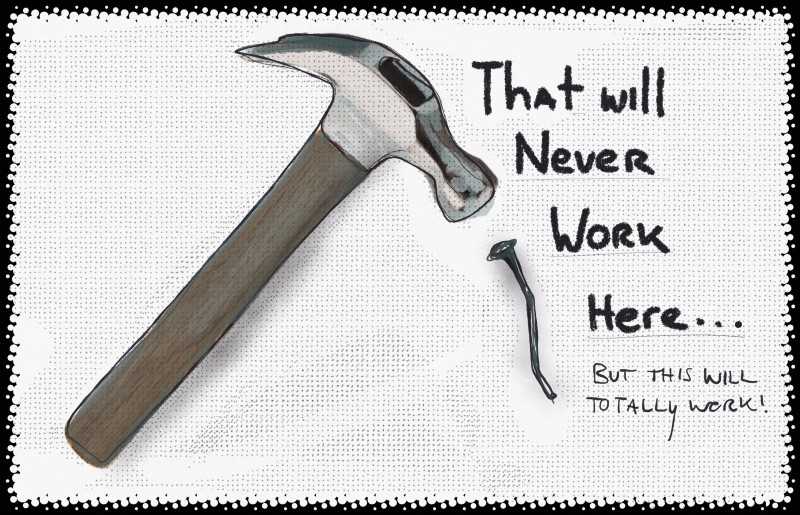

But we’re not Acme! We’re unique. That’ll never work here.I hear this kind of reasoning all the time. A classic example is OKRs. Companies adopt OKRs because they are considered to be a “best practice” at Company We Admire. Mention the autonomy/ownership teams enjoy at Company We Admire (or technical and managerial practices used to enable that autonomy), and you’ll get a monotone “but we’re not Company We Admire!”

OKRs are a good example because they “make sense” in a head-noddy kind of way. Alignment sounds awesome — and so do objectives and key results! OKRs feel reasonable and accessible. Now compare that reaction to how people typically react to practices like a “no bugs” policy, 10% time, embedding Ops, hiring a team of Agile coaches, trunk-based development, mobbing, pairing, team-based goals, dynamic re-teaming, and inviting customers/users into the development process. Big difference.

I’ve seen companies implement OKRs across the whole organization, but reject team-level attempts to experiment with something like mobbing, eliminating story points, or foregoing Jira. That’s right: a broad blast radius mandate vs. local safe-to-fail experiments…and big-bang wins!

Or adopt Scrum everywhere…but resist the “potentially releasable product increment” forcing function because it “doesn’t make sense here”.

On some level this is human nature. We generally make choices that are 1) non-threatening (to us at least), and 2) congruent with our worldview and prior experiences. We resist any suggestion that what we’re doing right now is less-than-optimal, but embrace “new stuff” that looks good on paper and doesn’t really disrupt the status quo. We hope the “new stuff” will fix the problems-that-aren’t-our-fault instead of actually changing how we behave/operate.

And then there’s the asymmetry of impact. Plenty of management practices “make perfect sense”, but only because the ripple effects are felt elsewhere. Local context can render these decisions downright toxic. Yet companies frequently fall into the trap of implementing “reasonable” centralized processes that have a net-negative effect (“why can’t the teams get with the program!”), while simultaneously discouraging local experimentation that feels risky (“oh no, what if that contagion spread…! We’d have the inmates running the asylum!”)

The net effect here is that companies adopt tons of generic practices that should be customized (but aren’t), and fail to experiment with specific practices that should be tried as-is even though they’re “difficult”. Basically… layers and layers of generic head-noddy, centralized, and non-customized processes, and a paucity of real experimentation and local variation. Since the generic practices are non-threatening, we find them beyond reproach (“oh come on, we can’t change our mind now…!”). While meanwhile, the threatening-and-risky-stuff-that-doesn’t-work-the-first-time gets quickly canned, or never gets tried in the first place.

It doesn’t matter if something works. What matters is the threat level it poses. We’re biased like that. All of us. We just feel threatened by different things. I frequently interact with people who are genuinely threatened by their company not adapting. They’re worried it will hurt their career. They’re threatened by boredom and risk-aversion. Their bosses are threatened by something else altogether.

So what to do? I think the key is making sure all process/tool experiments are viewed in an equal light. What are we hiring the tool/process to do? How can we make these experiments safe-to-fail? How can we prioritize more seemingly “risky” experiments? How do we jettison the things that aren’t working, and amplify the things that are bearing fruit? How do we shorten feedback loops and reduce the ripple effect? How do we actively challenge “legacy” decisions and/or customize them to be more applicable? How do we avoid slipping into the mediocrity trap by adopting lots of stuff that “makes sense”, but avoiding the real step changes in how we work?

There’s no silver bullet, but a great start is talking about this with your team. Consider experimenting with something like POPCORN Flow to make your continuous improvement efforts more transparent and outcome-based, and Modern Agile to put the focus on safety and “experiment and learn”.