The transition to more mission driven, autonomous teams is often characterized by an awkward period. Whereas before, teams were used to a prescriptive backlog of “things to do”, now it is very common to feel like you are in limbo.

Who decides what? Why aren’t people tapping away on keyboards? Is the work ready to be worked on? And what is the high level mission anyway? It is also normal to feel like you are drowning under a new form of process evil (that replaced the old forms of process evil).

In my days as a UX researcher, it was my job to coordinate two-week long kickoff and discovery “sprints”. The output of these sprints was typically a rough backlog of “stuff to build”, but perhaps more importantly a crystal clear understanding of the mission, assumptions, guardrails, success metrics, etc. We didn’t gloss over certainty. But we spoke of uncertainty with certainty (after doing the work of building shared understanding).

Much of the work was done away from keyboards and in conference rooms with the whole team (not a subset). Prior to these sprints I might meet with a senior PM, designer, and engineer to clarify the learning goals and state of the team, but for the most part the team was doing discovery together. They were doing the hard work together. Not all missions involved these discovery sprints — sometimes you know (or think you know) you need to build x,y, and z — and sometimes it took two days, not two weeks, but the overall idea was to build shared understanding.

An aside, as a facilitator I would budget 4hrs per team member of prep time for the activities…because good kickoffs and discovery predict initiative success by some crazy factor. It is almost criminal when they get short-changed because they are that important. When in doubt, I would bring in co-facilitators. And… even then, sometimes (often!) we hit the “end”, and realized it was just the beginning. A bias to action was important…but not a bias to premature convergence (different concepts).

In full disclosure, this would drive some people crazy. Leaders especially. It doesn’t look like “work” and feels lumbering. Makers thought it was superfluous. They just wanted to get going. It also cut to the real essence of autonomy. Autonomy for some people means implementing whatever solution they have in mind — that looks fun to work on. It also means not being “dragged down by other people” or “having to do lots of meetings”. There is another type of autonomy. And that type of autonomy involves being free to tackle a really challenging problem as a cross-functional team. Working as a team is messy. It means constantly revisiting what you understand together, and vacillating between “things are awesome” and “I’m not really sure what we are doing!”

If it drove people crazy, why did people put up with something that seemed so inefficient?

It worked. But it is hard.

To understand this better, let’s back up to before the push for more team autonomy. Part of the reason autonomy gets sapped from a system is the omnipresent pressure on product (and others) to get upstream and try to figure stuff out. They don’t do this to intentionally sap the autonomy of anyone…they’re actually doing this to help and because keeping people engaged and busy is rewarded by leadership. They are feeding the feature factory.

So when you start having more autonomous, mission-driven teams you get the backlash. Starting together is messy and involves a lot of ambiguity. It also takes TIME. Remember, there are many aspects of the system that are optimized for busy-ness, and you can’t just unravel that. In one org, we took kickoffs and discovery seriously. Everyone’s calendar got cleared. We went off-site if we needed to. In another, just scheduling it was impossible because everyone’s calendar was full, and because there was all sorts of side-work / reactive work invisibly sapping everyone’s time.

All those optimizations are inertia against truly starting together as a team. You have to respect the power of this inertia and actively fight it.

K&D can be messy. If it isn’t…are you just picking your first idea?

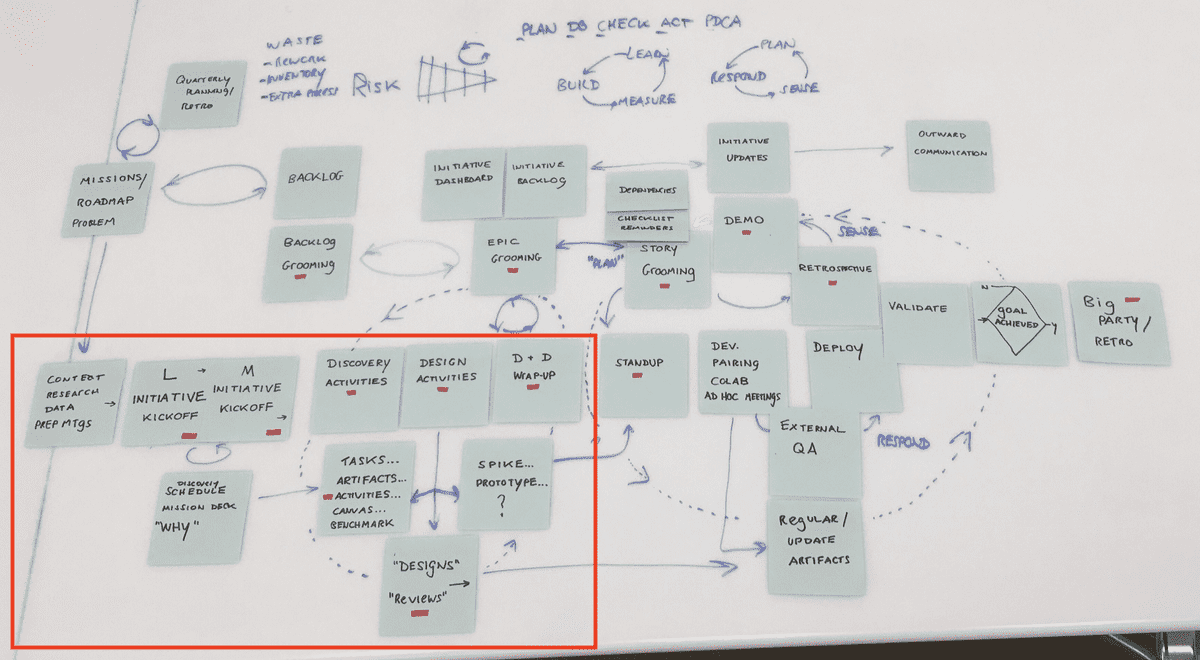

Kickoffs and discovery often follow the typical “double diamond” structure. They involve divergent exploration, convergent exploration, divergent “exploitation” (solutioning), and then convergent solutioning. There is a tendency to want to “just get started” but if you are framing the problem at the right resolution, you will typically notice some level of divergence. You know you are “doing it right” when there are three (or more) ways you could “solve the problem” (or capture the opportunity). Except, of course, if everything is known, plain-jane/joe, and you “just need to execute.’’ It is important to call this out when this is the case, but keep in mind that believing this to be true is a common intuition trap.

Ironically, after a number of repetitions of this kickoff/discovery approach you tended to see an eventual repudiation of “the process”. Why? Because the team — provided it was stable and/or had done it a million times — could be more fluid about what sensemaking to do when. The irony is that they just repeated the activities, but didn’t call it anything official. It just happened. This was almost never possible without repetitions of the loop. I’ve never met a product developer who instantly grokked discovery/exploration as a team and nailed it right away.

But when that pushback happened it was pure joy. The approach had become second nature.

OK, so where is this all going. What is the point:

- Starting together is very valuable (but counterintuitive)

- Kickoffs and discovery have a high influence on effort success

- K&D need love. They are messy. They will not seem efficient

- A bias to action is important, but probably delayed a bit later than you might do so intuitively (or later in the case of orgs with big upfront requirements gathering efforts). The team should design their own forcing function

- It is better to batch similar items under one compelling “mission” … you might find alternate solutions or paths. You’re at the right resolution when you can think of multiple potential solutions

- Resist the urge to get upstream (outside of framing context). Premature convergence is pesky.

- Hands off of keyboards feels inefficient, but engaging directly with customers, doing calls, looking at data together, story-mapping, assumption mapping, etc. is all very powerful

- Get everyone together in a room. Do the work. Rest assured, this is a muscle. You will get better.